Hempstead Ave. subdivision held up amid debate of proposed ‘public street’

Case drags on as Board of Appeals consider distinction between public and private road

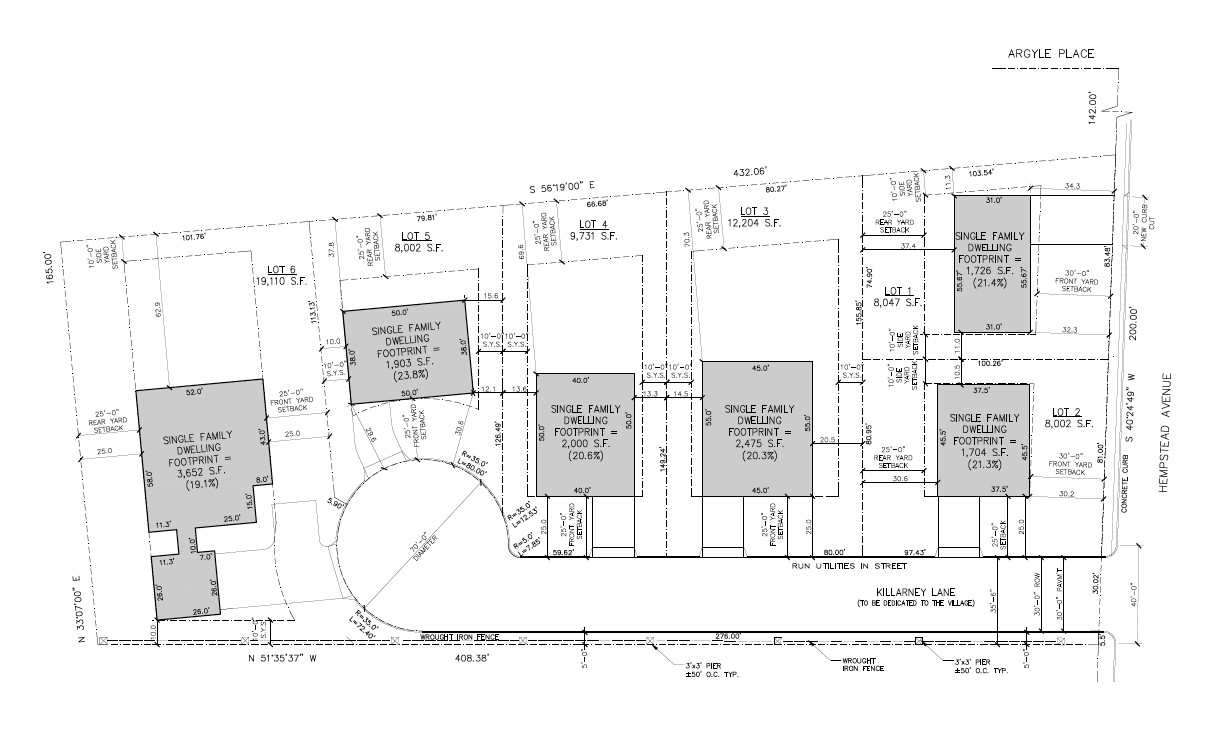

A plan to subdivide a 1.75-acre plot on Hempstead Avenue, adjacent to St. Mark’s United Methodist Church, into six single-family properties has been held up again, as the Rockville Centre Board of Appeals mulls whether the proposed road that would run through the property would be considered public.

The owners, Jim and Brett O’Reilly, who live in the house that once served as the church’s parsonage, plan to demolish it and build six homes on the site. Their original plan called for constructing four homes, which had attracted opposition from some residents over the past year. The Board of Appeals denied a zoning variance for that plan in June.

As in the previous proposal, a new street, to be called Killarney Lane, would be built perpendicular to Hempstead Avenue, to allow access to the homes planned for the back of the property. But the village’s Building Department denied the O’Reillys’ most recent application last month, according to John A. Matthews, counsel to the Board of Appeals, because it did not consider Killarney Lane a public street.

If Killarney Lane was deemed a private street, four homes in the proposed subdivision would not meet zoning requirements, because single-family homes must have 80 feet of frontage along a public road. The Board of Appeals heard the O’Reillys’ case at its meeting on March 28 to rule on the village Building Department’s interpretation.

Chris Browne, an attorney representing the O’Reillys, said that the road — a cul-de-sac — would be available to the public, and would be dedicated to the village. “Since we are proposing a public street . . . in the end, I don’t think there’s really anything for this board to decide,” he said.

“I understand your position, but I disagree with it,” Matthews told Browne, noting that the term “public street” is not specifically defined in the village code. “I think the fact that you don’t have a road that exists puts you in a completely different arena.”

The village passed a local law in 2016 that amended a section of the village code to clarify “street,” in connection with zoning matters, to mean a public street. Matthews noted that before that law was passed, this case would have already moved on to the planning board.

Village Attorney A. Thomas Levin wrote to the Herald in an email that the law was passed after several board members expressed that private roads — of which there are currently none in the village — “are not desirable because they cause problems of various kinds, including maintenance, utility service, garbage collection, snow removal and traffic regulation.”

Robert Schenone, chairman of the Board of Appeals, said he believed the law was also passed to prevent homes from simply fronting what he called a “flag lot,” which he said essentially acts as an extended driveway. But Browne said that Killarney Lane would be built as any other road in the village, and could be traversed by anyone.

The meeting was just the latest setback for the O’Reillys’ plans, which have been delayed several times over the past two years. Last July, the village’s Board of Trustees voted to institute a six-month moratorium on construction on properties that front private roads or do not have the minimum frontage on public roads. Browne had called the building freeze “a political attack” on his clients’ property rights, and in October, Nassau County Supreme Court Judge John Galasso nullified the moratorium in part because it targeted the O’Reillys’ application.

“The decision on whether to improve the subdivision, which includes the creation of the new proposed public street, rests entirely with the village planning board,” Browne said, noting that the new six-home plan is zoning compliant. “This application has never made it to the planning board.”

Residents have expressed opposition to the subdivision at previous meetings, citing the former parsonage’s historical value, as well as overcrowding and the destruction of open space. The Mayor’s Task Force on Historic Preservation was formed partly in response to the subdivision plan at 220 Hempstead Ave., according to some of the group’s members.

“There is no road there, and thus this is all conjecture and it is conditional,” resident Michael Mulhall said of the application. He noted other large open properties in the village, and warned that allowing a developer to build a road that is considered to be public would set a dangerous precedent. “This may fit this one situation,” he added, “but it may hurt us in the future.”

Matthews and Browne discussed the possibility of a conditional acceptance by the Board of Appeals. In that case, if the planning board did not approve the subdivision or the village did not accept Killarney Lane as public, the O’Reillys would have to return to the Board of Appeals and ask for a variance, since four homes would not be fronting a public road.

“I think making a conditional approval would just circumvent the whole purpose of the new definition,” said resident Jennifer Santos, chairwoman of the Mayor’s Task Force on Historic Preservation, referring to the village’s 2016 law.

Schenone said the case would continue to be heard on April 18, to allow for more public input. He added that it was a legal issue he wanted to give more consideration.

“We can’t create the road unless the planning board approves the creation of the road,” Browne told the board, “and without that approval, the road can’t be a public road. It becomes sort of around and around in a circle.”