Thursday, April 25, 2024

47.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

47.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

Lorraine Poppe’s legacy will live on

Many families and businesses in the community have made donations to the Poppe Pavilion, the refurbished courtyard at John F. Kennedy High School where students can now study. Further donations will be used for landscaping, more brickwork, plaques and Wi-Fi to make the outside area accessible for concerts, ceremonies and events.

Those who would like to make donations can email the JFK Alumni Association at bellmorejfk1@gmail.com. Checks can be mailed to John F. Kennedy High School, Attn: Alumni Association, 3000 Bellmore Ave., Bellmore, N.Y. 11710. Please write “Poppe Courtyard” on the memo line. A link for PayPal donations can be found at www.bellmorejfkalumni.org.

The association is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

Bellmore’s John F. Kennedy High School was more than just the late Lorraine Poppe’s home for her 23-year career as principal — some said it was her life. Those close to her saw her as a mother, an always-accepting friend or educational mentor. She shaped the school into what it is today, and her influence will live on for generations, through thousands of students.

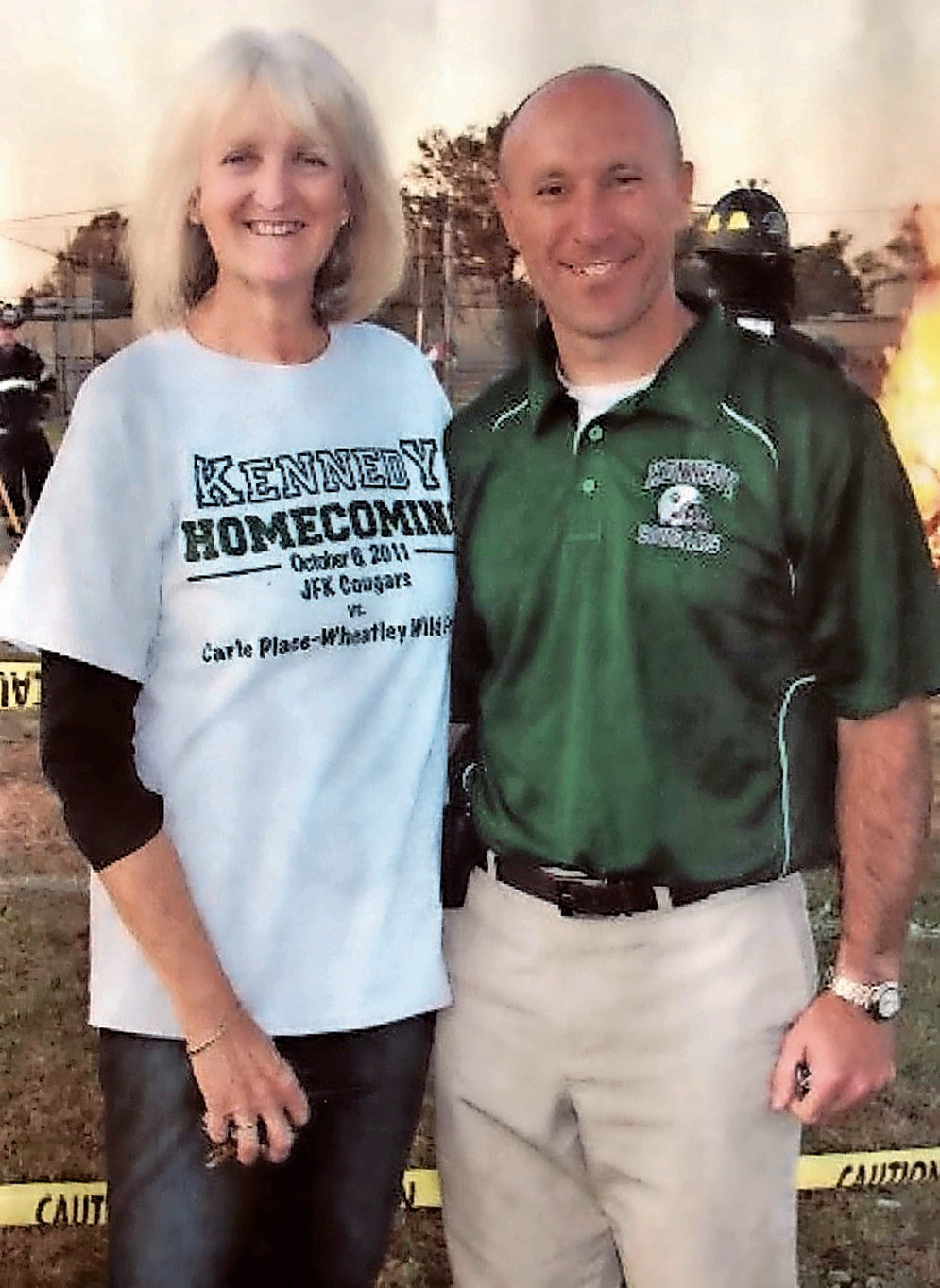

Friends, family and peers agreed that it was rare to find someone like Poppe, who charmed the JFK community. She attended many extracurricular and sporting events, cheering students on as their biggest fan, colleagues said. She had perfect attendance for 18 of those 23 years as principal. She hired the vast majority of the high school’s current staff, and her leadership not only fueled Kennedy’s academic successes, but its ventures into the arts as well.

The beloved educator died in April, after retiring in 2018 due to declining health. She was 67. The Herald Life covered Poppe’s death, including reactions from the Kennedy community, her induction into the school’s Hall of Fame and the dedications to her that followed. Expressions of adoration were abundant.

She was the fourth, and longest-serving, principal of the high school, and her legacy will live on as long as the building stands. Kennedy annually touts academic excellence thanks to her leadership — and the school’s success has benefited the larger Bellmore community.

For these reasons, the Herald is proud to name Poppe its 2019 Person of the Year.

“Her entire time here, she emphasized the importance of being involved beyond just the school day,” said Gerard Owenburg, who was Poppe’s assistant principal for 10 years, beginning in 2007, and took over as her successor in July. In the stands at sports games and science competitions, she sported a Kennedy sweater and a huge smile — “She was the proud parent,” Owenburg said.

“The faculty embraced that,” he added, “and connected with the kids even more so.”

During an interview, Owenburg sat in the office that Poppe once occupied, which has been transformed. Her space was considerably smaller, he said — an adjacent conference room was separated by a wall — but that partition has been removed, giving the office more room. Despite the changes, however, her presence remains, Owenburg said. At times he looked up and pondered his memories of Poppe with a smile that reflected fond times.

Her favorite time of year, he recalled, was Homecoming, when students and faculty alike were filled with Kennedy pride. For her, “it wasn’t just about football, it was about Kennedy,” Owenburg said. Poppe’s excitement about pep rallies, and students’ camaraderie, drummed up fierce school spirit.

Virtually every program outside the traditional high school courses was developed under her watch, Owenburg said. That included the culinary program, which has its own restaurant-style kitchen; advanced science research, in which students undertake professional-level work; Gilder Lehrman Research in the social studies department; and Virtual Enterprise, which turns students into entrepreneurs. No matter what a young mind entering ninth grade might want to study, Poppe made sure that subject could be pursued, he said.

“All of us adopted Lorraine’s pursuit of excellence,” said Eileen Connolly, Poppe’s assistant principal for 19 years. The two taught together in the Baldwin School District, where Poppe started her career as a high school English teacher in 1974. In 1995 Poppe became Kennedy’s principal, and Connolly followed her the next year. “She’s just a class act,” she said. “Anyone that had a chance to work with her is very fortunate.”

The well being of the school and its students always came first for Poppe, Connolly said. She saw her go through “true tests of character,” including when she lost her home to Hurricane Sandy. Poppe’s first concern, though, was her students’ and staff’s safety. With the student government, she helped establish a fundraiser for those in the community who were affected.

“Every year she had the same enthusiasm,” Connolly recalled. “The same dedication, year after year after year.”

Poppe valued student-teacher interactions highly, Connolly said, as evidenced by her relationship with 2008 graduate Rachel Kanner.

“She was crazy about me,” said Kanner, who bonded with Poppe through a shared love of the Mets. Poppe always encouraged support for the team, even when it struggled. “Keep following it and believe in it,” Kanner said she learned from Poppe, which became her mindset for all of life’s hardships.

When the Mets made the playoffs in 2006, Kanner scored a ticket — but it would mean missing a school day. Poppe encouraged her to go to the game, joking that it was a case of “Mets fever.” Their friendship, Kanner said, made Kennedy “feel like a home.”

As Poppe’s health declined, accepting retirement wasn’t easy, her niece Lauren Bowler said. Poppe had never married — Kennedy was her family, Bowler said, adding, “She always held on to the hope that she’d be able to return.” She took a leave of absence in September 2017, and decided to end her career at the end of the school year.

In June 2018, when her retirement was certain, Poppe had one last hurrah with her Kennedy colleagues. It was the faculty’s end-of-year party, and “they lined up to see her one last time,” Owenburg said.

“I’ve never seen 150 people stand and give an ovation like that,” Connolly said. “She got to spend a few minutes with every single person . . . it was a very special day.”

“It was a huge closure for her,” said Bowler, who teaches elementary-school English, “even though she couldn’t retire on her own timeline.”

Posthumously, Poppe continues to transform Kennedy. Outside the principal’s-office windows, in the school’s central courtyard, stands the Poppe Pavilion, a project headed by the JFK Alumni Association. What used to be nothing but broken concrete is now a white pavilion surrounded by tables and benches, an elaborate waterfall and new brickwork.

Before its construction, the courtyard was not open to students during the day. This year it became a space for studying and outdoor classes. “If she could look out the window and see students enjoying the courtyard,” Owenburg said, “it would make her so happy.”

“If anyone deserves it, it’s her,” said Gary Morganstern, president of the alumni association. “The Kennedy community was her children.” The courtyard was originally a vision of Poppe’s he added, “and now it’s the center of the whole school.”

“She’d be [at Kennedy] during the day, at night, at any function,” said Ron Steiger, the association’s public relations director. “It wouldn’t matter — she’d be there.” Steiger, a 1972 graduate, wasn’t a student under Poppe, but when he recounted the Mother’s Day card he wrote on behalf of the alumni for Poppe, he fought back tears.

“Like a great loving and caring mom, you were always willing to give more,” it read. “You have thousands of children to be proud of.”

Just as Poppe encouraged events to be student-organized, Owenburg aims to make the courtyard’s official ribbon-cutting a student-run celebration. It will be accompanied by an outdoor concert.

By all accounts, Poppe was not a fan of awards or special recognition. She was the “ultimate professional,” Owenburg said, who tirelessly, selflessly and humbly gave her all to many of Bellmore’s youth.

“She just was Kennedy High School,” Connolly said.

HELP SUPPORT LOCAL JOURNALISM

The worldwide pandemic has threatened many of the businesses you rely on every day, but don’t let it take away your source for local news. Now more than ever, we need your help to ensure nothing but the best in hyperlocal community journalism comes straight to you. Consider supporting the Herald with a small donation. It can be a one-time, or a monthly contribution, to help ensure we’re here through this crisis. To donate or for more information, click here.

Sponsored content

Other items that may interest you