Tuesday, April 16, 2024

50.0°,

Fair

50.0°,

Fair

Students push to rename a Malverne village street

In the Village of Malverne, residents have likely walked or driven along Linder Place — named after Paul Linder, an early settler of the community. The street is home to Maurice C. Downing Elementary School, and its name has become a source of controversy over the past year.

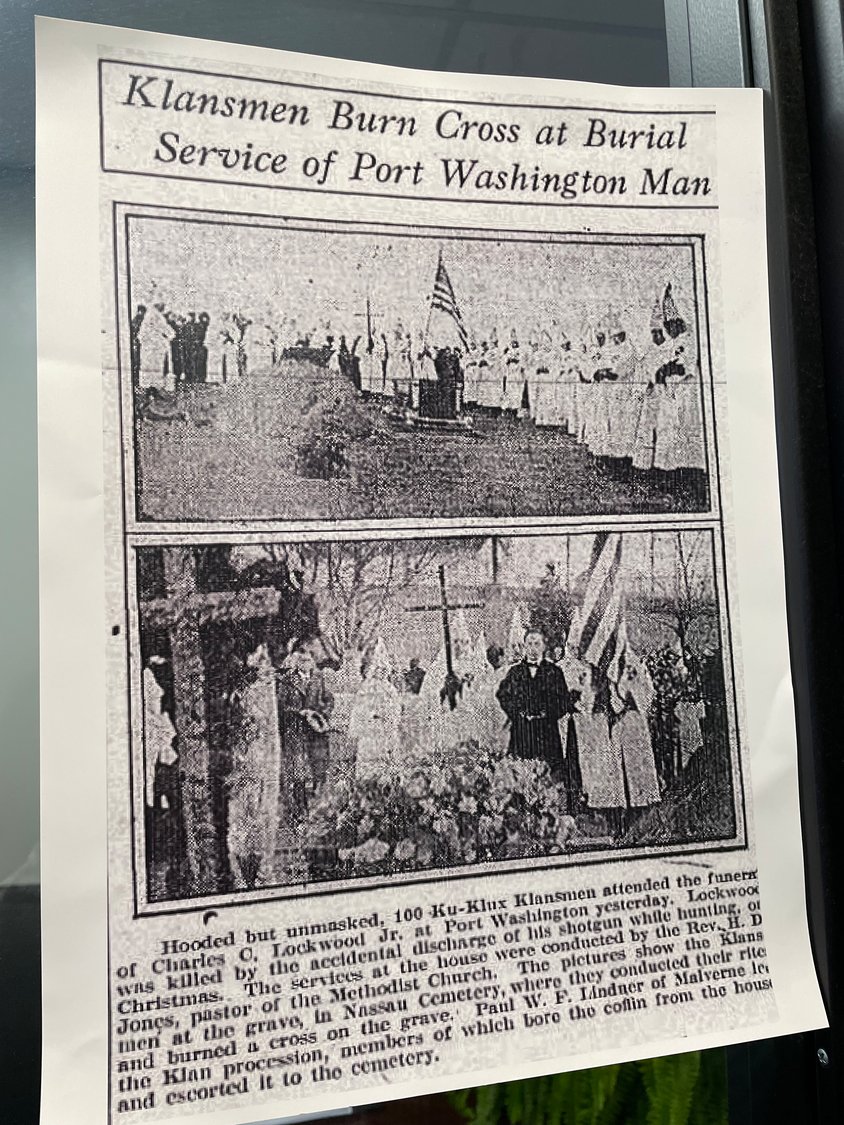

As reported in the Herald in August 2020, Linder was a leader of Nassau County’s Ku Klux Klan a century ago. As racial tensions heightened last year and the Black Lives Matter movement grew, a Unity March in Malverne last summer brought Linder, and the street he named, to residents’ attention.

Since the 2020-21 school year, Malverne High School students have been working on the Linder Place Project, and were invited to present their research — and their arguments for renaming the street — to the village board at a meeting in June. Then, on Oct. 28, students presented the findings of their project at a Humanities Cultural Learning event, “What’s in a Name: The Linder Place Project,” hosted by the district.

In a meeting with the Herald, three of the 17 students who took part in the project, Olivia Brown, 14, Kaila Lawrence, 17, and Sabrina Ramhararkh, 16, all of Malverne, detailed the project.

“We got to pick a side on whether or not we thought the street should be renamed,” Ramhararkh said, “and a lot of us created things like documentaries, art pieces and research essays. We tried to exhibit some of these things and display our perspective on the issues — and also, just raise awareness about the reason why we wanted to have the street renamed.”

At the event two weeks ago, students screened their documentaries, displayed their artwork and read essays aloud to fellow students and other community members.

“At first, I was kind of confused,” Lawrence said of initially learning about the street name. “And then I started to read into it, and started to learn more about its history and background — and I was like, OK, why is there such a discussion?”

“Now, it’s kind of up to the village — you know, the name change,” Brown added. “It’s the people in the town who need to step forward and say that they want to make a change.”

Jason Mach, the Malverne Union Free School District’s supervisor of humanities, explained that the students worked with the Malverne Historical and Preservation Society to learn more about Linder. “At [the Unity March], they were talking about this as one of the potential things that needed to be addressed,” Mach said of the street name. “It either refreshed it or brought it to the minds of . . . a lot of people. It’s sort of something in the town that everyone kind of knew, but sort of wasn’t out there.”

“It was kind of disregarded in a way,” Ramhararkh said. “It was seen as, ‘Well, it’s just the name of a street,’ and while some did think the renaming would be like erasing part of Malverne’s history, other people thought it should be renamed.”

Digging for information

One challenge was the lack of reliable information. “There aren’t many accessible resources for people to educate themselves on this,” Brown explained. “Even if people were aware of who Paul Linder was, and that he was a KKK member — you search his name and there’s not much information that you can receive.”

The NAACP, along with a former student, Kyle Richard, who organized the Unity March, asked the district to encourage current students to research Linder, according to Mach. “After we presented [to the village] in June, the promise was that we would do this again and showcase our students some more,” Mach said. “Thursday’s [event] was making good on that promise.”

The students presented their projects to a crowd of about 40 of their classmates as well as roughly two dozen parents and community members. Ramhararkh screened a documentary she made with a partner, Brown presented an argumentative essay, and Lawrence read a poem. Though the village board was invited, Mach said, members were unable to attend.

Freshman Lorenzo Maione mentioned a July 2020 petition signed by nearly 5,400 people to rename Linder Place Cherry Lane, in honor of Elizabeth Carol Cherry, one of the first Black students to attend Downing Elementary. Cherry eventually became an educator and served the Malverne district for more than 30 years. “If the street were to be renamed to Cherry Lane,” Maione said, “it would be an excellent way to honor Miss Cherry’s legacy and to right the wrong of naming the street after Paul Linder.”

“I would say that most Malverne residents and neighboring towns — because the Malverne School District comprises multiple towns, such as Lakeview and Lynbrook — would want the street renamed,” Ramhararkh said. “It’s their children that go to the [Downing] school — young children — and they go to that school, walk down that street every day.

‘Not who we are’

“When I was first made aware of Paul Linder’s history,” senior Carly Bottitta said, “I could not even believe it to be true. The fact that young children, and myself at that age, walked down a street that exalts this figure of evil every day shakes me to my core. There’s no reason to immortalize and honor Paul Linder, who spread hatred and intolerance to our community. As small as this change may seem, this street name reflects the core values of our town. I know I speak for all of my Malverne family when I say, this is not who we are.”

“Malverne has a very long history of being a school that was integrated on Long Island,” Ramhararkh said. “Long Island has a very long history of being racially segregated, and there’s a history of redlining and gentrification of minorities. Seeing Malverne as being one of those schools that started the integration process, it’s really important that they stay towards that progressiveness and make changes that speak to the community as a whole.”

The school district, in fact, was the first one to receive a desegregation order from New York state in 1966.

“As much as the Malverne, Lakeview and Lynbrook residents want this to happen, very few people have the time to do the research, to write the letters and speak in front of the village board,” Brown said. “[That’s] why we thought it was important to make that our job and be the voices and representation of the school district.”

“I think that what our scholars did is, they took something and made it real,” Mach said. “If people know about it — it’s been 100 years. I think the conversation has been restarted. The students’ work has really brought it back to the consciousness of the people.”

jvallone@liherald.com, lmargaria@liherald.com

HELP SUPPORT LOCAL JOURNALISM

The worldwide pandemic has threatened many of the businesses you rely on every day, but don’t let it take away your source for local news. Now more than ever, we need your help to ensure nothing but the best in hyperlocal community journalism comes straight to you. Consider supporting the Herald with a small donation. It can be a one-time, or a monthly contribution, to help ensure we’re here through this crisis. To donate or for more information, click here.

Sponsored content

Other items that may interest you