Remembering Freeport’s own Tuskegee Institute hero

Editor’s note: This story was provided by the Freeport Historical Society.

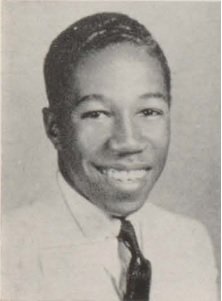

Freeport native Thurston Gaines looks friendly and unassuming in a photo that appeared in the 1940 edition of Voyageur, Freeport High School’s yearbook. Little would one know that he was destined for greatness as a Tuskegee Institute-trained fighter pilot who flew 26 missions for the U.S. Army Air Corps. Or that he would attend medical school and become a surgeon after an honorable discharge from the service in 1947.

Gaines died in December 2016, at age 94, a hero in the truest sense. He was buried at Riverside National Cemetery in Riverside, Calif.

Gaines was born on March 20, 1922, to Alberta and Thurston Gaines Sr. His mother raised him and his younger brother, Albert, in her parents’ family home on Lillian Avenue. He credited his mother with teaching him a strong work ethic, and said he appreciated the sacrifices she made as a single parent to raise her sons after their father left the family when Thurston was a young boy.

According to an interview that he gave to the Veterans History Project, Gaines was denied access to college preparatory courses in math and science. The principal of Freeport High at the time, Martin M. Mansperger, later helped Gaines obtain a scholarship to Howard University.

At Howard, he attended night school and took the math and science courses that he was unable to in high school. When World War II broke out, Gaines was in college and available for the draft. But he enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps in 1943.

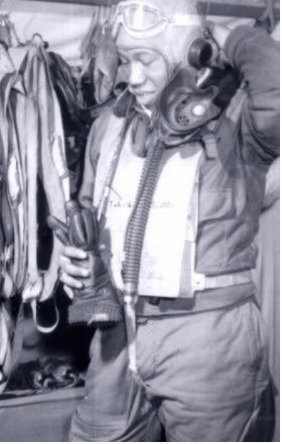

Gaines applied for pilot training classes held at the Tuskegee Institute. Initially, applicants had to be college graduates, but then the requirements were relaxed as the war carried on. The first time that Gaines took the admissions test he failed it, but was told to come back the next month and try again. He did so and passed it on the second try. Gaines graduated from the program in August 1944, becoming a flight officer. From Tuskegee, he went on to Waterboro, S.C.

While in the south, Gaines was subjected to racism and noted that many people he encountered were not interested in what he could do, but rather what he could not do. Becoming a fighter pilot was a way to fight discrimination for him.

In December 1944, he was sent to Europe on a Liberty Ship that embarked from Roanoke, Va., and docked in Marseilles, France. From there, he was assigned to the 99th Fighter Squadron, 332nd Fighter Group, which was stationed out of Ramitelli Air Base in Italy on the Adriatic Sea.

On April 15, 1945, Gaines was assigned to carry out a strafing mission over Munich, in the southern part of Germany. In what was his 26th mission, while flying his P-51 Mustang fighter plane nicknamed the “Jupe,” Gaines was hit by enemy antiaircraft fire roughly a mile outside of Erding, Germany.

Gaines tried to keep the plane in the air to reach Allied lines, but the cockpit filled with smoke and the rudders were damaged, so he could not steer and the plane lost altitude. Finally, the plane broke up from the damage caused by the antiaircraft fire. Gaines was forced to eject, and he parachuted behind German lines about 40 miles outside of Muhldorf, Germany.

He injured his back, a shoulder and his teeth when he hit the ground. Once he got to his feet and gathered his parachute into a bundle, he looked for a place to hide. A group of teenagers were in the woods where he came down and motioned to him that he should hide in the bushes, which he did.

German troops soon arrived, and the teenagers gave up Gaines. Within days, he was sent to Stalag Luft VII in Moosburg, Germany, as a prisoner of war.

The stalag, or prison camp, held roughly 25,000 allied prisoners of war, about 8,000 of whom were flight officers. Because of the American Red Cross, the prisoners were fed. According to Gaines, the German soldiers running the camp gave prisoners one meal in the month that he was imprisoned, which he noted was made from dishwater. Gaines and the other prisoners of war were freed in June 1945 by the 14th Armored Division led by Gen. George Patton.

For his service, Gaines was awarded the Air Medal with Two Oak Leaf Clusters, a Presidential Unit Citation and the Purple Heart. In 2007, as a belated thank-you to the pilots trained in the Tuskegee Institute and their service for the U.S. military, Gaines and the surviving members of Tuskegee Airmen were awarded the Congressional Gold Medal by President George W. Bush.

After arriving back in the U.S., Gaines returned to the Tuskegee Institute to train future pilots to fly the B-25 bomber, and he was promoted to second lieutenant. Upon leaving the military in 1947, he enrolled in New York University and graduated the following year and later earned his doctorate in medicine at Meharry Medical College in 1953. He earned his board certification in surgery in 1959 and worked first as a medical examiner in Meadowbrook Hospital (now Nassau University Medical Center) before going into hospital administration as a medical director at a veterans hospital in Massachusetts.

While working at Meadowbrook Hospital in the mid-1950s, a high school friend, who lived in Levittown, was selling his home. Gaines and his wife went to visit and have dinner with the friend one evening and expressed an interest in purchasing the house. The classmate agreed to sell the home to them. Before the closing, homeowners in the area found out about the prospective sale and were unhappy about the prospect of a black family moving in. They pooled their money and offered a higher price to counteract Gaines’s offer. However, the classmate did not accept the neighbors’ offer and sold the home to the Gaines family. He and his family lived in their Levittown home from 1955 to 1961, at which time they sold their house and moved to Rockville Centre.

Gaines tried retirement in 1988, but a decade later returned to work, first as a phlebotomist and then as a professor of naturopathic medicine at Southwest College in Arizona. He also substitute-taught at a junior high school.

While growing up in Freeport, he met a young girl named Jacqueline Kelly. He married her while he was in the Primary Cadet Corps. Their marriage lasted 71 years and the couple had three children: a daughter and two sons.

Denise Ruston is a trustee with the Freeport Historical Society and a member of the Freeport Landmarks Preservation Commission.

49.0°,

Fair

49.0°,

Fair