Removal of bridge fence is approved

Neighbors debate fence safety, liability

Albert Morra, a longtime resident of Glen Cove, reminisced as he stood near East Island Bridge on Tuesday. He recalled how he used to carefully make his way down the rocks below to the shore, where he fished.

Morra no longer attempts the climb down, which has become more dangerous, because it now involves negotiating a fence as well. These days, he swings his hook over the opposite side of the bridge facing Dosoris Pond. He said that if the fence were taken down, “Everybody would go to fish.”

Morra’s wish may come true. The Glen Cove City Council approved the removal of three feet of the well-known fence — the portion that is on city property — on April 27. But questions about safety and city liability, raised by residents of East Island, remain unanswered.

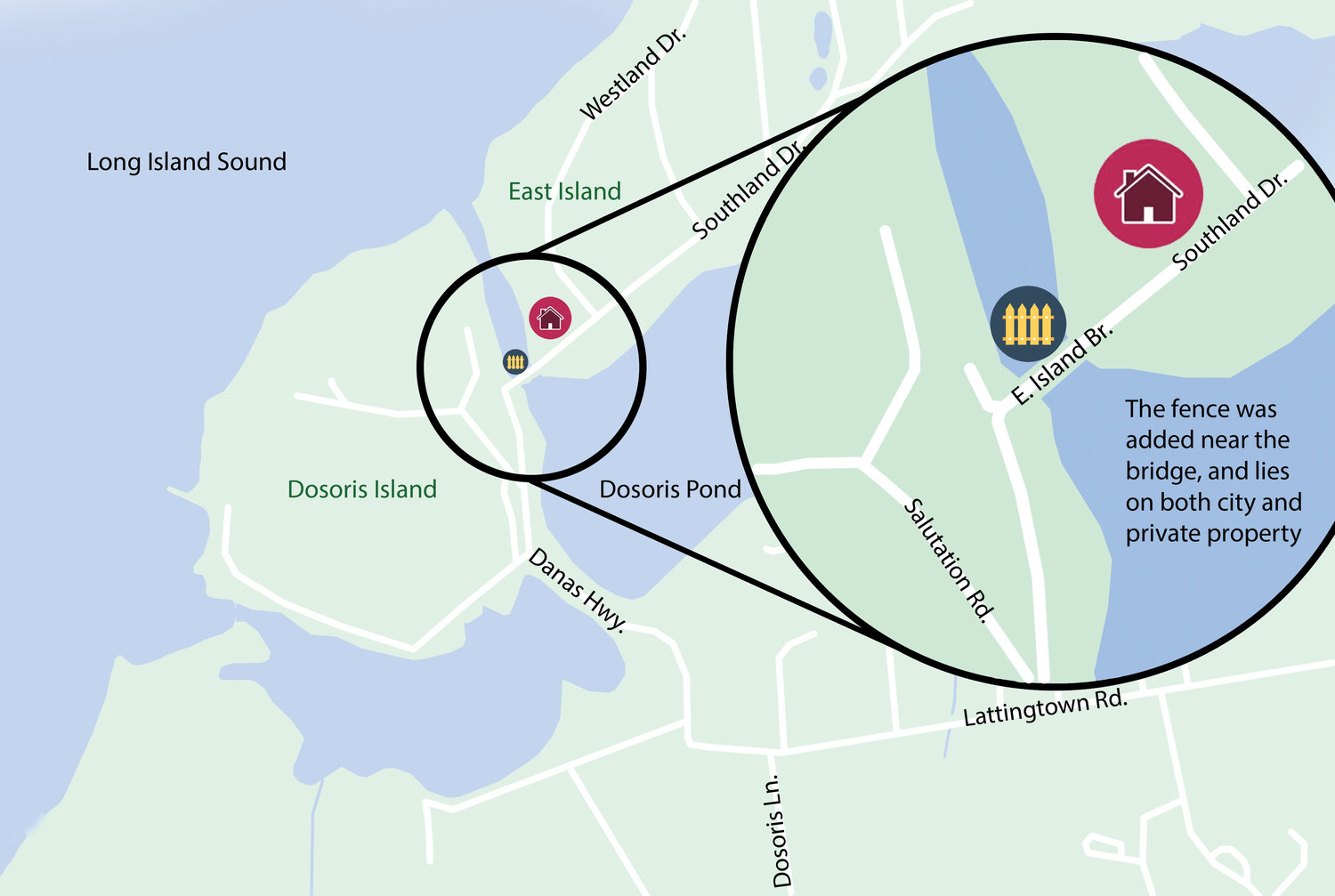

The fence, northeast of East Island Bridge, which was installed last year, during former Mayor Tim Tenke’s administration, lies on both city and private property, at 1 Southland Drive. The shoreline below belongs to the state.

Donald Mumma, who has lived on East Island for four years and is a member of the East Island Homeowners Association, initially thought the fence was a good idea, to limit the number of people making their way down to the shore, as well as the littering and loitering. Many visitors come after the beach closes at 7 p.m. to hang out, Mumma said. Last September, his landscaper found two cases of beer hidden in the bushes on his property.

“If they’re hanging out on public property and they’re littering on my property, that’s something that makes me unhappy,” Mumma said.

Councilman Jack Mancusi, who proposed the removal of the fence after receiving complaints, said that it hinders beach visitors’ rights, since the state opened the shoreline in the interest of the public. “The public has a right to that land,” Mancusi said before the vote on April 27. “You put a fence up prohibiting people from that, they are basically restricting their state constitutional rights to that land.”

Attorney Jeffrey Forchelli, representing Judge Kevin Castel and his spouse, the residents of 1 Southland Drive, asked the council to rethink the resolution at the April 27 meeting. Forchelli’s main argument for a postponement was that the removal of the fence would be dangerous to the public, especially children, who naturally want to venture beyond the fence to the rocks and water.

Removing part of the fence, Forchelli said, would leave the city liable. “I think you’re leaving yourself open to serious lawsuits,” he said. “God forbid, somebody, some kid, jumps and gets hurt and some kid dies.”

At the bridge, the Herald found that walking around the fence toward the Long Island Sound, to the north, and along the seawall was possible, but required lots of caution, especially on the rocks below.

Mancusi said that the fence increased the danger, because visitors might also try to climb over it to get down to the beach. He added that because the beach is state property, accidents would be the responsibility of the state to prevent.

“If the state felt that that land was too dangerous to traverse upon,” Mancusi said, “it’s the state’s responsibility to close it off, not the city’s responsibility.”

There is no other public access to the beach. Even a walk further down Westland Drive and along the shore at low tide requires wading through the water.

The East Island beach, looking out toward the Sound, has been a popular fishing spot for locals and visitors alike for years. Susan Wenner, who has lived on East Island her entire life, said that at low tide, she can take long walks along the shore.

“You would not believe how many people come to fish,” Wenner said. “They got their grandkids (and) they walk across, and they try to fish, sharing the beauty.”

At last week’s meeting, all of the council members approved of removing three feet of the fence except Danielle Fugazy Scagliola, who abstained.

47.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

47.0°,

Mostly Cloudy