Long Beach City Council learns details of confidential separation agreement

Former city manager's payout deal with corporation counsel was scrutinized in state's draft audit

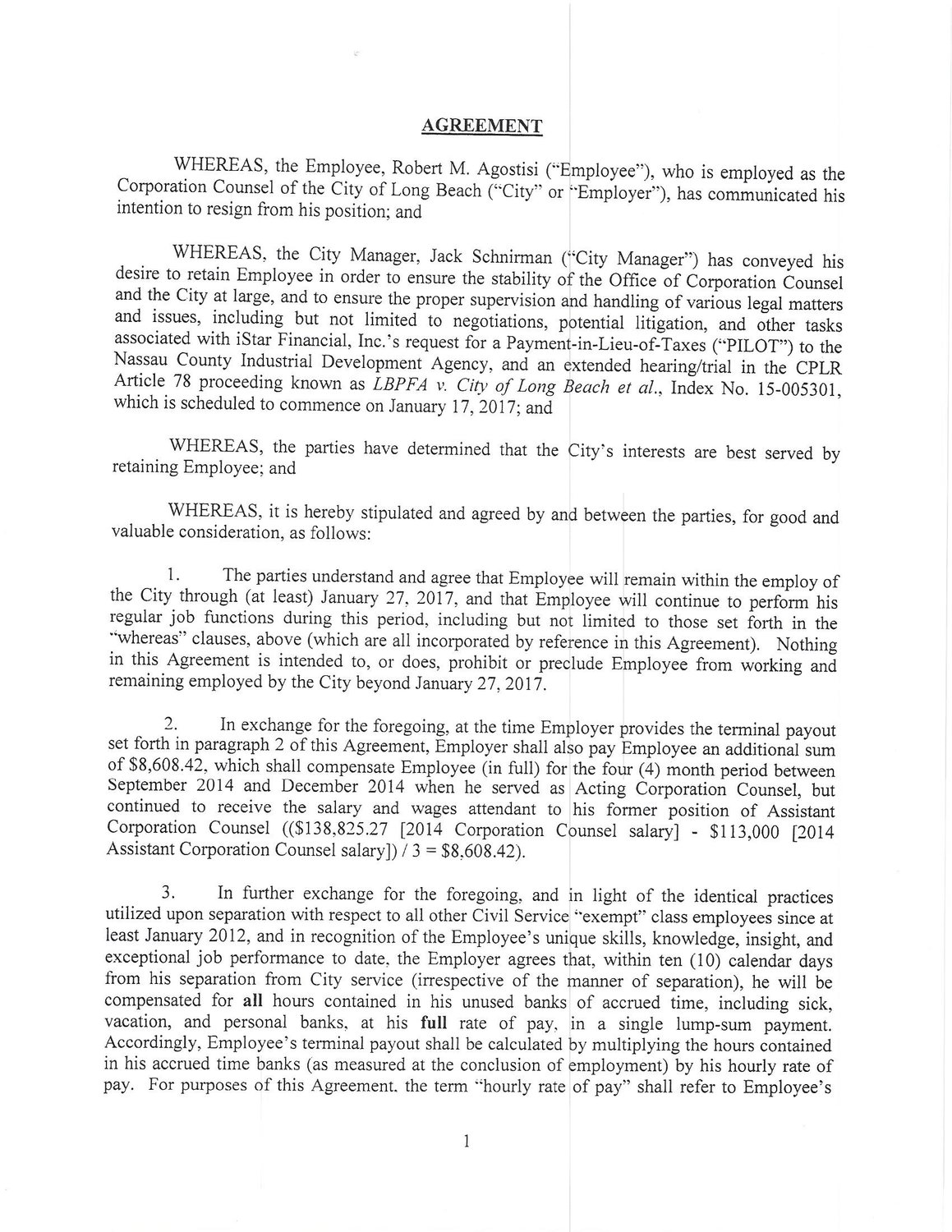

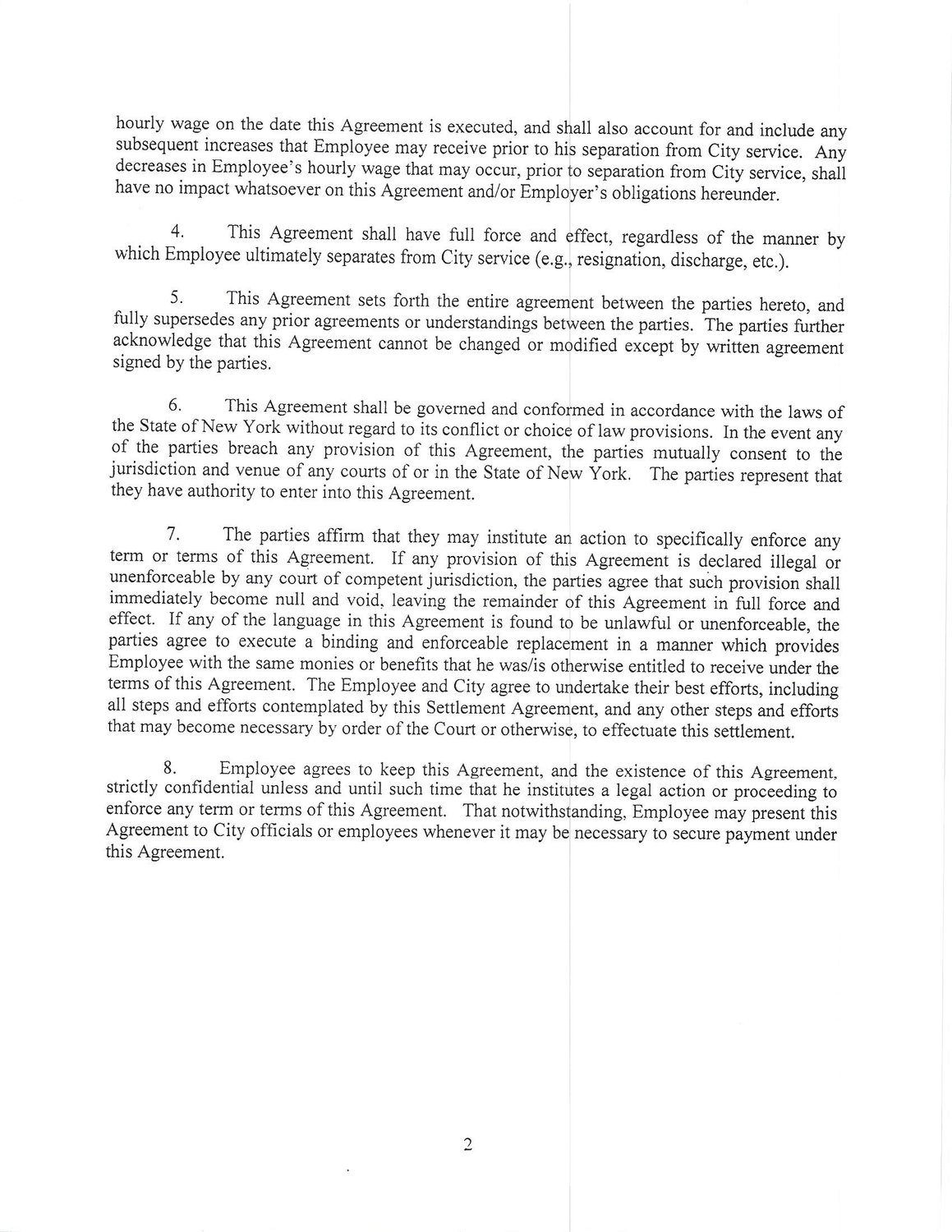

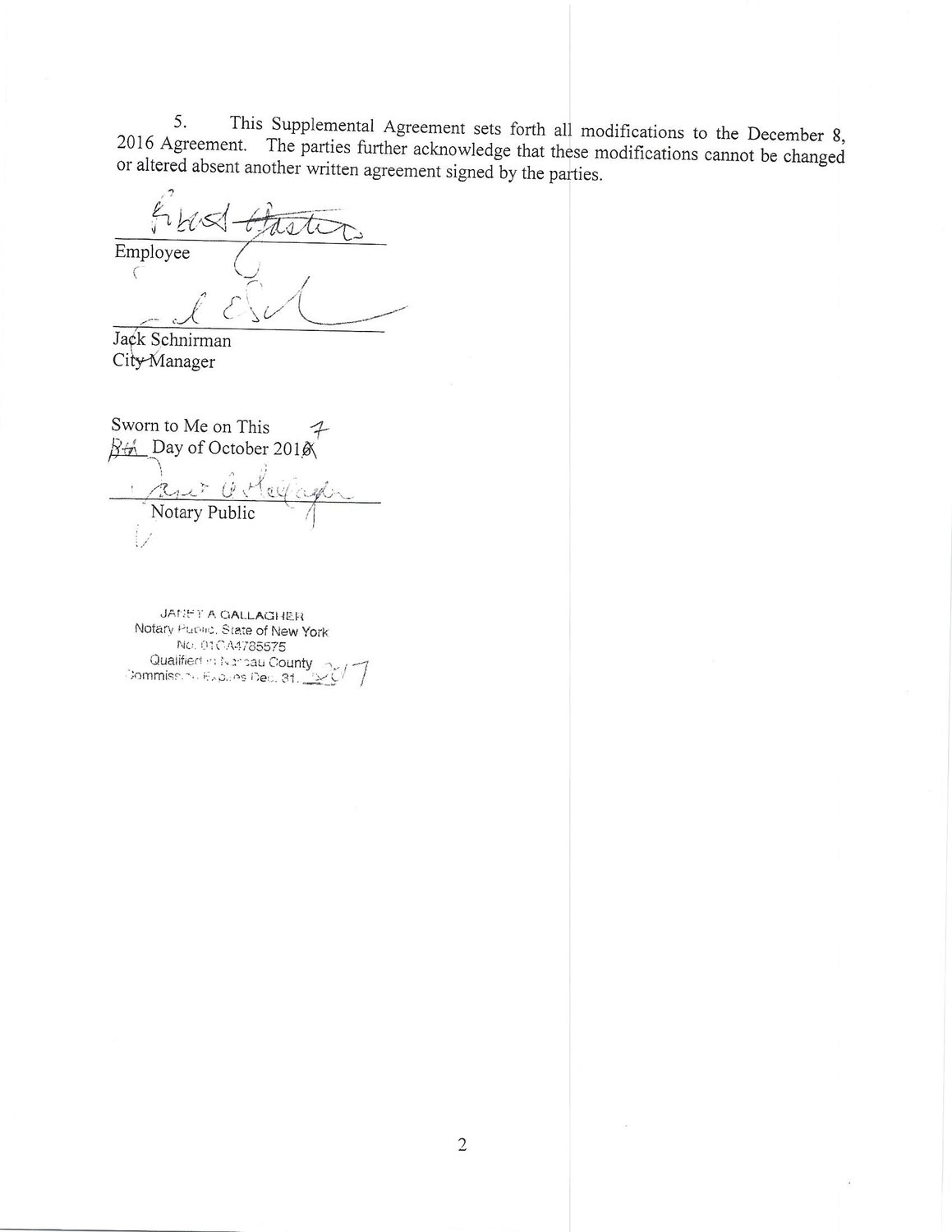

Former Long Beach City Manager Jack Schnirman approved a confidential agreement with Corporation Counsel Rob Agostisi in late 2016 that would compensate Agostisi for all of his accrued time when he left the city’s employ. The details of the deal were not disclosed to the City Council until last week.

The separation contract, obtained by the Herald, was entered into by Schnirman — now the Nassau County comptroller — in December 2016 to retain Agostisi after he had informed the city of his intention to resign.

The terms of the deal stipulated that Agostisi — who was appointed acting city manager in January — keep the agreement “strictly” confidential, but could present it to city officials and employees “whenever it may be necessary to secure payment.”

The agreement allowed Agostisi, who has worked for the city for 13 years, to collect all of his accrued sick, vacation and personal time, even though the city’s Code of Ordinances states that non-union employees like Schnirman and Agostisi are entitled to 30 percent of total accrued sick days when they leave the city’s employ, and can claim up to 50 vacation days. Agostisi received a $128,000 payout in the fall of 2017 because he had intended to leave for a job at the Town of Hempstead, and attempted to return the payment when he decided to continue working for the city, but was told he could not.

The agreement, which some council members said they were unaware of until last year, raises questions about Schnirman’s involvement in how his and other payouts were calculated, after a draft audit from the state comptroller’s office found, among other issues, that the city had overpaid 10 current and former employees more than $500,000 in separation payouts in the 2017-18 fiscal year — including Schnirman, who was overpaid by more than $50,000. The draft audit also stated that city payouts have exceeded limits set in city code and contracts for at least 25 years.

Earlier this month, Schnirman returned the $52,000 overage to the city, saying that he agreed with the audit’s findings. Agostisi resigned, effective at the end of the month.

“I am aware of the recommendations in the state comptroller’s draft audit, and in short, I agree,” Schirman said in a statement to the Herald. “I now understand that the methods Long Beach has been using to calculate payout amounts for at least the last 25 years are different than the stricter formula originally set out in the City Code. What the state comptroller’s draft audit tells us is that the City of Long Beach has paid many types of employees more than necessary for separation pay for at least 25 years, including myself.”

Schnirman did not immediately return a request for comment on the disclosure of his agreement with Agostisi.

Schnirman, who was appointed city manager in 2012 after Long Beach Democrats regained control of City Hall, said last month that he had submitted his time sheets to the city’s payroll department and that he did not calculate or process his own payment “because that would be inappropriate.” He has long maintained that he acted on the advice of a previous corporation counsel based on a legal interpretation of the code. He did not sign his separation agreement when he left the city. Schnirman was paid for all of his accrued sick and vacation time when he received a $108,000 payout after he left the city to serve as county comptroller in January 2018, even though the code and his employment contract with the city specified that he be paid 30 percent of his sick hours. He also received $34,910 for 419 unused vacation hours, more than the 50-day cap.

But the agreement Schnirman signed with Agostisi specifically authorized Agostisi to collect his accrued sick, vacation and personal time at his full rate of pay, “in light of identical practices utilized upon separation with respect to all other civil service ‘exempt’ class employees since at least January 2012.”

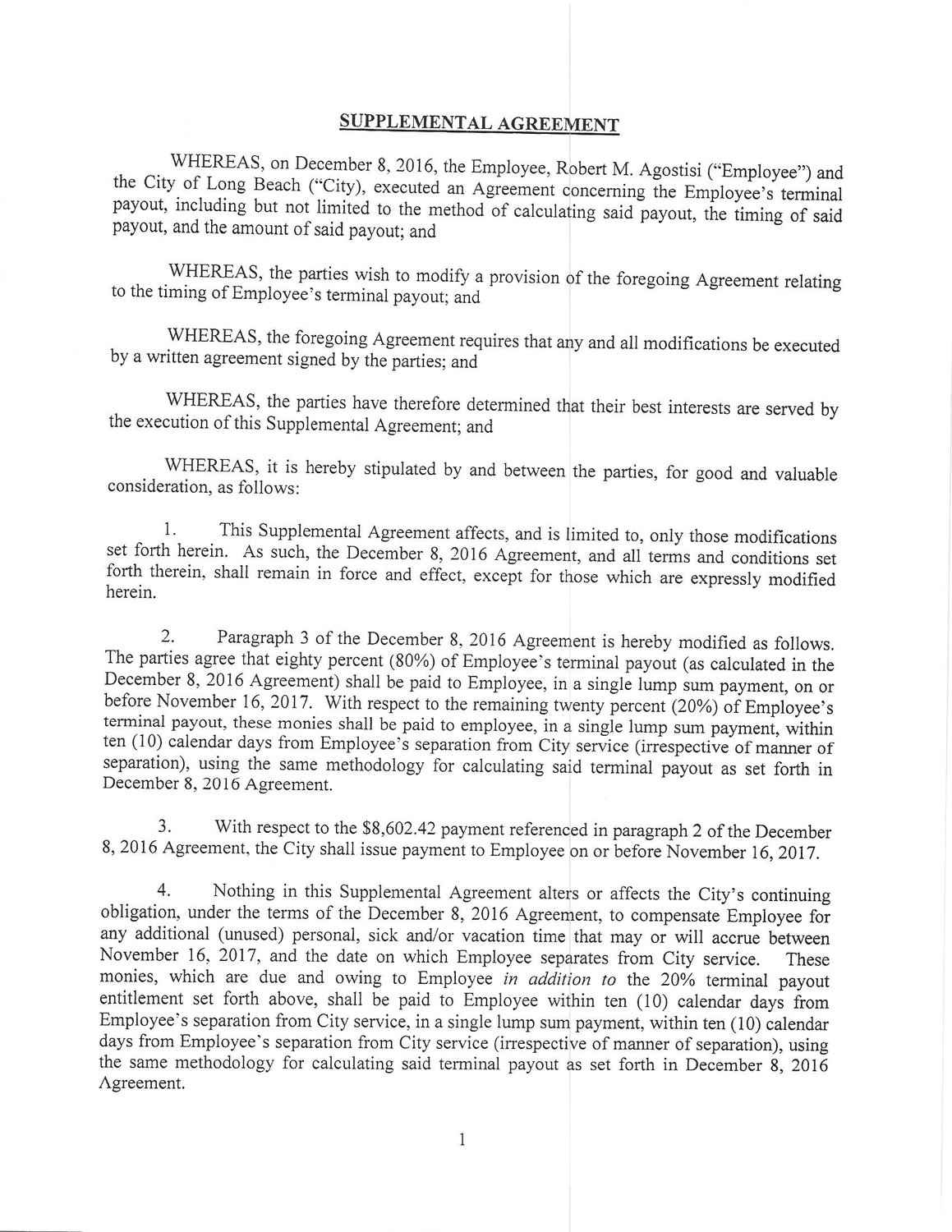

According to the terms of the agreement, Agostisi, who was appointed corporation counsel in 2014 and received an annual salary of $138,000, agreed to stay on as counsel through at least January 2017, at which point he would receive a lump sum payment upon his departure. The deal was amended in October 2017, however, to stipulate that Agostisi would receive 80 percent of his separation payment in a single lump sum on or before Nov. 16, 2017, and the remaining 20 percent within 10 days of his separation from service.

Former council President Anthony Eramo and other city officials have long said that retaining Agostisi was crucial, citing his institutional knowledge of the city.

According to the agreement, Schnirman lauded Agostisi’s “exceptional” job performance and stated his desire to keep him to ensure the “stability” of the corporation counsel’s office and ongoing legal matters, including negotiations — and potential litigation — with the developer iStar over the Superblock project.

In the draft audit, however, Agostisi’s agreement came under scrutiny. Under city code, auditors said that Agostisi’s drawdown of accrued time should have been limited to 40 hours, or $2,918. The auditors also questioned whether the city could enter into the agreement to provide a “terminal payout” that appeared inconsistent with the city’s code for exempt employees. Agostisi is still owed for additional accrued sick and vacation time since 2018, but council members have said it was not yet clear how much he would be paid.

Agostisi declined to comment. City Council Vice President John Bendo maintains that Schnirman did not have the authority to enter into such a contract with Agostisi, citing the city’s charter and code. Unlike Schnirman’s employment contract, the council did not approve the deal with Agostisi. Other council members did not respond to requests for comment.

“The only employee that can have a contract is the city manager, and that has to be approved by the City Council,” Bendo said. “It should be noted that both of these individuals received payouts that are currently being investigated by the authorities.”

The city, however, referred to a section of its charter that states that the city manager is permitted to sign, on behalf of the city, all contracts made by it, and Schnirman has entered into other agreements without council approval. The agreement with Agostisi pertained only to his separation from service.

Three City Council members had intended to hold a special meeting on Sept. 10, in part to force Agostisi to release the agreement. Some council members and residents had called on him to disclose it for almost a year, at meetings and through Freedom of Information Law requests. Some residents said they were told their FOIL requests were denied because the document could not be found.

According to emails obtained by the Herald, last November, Agostisi said he was willing to show Bendo a personal copy of the agreement he had, but only if former Acting City Manager Mike Tangney were present as well. Bendo refused, saying that was unacceptable.

Agostisi provided the council with the document hours before he offered his resignation last wee — he is leaving to serve as chief legal officer for the LGBT Network next month — and declined to comment on his departure.

44.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

44.0°,

Mostly Cloudy