Four brothers searched Ground Zero for FF Timothy Brian Higgins

Retired FF Joe Higgins recounted discovery of brother's remains

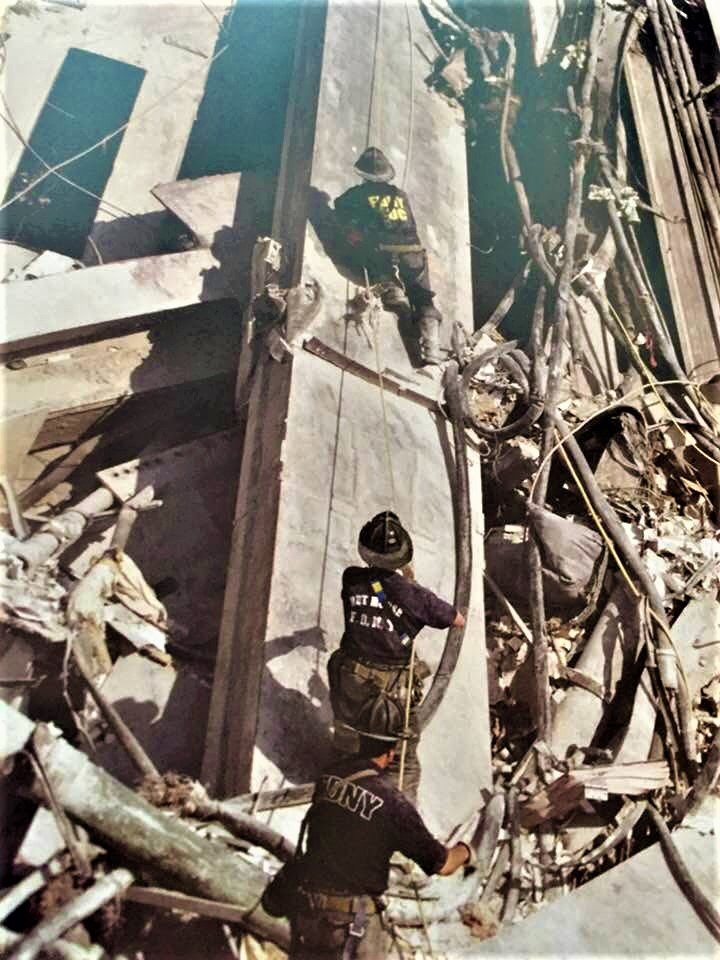

No one recalls the fall of the Twin Towers on Sept. 11, 2001, more keenly than the families of those who died at Ground Zero. Among the lost was FDNY FirefighterTimothy Brian Higgins, who died at age 43 when the South Tower (Tower 2) collapsed. His brother, retired FDNY FF Joe Higgins, told of the search to find Tim in the rubble.

Tim Higgins was the second of five Higgins brothers. The first four -- Mike, Tim, Bob, and Joe – joined the Fire Department of New York. The youngest, Matt, became a detective with the New York Police Department. Their father, Eddie Higgins, was captain of FDNY Engine Company 227. Their only sister, Maureen, became a professional counselor.

Tim was on duty with Squad 252 on the night of Sept. 10, 2001. Around 11:30 p.m., he called Joe to wish him a happy birthday. As they hung up, Joe remembers saying, “Safe at work, bro” — the customary words the brothers spoke to each other as they went on duty at their separate fire companies.

“Those were my last words to Tim,” Joe said. “I was the last one in my family to speak to my brother.”

The next morning, when Joe’s wife called from work to tell him a plane had hit the World Trade Center, Joe knew the FDNY might recall everyone who was off duty.

“I didn’t wait for the recall,” Joe said. “I got from my house [in Freeport] to my firehouse in 21 minutes, which is physically impossible.”

Joe knew Tim was working, but not whether his other brothers were on duty. “I’m flyin’ on the sidewalks and people were letting us go. They all knew the cops and the firemen were going in [to Ground Zero] like killer bees, and I’m thinking, my God, are my brothers working?”

One brother, Bob, was indeed working at FDNY headquarters that morning. He raced down to ground zero, started into the South Tower and dove out of the building barely in time to survive its fall. But Tim was too high in the South Tower to escape.

Their father, Capt. Eddie Higgins, stayed with their mother, Joan, through the next agonizing days. All four surviving Higgins brothers were assigned to search "the Pile” for Tim.

“The media named it Ground Zero,” Joe said. “To us, it was the Pile.”

The search was not hit-and-miss, but was informed by the listing of where each fire company was assigned and by the recorded voices of the firefighters transmitting information. Still, getting started was intimidating.

“Nothing resembled a single office building the first day [of the search],” Joe said.“It was all rubble and concrete and sand and what have you. But guess what? A couple of days went by and you started recognizing things — stair risers and things like that — and you got a guesstimation of when [the firefighters] responded and how high they went up . And hearing transmissions — hearing your brother’s voice on transmissions and hearing people that were trapped and hearing guys saying that jet fuel was coming down and burning on the way down as the South Tower collapsed — and what they were doing, trying to buy time to meet each other, to get themselves out for their evacuations. ... It’s remarkable how these guys tried to cheat time and save their comrades.”

As Joe and his brothers searched the debris, the moment came when they knew they were near the location where Tim must have been when the South Tower collapsed. Recognizing what it would cost them to see his remains in the rubble, the brothers descended the slope of the Pile to ground level. There, they waited while their fellow firefighters unearthed Tim’s body, wrapped it in an American flag and laid it on a gurney. Then the four brothers were called back onto the Pile, where they lifted the gurney together and carried it back down the slope.

“He’s the only one taken down that hill that was a heavy gurney,” said Joe, meaning that very little was found of other victims’ remains. “They found him over a civilian woman.” One of the firefighters from Tim’s firehouse said, “Joe, he was fully intact and it looked like he was waiting for us.”

Even as he and his brothers carried Tim’s remains down the Pile, Joe was conscious that the sense of closure from finding Tim was not granted to everyone. He and his brothers kept returning to the rubble.

“We found four of the five that were lost from my firehouse,” Joe said. “And two of them — we found them the day before they were going to be buried with an empty casket in the ceremony. .... and then we found the headpiece of the firefighter [whose body] wasn’t found. There were people that didn’t find a fingernail.”

Like a caring river, time moved the hurting families further and further forward, away from that worst of all days. Tim’s wife, Caren, stayed in their Farmingville house, raising their three teen-aged children — Christopher, then 17, Catie, then 15, and Cody, 14. Christopher went into forensic psychology, Catie into teaching and Cody into the fashion industry.

Every year, Joe Higgins braces himself as 9/11 approaches.

“I feel it coming on,” he said. “I start having dreams. The other night I had a dream that I was a fireman, and when I woke up I actually thought I was in the firehouse — and I have been retired for 15 years.”

Joe returns every year on 9/11 to his firehouse, Ladder 111 in Bedford-Stuyvesant, for a 9:30 a.m. commemoration ceremony. Then, with his brothers and sister and mother, he drives to Washington Memorial Park Cemetery in Mt. Sinai to visit Tim’s gravesite, where they always find a wreath laid by Squad 252.

Finally, the Higgins family attends Freeport’s 7 p.m. ceremony at the lighthouse-shaped 9/11 monument at South Bayview Avenue and Ray Street.

“The whole town turns out every year there,” Joe Higgins said. “It’s remarkable. The firemen do a color guard, and I feel most comfortable there, to be honest with you. The Freeport thing is truly, truly heartfelt. They never miss a beat, there every year, doing the right thing.”

45.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

45.0°,

Mostly Cloudy