Thursday, April 18, 2024

45.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

45.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

Legendary Oyster Bay High School football coach Leonard D’Errico dies

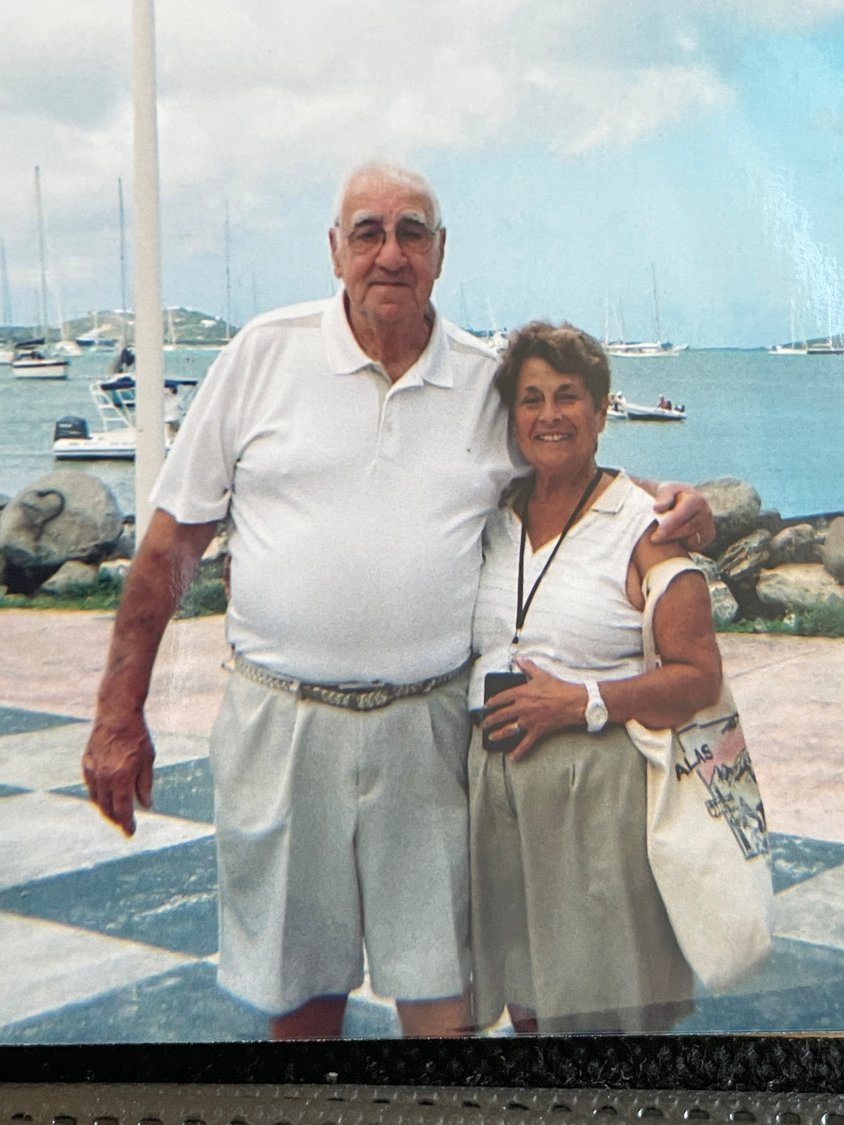

Longtime East Norwich resident Leonard W. D’Errico, 91, a former Oyster Bay High School football coach and phys. ed. teacher, died on March 29 in the Briny Breezes retirement community in Florida.

D’Errico was remembered by many as more than an all-everything football player and coach, named to sports halls of fame in three states. According to friends and family, he was a loving husband and family man, a consummate host and a tough but passionate leader in the community. And in the locker room, he was a “maker of men” who treated everyone he met as family.

D’Errico moved to Oyster Bay in 1966, where, in addition to being head coach in the late 1960s, he taught phys. ed. at Oyster Bay High School and Theodore Roosevelt Elementary School. His wife, Barbara, taught in Floral Park.

“We were a football family — he lived, breathed and ate football,” recalled Diana Hauser, one of the couple’s four daughters. “My mom dragged us to all the games. We never missed a game. We were our own little cheering section — we’d even decorate the car.”

The D’Errico home in East Norwich became Football Central. “We weren’t allowed to watch TV at home — it was game film, over and over,” said Hauser, who still lives in East Norwich.

Football players were always at the house, watching those films. Then Barbara would serve them dinner, usually trays of lasagna.

“He had so much passion for football, and his players,” Hauser said of her father. “It was contagious to them.”

One of those who caught the bug was Butch Garrison, who played at OBHS and went on to become a coach himself. Garrison remembers his old coach as being tough but passionate and loving, a molder of young men.

“Make no mistake about it, Coach D’Errico was a tough guy — he took no nonsense,” said Garrison, who chairs the high school’s Hall of Fame Committee. “. . . You played your heart out for him. He gave me the best high school athletic experience that a person could have. It was like nothing else, and I’ll remember that for the rest of my life.”

D’Errico’s teams compiled a respectable record during his years at the helm. He moved on to an assistant coaching job at New York Institute of Technology before retiring from coaching. And arguably an even more important legacy than win-loss records is the number of young men whose lives were shaped by playing for him.

“My mom and dad continued to hear from so many of his players,” Hauser said. “They’d meet for dinner, talk about old times. They all say he made them who they are — it was because of his high expectations. He taught self-motivation, discipline, a hard-work ethic. That speaks to his caring. He demanded respect, but he really cared about his players. He loved his players and he wanted it to be a family.”

D’Errico was the youngest child of an immigrant Italian janitor and house painter. He displayed exceptional talent on the football field, playing all of the positions on the Cranston, R.I., High School East football team and being named all-state. According to Hauser, after a year playing prep school football in Darien, Conn., her father earned a full athletic scholarship to Boston University.

D’Errico is remembered as a key member of the BU Terriers squad, playing on both sides of the ball — protecting legendary quarterback Harry Agganis as an offensive guard, and playing defensive tackle and linebacker. He was most valuable player and captain of the team in the early 1950s.

Staying on as a scout after he graduated, D’Errico like Agganis, turned down a chance to be drafted by the NFL and instead took a job as head coach at Spaulding High School in Rochester, N.H. In 1957, the team outscored its opponents 315-34, went undefeated and won its second consecutive state championship. The entire offense was named first-team All-State that year. D’Errico, who also served as athletic director at Spaulding, was later described by the High School Hall of Fame there as the “Bobby Knight” of the team.

In Oyster Bay, D’Errico’s passion for football was of a piece with his personal and community life. A member of the Knights of Columbus Oyster Bay Council 1206 and the Italian-American Citizens Club of Oyster Bay, he had a reputation for being an “instant friend to people,” Hauser said. “All my father’s friends said, ‘Len never knew a stranger.’ My mom and dad loved having people in their home, even when they retired to Briny Breezes. Every day there was somebody at their house, drinking espresso or a glass of wine on their patio.”

Mike Antonino, 73, who retired to Florida from Boston with his wife, Amy, met the D’Erricos about 10 years ago. “They took us in — they were like an aunt and uncle to us,” Antonino recalled. “Lenny was always laughing, very smart, and was also very loving. I don’t know how many times a day he told me he loved his wife.”

Antonino said the two would shoot pool every afternoon for two hours, and then the two couples would have dinner together. “He was my buddy,” Antonino said. “They were very generous people, extremely hospitable, and anyhow, we were both paisans, with roots in Naples. We had a lot of karma.”

While D’Errico spent his retirement years in Florida, playing golf and pool with friends and honing his woodworking skills, his legacy, and that of his family, will not soon be forgotten in Oyster Bay.

Hauser continues the family tradition in education, teaching fifth-grade science and math in the Oyster Bay School District. D’Errico’s son Tony lives in Florida, but his exploits on the football field live on: He is an OBHS Hall of Fame member, like his father.

And the third generation of D’Erricos have extended their grandfather’s legacy into the 21st century. Twin grandchildren Nicole and Ryan — for whom D’Errico fashioned beautiful twin wooden cradles when they were infants — excelled on the OBHS athletic fields, and have recently gone on to major universities.

The memories D’Errico leaves behind, as a devoted football coach, family man and light of the community, are still vivid. “He was tough, all right, but he was lovable, a big presence,” Hauser said. “Inside he had a big heart — we knew he loved us more than anything. And when his grandchildren were born, he was a big marshmallow. He was a different person. There were no rules, just lots of love.”

HELP SUPPORT LOCAL JOURNALISM

The worldwide pandemic has threatened many of the businesses you rely on every day, but don’t let it take away your source for local news. Now more than ever, we need your help to ensure nothing but the best in hyperlocal community journalism comes straight to you. Consider supporting the Herald with a small donation. It can be a one-time, or a monthly contribution, to help ensure we’re here through this crisis. To donate or for more information, click here.

Sponsored content

Other items that may interest you