Local father tells students his famous life story

Geoffrey Canada, Sr. advocates non-violence, respect

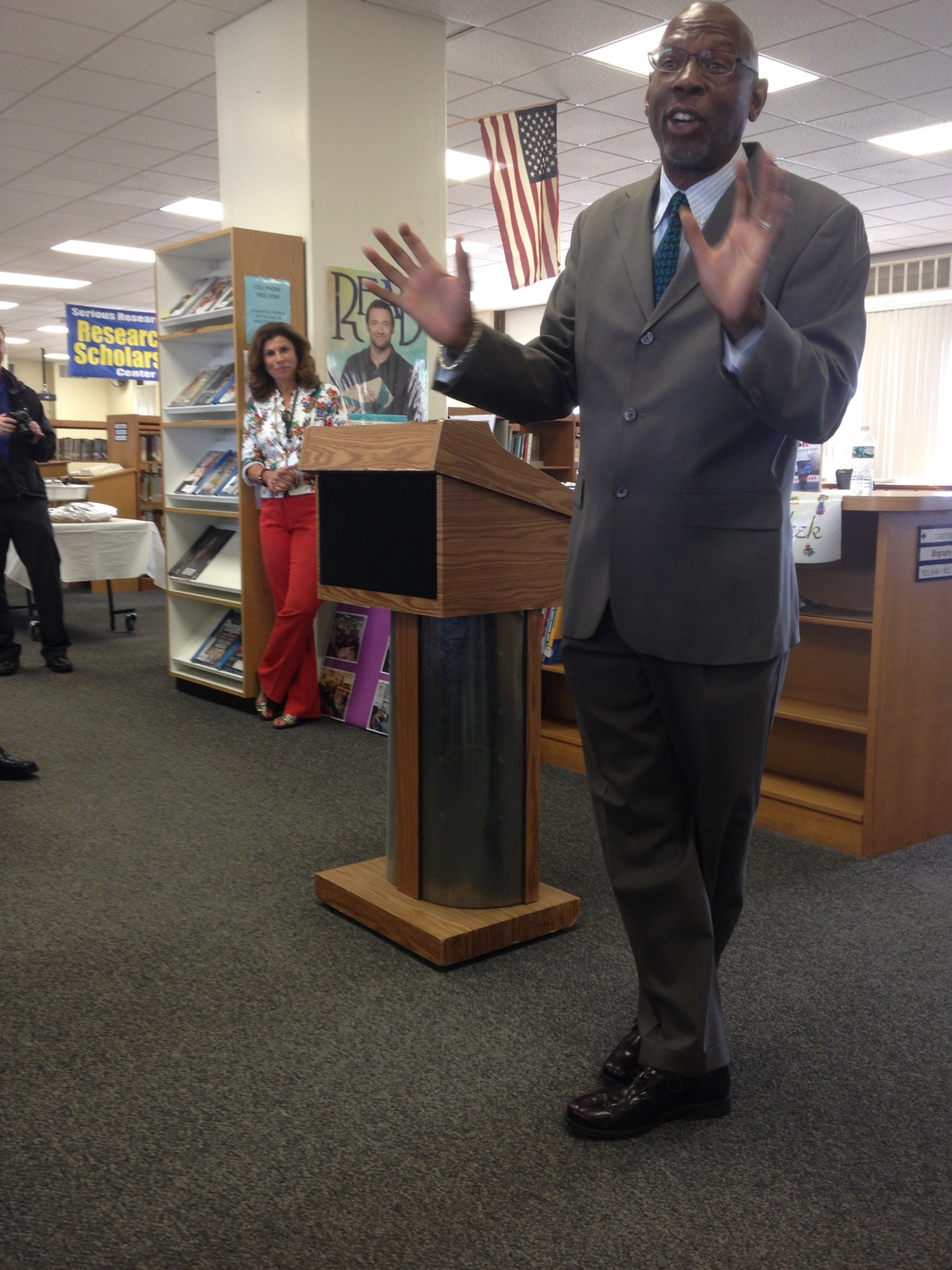

Geoffrey Canada, Sr., the world-renowned educator and local father who runs the Harlem Children’s Zone, spoke at Central High School for the school library’s Bring a Book to Life event on April 15, telling students to be aware of their choices in the context of a society that he’s witnessed become increasingly violent since his trials as a young man growing up in the Bronx.

“Here’s some things that you should know,” said Canada, who presented “Fist Stick Knife Gun: A Personal History of Violence,” his 1995 autobiography. “In our country, if you are a young person, the chances you are going to be murdered are higher than any other place on the face of the earth. And if you’re an African-American male, the number one cause of death for teenagers is homicide.

“Now, that may not strike you as a big deal here in Valley Stream, because last I looked, there weren’t a lot of kids being shot here. But in lots of places, young people are being killed. So if you want to understand why I thought this was important to write, you need to understand some numbers.”

Canada recited annual average rates of murder by firearms from other countries: less than 50 in Japan, around 150 for European countries and about 200 in Canada. In the U.S.: 30,000.

“There is an epidemic going on of Americans killing other Americans using handguns,” he said.

A large part of his life, he said, has been his attempt to understand violence and how people think about it.

Canada grew up in the Bronx in the 1960’s, one of four boys. Their mother raised them alone. He told the students a story about one of his brothers losing his coat to some other boys in the neighborhood. His mother didn’t have the money for a new one. She told his brothers to go outside and get the coat back, and they did.

“I write about this because of parents who have to deal with violence, and how they worry about their kids,” Canada said. “My mother thought the message she was giving was, ‘Stick up for yourself,’ right? ‘Don’t let people take advantage of you. Be prepared to fight.’ But let me tell you the message I got from that…My mother made them go back outside and fight for the coat? I’m never telling my mother someone stole something from me! I’m gonna say I lost it.”

When he was 9, his mother lost her job and the family moved to a different area of the Bronx. The neighborhood boys there seemed threatening, and it wasn’t long before Canada and his brothers were challenged to throw down in public. What he realized over time, he said, was that the matches were meant as preparation for the reality of living in a community where walking down the street could result in a random violent confrontation at any moment.

Canada held up his right hand. He showed his audience the tip of his index finger, which is permanently bent forward at a right angle. He explained how it got that way: as a young man, he found a knife with a blade that flicked out. He practiced flicking it, wanting to develop a smooth motion like the older tough guys had. On one try, the blade failed to lock and sprung back toward his finger, slicing a tendon. He hid the injury from his mother, not wanting to put his knife in jeopardy.

“The point that I was trying to write about was, kids who feel threatened will go to lengths that most poor folks won’t consider to protect themselves,” he said. “I was so worried about violence, coming up in the Bronx, that I would’ve done anything to keep this weapon just so that I could walk around the Bronx and feel safe. And I never forgot how the world for some young people is so scary, that they are doing things that might imperil them.”

Canada jumped forward to the 1980’s, when he took a job in Harlem. He spoke about the violence that started to reach into the lives of the young people he worked with. Guns hadn’t had a presence in the streets he grew up in. That changed around 1985, he said.

He spoke about that period like a military officer speaks about combat.

“My kids began to be killed,” he said. “We lost the first kid in ’84. In ’85, we lost two kids. In ’86, I lost four kids. In ’87 — in that one year — I lost seven kids.”

Canada tried to understand what was going on. The codes surrounding violence had changed, he said. The fights of his youth used to end at the slightest sign of injury, but disputes weren’t settled by squaring up and going toe-to-toe anymore. Any threat or insult — or merely a perceived insult — could quickly escalate to the taking of a life.

“This was happening to my kids in Harlem, but it was happening to kids all over the United States,” he said. “Mostly, young people who didn’t grow up during my time, they didn’t understand that things had changed; that that wasn’t the way it always was — that you actually had a choice to make when it came to violence. It felt like you didn’t have a choice when I was growing up. Those were the codes…Ok, fine, but it wasn’t life or death. Now, it was life or death, and who was making that decision? A 15-year-old. A 17-year-old. A 19-year-old.”

Canada said that in his experience, the kids who made that irreversible decision always regretted it.

“But at the moment, they were caught up in a set of codes that they didn’t understand,” he said.

The ongoing violence caused him to reflect on how things got that way. The factor he identified that seemed to be changing the dynamic was one he’d felt affect his own mental process: a gun.

Canada recalled returning home on a break from the college he attended in Brunswick, Maine. His mother had moved to another apartment in the Bronx, and his brother warned him about a large group of teenagers who hung out along his route to a nearby store. They were gang members, his brother said. Canada started taking a roundabout route to the store during his visits.

As a resident of Maine, he was eligible to buy a handgun there.

“I said, ‘You know what? Things in the Bronx are getting a little hairy. I’m gonna get a gun.’ So I got me a little gun,” he said. “So now I got the gun, and the gun began to talk to me, right? The gun began to say, ‘Why are you walking all the way around the block? You’re an American. You can walk up the block if you wanna walk up the block. Go ahead, walk up the block.’”

He started walking past the menacing crowd, but on the opposite side of the street. He had to cross it to get to the store. He wondered why he should take the precaution, and started to walk right past them.

They would stare at him. He avoided eye contact, but after another few days of that he tired of that, too. With his gun in his pocket, he started walking past them and returning their stares.

“Let me tell you why I’m here today,” Canada said. “I was gonna kill somebody, and I was gonna go to jail, probably for the rest of my life, because I had that handgun in my pocket. That so changed my way of thinking. It was so powerful, because it wasn’t that the logic was wrong — yes, you’re an American, yes you can walk up the block, yes you have a right to look at anybody you want — but under those circumstances, I was going to end up killing one of those kids, and something occurred to me that said, ‘Your life is gonna be destroyed if you don’t get rid of that handgun.’”

He threw the gun away and never carried a weapon again. And returned to his previous route to the store.

Later in life, he resolved to never again capitulate to his inner voice that urged violence as a reaction, no matter his degree of power in any given situation.

Canada told the students he used to be convinced that the lack of more stringent handgun regulations might change of the victims weren’t so disproportionately minority children. The 2012 massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn. changed that.

“When they slaughtered all those kindergarten kids, they did nothing,” he said. “They did nothing. I think it’s a disgrace. This is an American tragedy. It’s more than 20 years since my book came out and the slaughter continues, and it’s mostly young people being killed.”

Canada followed by answering a few questions. He told his audience that a key element in keeping his students out of trouble is providing them with plenty of responsible adult support and supervision and programs available after school.

Canada has met with President Barack Obama repeatedly, and Obama initiated Promise Neighborhoods, where Canada’s work would be replicated in 20 cities around the country. Canada estimated that there are 150 locations in the U.S. replicating his and his team’s work independently, and another 40 in other countries.

After the presentation, which Canada attended with his wife, Yvonne, he spoke to a teacher about what he said was a fantasy many Americans have about defending their homes from violent intruders. The reality, he said, is that far more guns end up taking the lives of people living in those homes, often by suicide.

“The irony of the fantasy is that the gun actually makes you and your family less safe,” he said, citing a 2008 Harvard School of Public Health study that linked elevated rates of suicide to higher numbers of readily available firearms.

Lisa Dichiara, the school’s library media specialist who organized the event, said the presentation was well-attended by district faculty and administrators, including Superintendent Bill Heidenreich, Board of Education Trustee William Stris and Mayor Ed Fare, who gave his own book presentation earlier in the day.

Dichiara said Canada offered the students a valuable lesson from his personal experience.

“I thought he was a dynamic speaker, and I thought he captivated the whole audience,” she said.