Thursday, April 18, 2024

Glen Cove WWII vet remembers days in the air

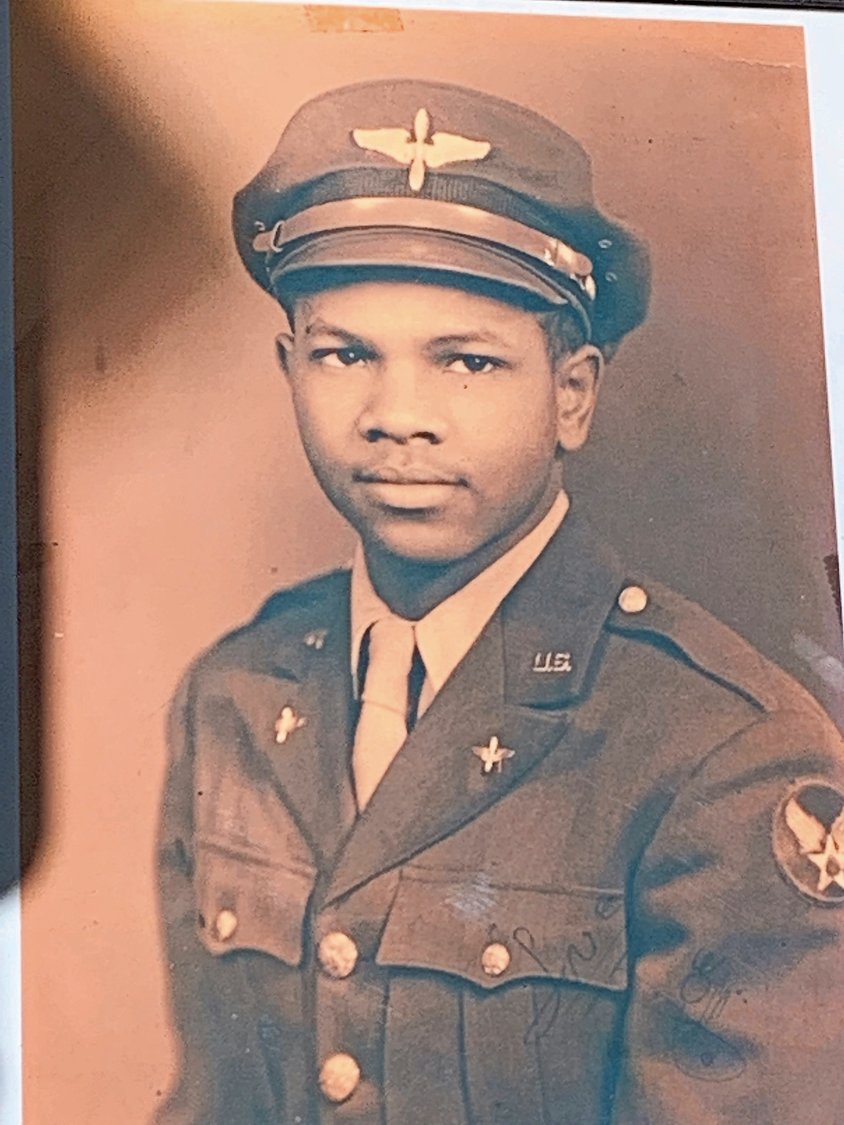

Tuskegee airman recalls World War II

Joe Johnson can often be found sitting on his porch, basking in the sunlight and listening to the sounds coming from his garden. It’s easy to see why. His Glen Cove home is surrounded by trees, plants, statues and chimes, all of which he has planted or installed himself since the house was built in 1961. It makes him feel at peace, he said, and at age 93, peace is among the most important things in his life.

Among the flowers and stone angels, a bright red sign stands out: “Tuskegee Airman.” It is the sole reminder of Johnson’s World War II service outside his home.

The Tuskegee Airmen were black fighter pilots who served in the U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II. Formed in 1941, the regiment was the first of its kind, because black men had never been allowed to fly military planes. Johnson said he knew he wanted to fly from an early age — and he also knew that none of the planes he saw overhead were flown by black men, which was something he sought to change.

William Joe Johnson was born in North Carolina in 1925, the fourth of Lilly and Ellis Johnson’s nine children. His family moved north when he was 4 to escape racism in the South, settling in Glen Cove in 1929. Aside from his time in the military, Johnson has lived in the city for nearly 90 years, attending Glen Cove High School before his service and settling down there afterward.

He graduated from the high school in 1943, after which he was drafted. He joined the Tuskegee Airmen as a cadet, and began training as a pilot. He clearly remembers his first flight.

“I felt great,” Johnson recalled. “It wasn’t that difficult — the biplane just about flew by itself. And I enjoyed it; it was a thrill. I was 18 years old, and I was excited.” He laughed, noting that he flew a plane before he ever drove a car.

As much as he enjoyed flying, the racism he experienced while in training, Johnson said, was another matter. He trained in Nebraska, Colorado, Mississippi and Alabama, and racism was all around him, inside and outside the Army bases. The U.S. armed forces were not racially integrated until 1948, so Johnson and his fellow airmen lived in separate barracks and rode in train cars. White soldiers did not even salute their black counterparts.

Tony Jimenez, Glen Cove’s director of veterans affairs, said the Tuskegee Airmen were one of the most important and influential units in U.S. military history. World War II “was a time when there was a lot of prejudice in the military, and this particular unit rolled up their sleeves and showed that they could perform and were quite capable at what they did,” Jimenez said. “It’s a unit that’s filled with glory.”

Growing up in Glen Cove, which he described as being as racially inclusive as anywhere in the country, Johnson said he had never experienced prejudice like he saw in the South. “They talked [during] that period of time of racism and whatnot in Germany, in Europe, the Nazis,” he said. “Here, it was [almost] as bad . . . lynching, lynching, lynching. When we went out in the public, we had to look at signs that said blacks go there and whites go there. That was America then. America the Great, America the Beautiful and all the other things we sang in school — it didn’t exist at that time for blacks in the South.”

“So I was aware of it,” he added, “but when it hits you straight in the face, it’s a whole different story.” But Johnson’s dedication to service during the war never waivered, though he was eager to return home to Glen Cove to escape that prejudice.

“No matter what it said in the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, it was there in words, but it didn’t apply to black people during that period of time,” he said. “But in Glen Cove, people were more open-minded.”

After he left the service, Johnson attended several colleges as he decided what he wanted to do for a living. He did construction work at first before joining Grumman Aerospace, where he eventually became a supervisor and spent most of his career.

He also attended functions at the Lincoln House, where black Glen Covers often met for a variety of events. There he met his future wife, Alise, whom he married in 1948. They had three children — William Ronald, Terry and Michele — and six grandchildren.

When Alise died of a heart attack in 1989, Johnson didn’t think he would ever remarry. That changed, however, when he met Teresita through a friend. The two were married in 2002, and still live in the home in which Johnson’s children were raised.

“He’s a walking miracle because of the experience he’s had as a black man in this country,” Fred Nielsen, a Glen Cove Marine Corps veteran, said of Johnson. “He’s still so devoted to our status as a free nation in this world, and he has not come to a point in his life of resentment.”

“Whatever happened in the black community of which he was part, and on the national scale of what was on the news,” Nielsen added, “he held dear and close to his chest this dream of what he wanted to do, and he pursued it.”

Although he has done a great deal in his life since his service ended, war, Johnson said, is never far from his mind. He said that he hoped the epic scale of World War II would show people that war would never solve the world’s problems, and he has been disappointed to see that that didn’t happen. “When will people learn?” he asked. “War is not a solution to anything.”

He looked out into his garden, remarking on the beauty of nature and the feeling of the sun on his face as he listened to the chimes and the birds. Finally he said, “Love is the greatest thing. If you had more love, you had less war. That’s what it’s all about. But I enjoyed being a Tuskegee airman . . . it was my greatest adventure, and I am blessed to have been a participant.”

HELP SUPPORT LOCAL JOURNALISM

The worldwide pandemic has threatened many of the businesses you rely on every day, but don’t let it take away your source for local news. Now more than ever, we need your help to ensure nothing but the best in hyperlocal community journalism comes straight to you. Consider supporting the Herald with a small donation. It can be a one-time, or a monthly contribution, to help ensure we’re here through this crisis. To donate or for more information, click here.

Sponsored content

Other items that may interest you