Elmont continues to face high cancer rates

The number of Nassau County residents getting routine tests for breast, cervix and colon cancer has decreased by more than 86 percent during the coronavirus pandemic, County Executive Laura Curran announced at a news conference on July 7.

“This is a nationwide trend, and raises concerns that deadly cancers may go undetected if screening appointments aren’t scheduled soon,” Curran said before introducing Nassau University Medical Center’s new mammography van, which will travel to communities across the county to provide residents with greater access to breast cancer screenings.

In Elmont, residents have complained about high cancer rates for years, pointing out that several residents of the same street have been diagnosed with various forms of cancer. In one case, Mimi Pierre-Johnson said, a man who had lived in Elmont for more than 40 years was diagnosed with medullary thyroid cancer, despite having no family history of cancer. The disease accounts for only 1 to 2 percent of all thyroid cancers in the United States, according to the American Thyroid Association.

“That, to me, was very alarming,” said Pierre-Johnson, founder of the Elmont Cultural Center, which has been studying the high cancer rates in the area.

Breast cancer is the second-leading cause of cancer-related deaths among women in New York state — behind lung cancer — and doctors recommend that women between the ages of 50 and 74 get screened for it every two years. Those who are younger and have a family history of breast cancer, or have noticed changes in their breasts, should also talk with a doctor about getting screened.

In 2016, an estimated 4,470 women in Nassau County had breast cancer, according to data from the State Department of Health, and a total of 25,070 residents were diagnosed with cancer in general — the county with the fifth-highest prevalence of the disease in the state, behind Suffolk, Manhattan, Queens and Brooklyn.

In the early 2000s, the State Department of Health told county officials to expect 153 new cases of prostate cancer in Elmont in the five-year period between Jan. 1, 2008 and Dec. 31, 2013, but the community actually saw 226 cases — a difference of 47.7 percent. At the same time, the county was told to expect 107 new cases in neighboring Franklin Square, and it saw 114 cases — an increase of only 6.2 percent.

More recently, state officials told the county to expect about 124 cases of prostate cancer in Elmont between 2010 and 2014, but in reality, 190 residents were diagnosed — an increase of more than 52.8 percent. They also said there would be an estimated 78 cases in Franklin Square, but there were only 69, a decrease of 12.4 percent.

Officials also overestimated the number of cases of colorectal and lung cancers in Elmont by 31.2 and 18.7 percent, respectively, but were more accurate with other estimates. State officials told their Nassau counterparts that there would be more than 143 cases of breast cancer, and there were 144, and 45 cases of bladder cancer, when there were 42. In Franklin Square, state officials estimated there would be about 83 cases of breast cancer, when there were 89, and 31 cases of bladder cancer, when there were 32.

The state registry accounts for factors of age, ethnicity, sex and genetic predisposition, according to Nassau Department of Heath Epidemiologist Celina Cabello, who said prostate and breast cancers affect African-Americans at higher rates than other ethnic groups. Nearly half of Elmont’s population is Black.

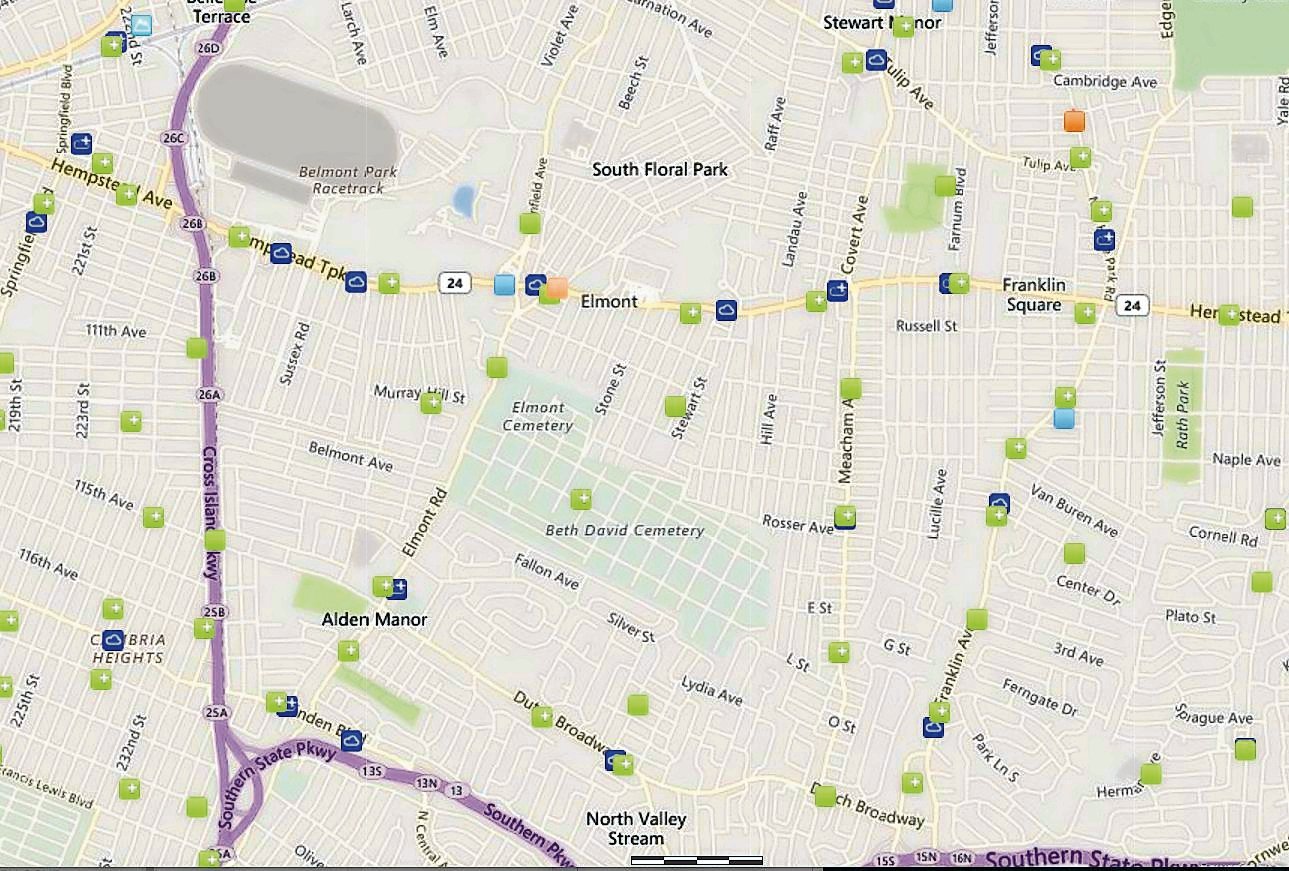

Residents also said they believe Elmont’s proximity to hazaerdous waste sites might contribute to the hamlet’s high number of cancer cases. There are 80 hazardous waste sites in Elmont, and in 1981, the Department of Health discovered that the Genzale Plating Co. Inc., located across Hempstead Turnpike in Franklin Square, was continuing to discharge wastewater into several leaching pits. The pits were not sealed properly, the Environmental Protection Agency reported, and as a result, the contaminants flowed into two aquifers.

Health department investigators ordered Genzale to stop, which it did, but it did not clean up the resulting sludge. Local and federal governments, meanwhile, monitored the company’s cleanup and removed some 30,000 pounds of contaminated dirt between 1981 and 2003. It was designated as a Superfund site in 1983.

No link has been established between the community’s elevated cancer rates and the water, the Superfund site or any other wastewater sites, however, and Genzale was never tagged as a health risk. In 2005, the EPA declared that the aquifer and the Genzale site were safe.

But in 2004, Elmont faced additional environmental contamination when leaky gasoline storage tanks at a gas station contaminated the groundwater with methyl tert-butyl ether and benzene. The State Department of Environmental Conservation cited the gas station’s owners, and when they failed to repair the tanks, the DEC cited them again in 2006. They still did not comply, and were cited once again in 2014. The owners were convicted in 2017.

The DEC found no evidence that MTBE or benzene had polluted the groundwater to dangerous levels, but the water quality reports for the years in question indicated that there were elevated levels of MTBE.

These types of chemicals have been classified as potential carcinogens, according to Geri Barish, president of 1 in 9: The Long Island Breast Cancer Action Coalition, but she noted, some progress has been made. Last year, the State Legislature limited the amount of 1,4-dioxane in the water, and passed legislation requiring large group insurers to cover medically necessary mammograms for women between ages 35 and 39.

“Everyone is working in tandem to ensure that everyone has adequate health care,” Assemblywoman Michaelle Solages said, but added, “no one in this country can pinpoint why the cancer rates are high.”

The only thing people can do, she said, is get tested regularly.