Company to appeal Glen Cove council's 'no' vote on group home

City faces uphill legal battle on Padavan law

Monte Nido — the company behind a proposal to open a group home for women with eating disorders at 1 St. Andrews Lane in Glen Cove — submitted an application last weekend to appeal the city’s rejection of the plan.

“We have filed our objections, and we have requested a hearing,” said Jennifer Gallagher, Monte Nido’s chief development officer. “It should take between two and three months to schedule.”

At that point, the city will present its case to an official from the state’s Office of Mental Health.

Monte Nido’s proposal was made under the Padavan law, a state mental hygiene statute designed to make it difficult for municipalities to say no to group homes. The law gives municipalities two options for objecting to such a proposal: They must either suggest alternate properties for the proposed facility — which the applicant is under no obligation to take — or demonstrate that there are already so many similar facilities in the area that an additional one would “substantially alter . . . the nature and character of the areas” around it.

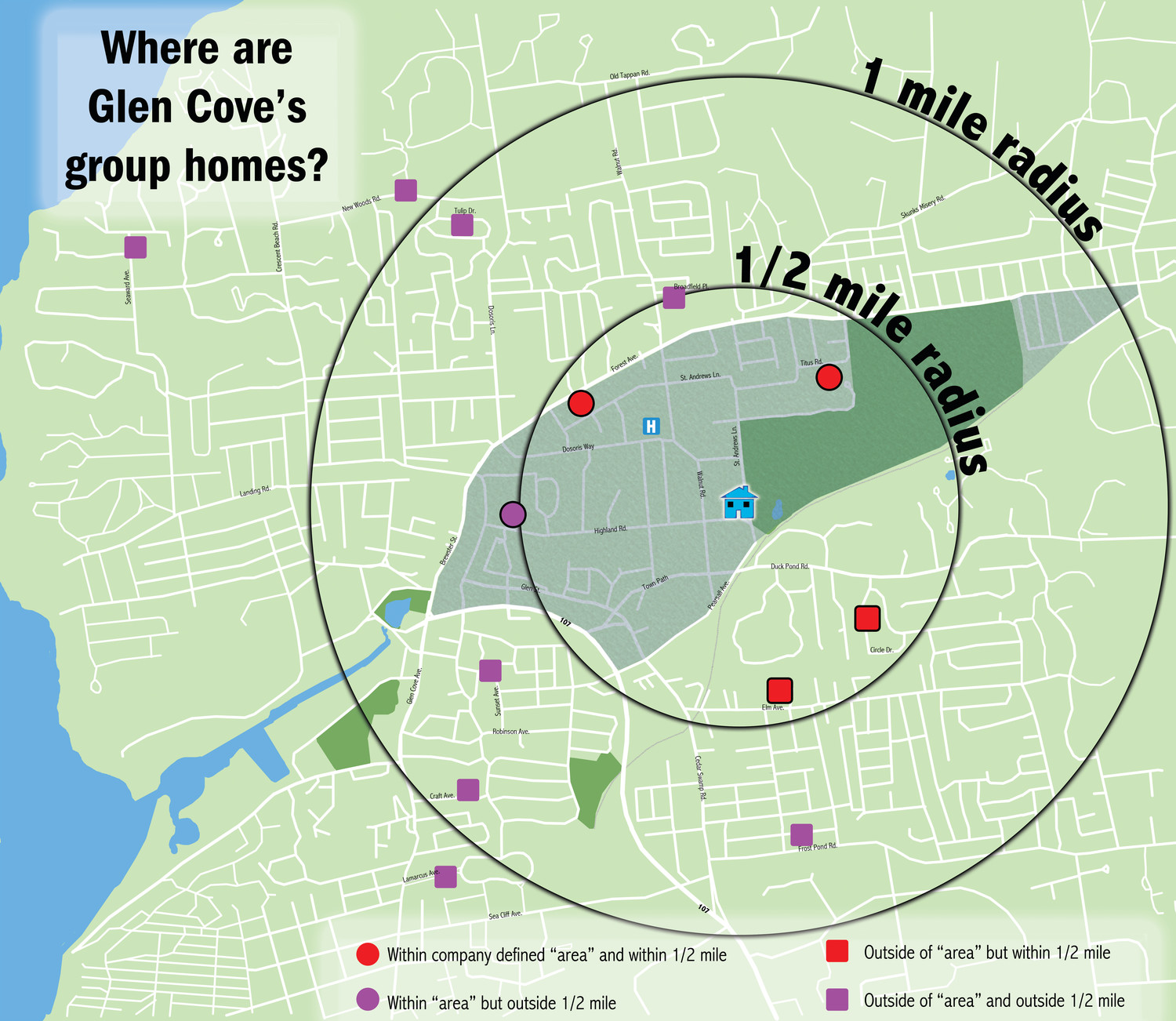

There are 13 state licensed group homes in Glen Cove. Six are owned by AHRC, a company that provides services to people with developmental disabilities; two are run by the Melillo Center for Mental Health, a nonprofit that focuses on psychiatric disabilities and substance abuse; and the remaining five are owned by organizations that focus on either mental health or the developmentally disabled.

If it is to prevail in the appeal, the city must show that a high concentration of group homes would significantly impact that character of the neighborhood. Part of the legal discussion centers on the best way to define a “neighborhood.”

At a public hearing last month, Monte Nido used main thoroughfares as borders to define the neighborhood surrounding 1 St. Andrews Lane. Gallagher said that the company’s definition was based on “what was considered accessible by foot for the [residents of our proposed facility]. Our attorney lives in the area, so she was instrumental in helping us understand” the boundaries of the neighborhood.

Others at the hearing suggested that a radius around 1 St. Andrews ranging from a half-mile to a mile be used to define the neighborhood.

In a 1997 case that appears to be the most frequently cited Padavan-related lawsuit, then Chief Judge Judith Kaye, with the unanimous support of her five colleagues on the New York State Court of Appeals, came down on the side of “boundaries created by parks and main thoroughfares which residents were not likely to cross on foot.”

The city’s rejection of Monte Nido’s proposal, a resolution passed unanimously on Feb. 20, listed three other properties — one on Dosoris Lane, one on Walnut Road and one on Crescent Street — and also argued that opening a group home on St. Andrews Lane would change the neighborhood too much.

In response, Gallagher said that the choice of the St. Andrews house was not made lightly. “We spent months looking for a property that would meet the requirements of the program,” she said, “and that would be respectful of the neighbors.”

Gallagher added that none of the city’s suggested alternatives has enough floor space to meet the company’s requirements — at least 6,000 square feet, for 14 residents and a handful of staff.

“I appreciate that they’re trying to be helpful,” she said, adding that Monte Nido was already “under a binding contract to purchase 1 St. Andrews” and that the company was willing to fight for that property.

According to James Plastiras, a spokesman for the Office of Mental Health, the only way for the city’s objection to be sustained would be if it could prove that there are already too many group homes in the area, and that the addition of a new one would change the nature of the neighborhood. Gallagher said that, as far as she knows, no other municipality that has tried to reject a group home under Padavan had been able to do so. “We have not found any decision that’s been made supporting a municipality’s objection,” she said, adding, “Whether it’s the OMH or the OPDD” — the Office of People with Developmental Disabilities, another agency that makes use of the Padavan law — “neither of them have supported a negative decision.”

Plastiras said he would try to confirm that claim with a “Padavan expert” from among OMH’s lawyers, but did not do so before press time.

Gallagher said that she hadn’t heard any arguments by the city that proved its case. “We don’t believe that the city provided any evidence,” she said, adding that while officials objected, “They didn’t give any reasons why.”

49.0°,

Fog/Mist

49.0°,

Fog/Mist