Couple take on police suicides

Beyond the Badge aims to help law enforcement officers

Chris Panetta, 42, rummaged around a closet in his Seaford home earlier this year. In it, Panetta, a New York City police officer for 19 years, found the cards made for him by elementary-school students after the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks, when he was stationed in downtown Manhattan.

“My 7-year-old niece actually made [Chris] a card one day, and I saw how excited he was to get the card,” said Chris’s wife, Michelle, 33, a Nassau County probation officer. “A day or so later, he was in the closet looking for something when he said, ‘Oh! I found the cards. I still have them!’”

Michelle saw an opportunity. “These cards obviously mean something to him if he’s kept them for 18 years,” she said. “So I asked, ‘Why don’t we do Cards for Cops?’”

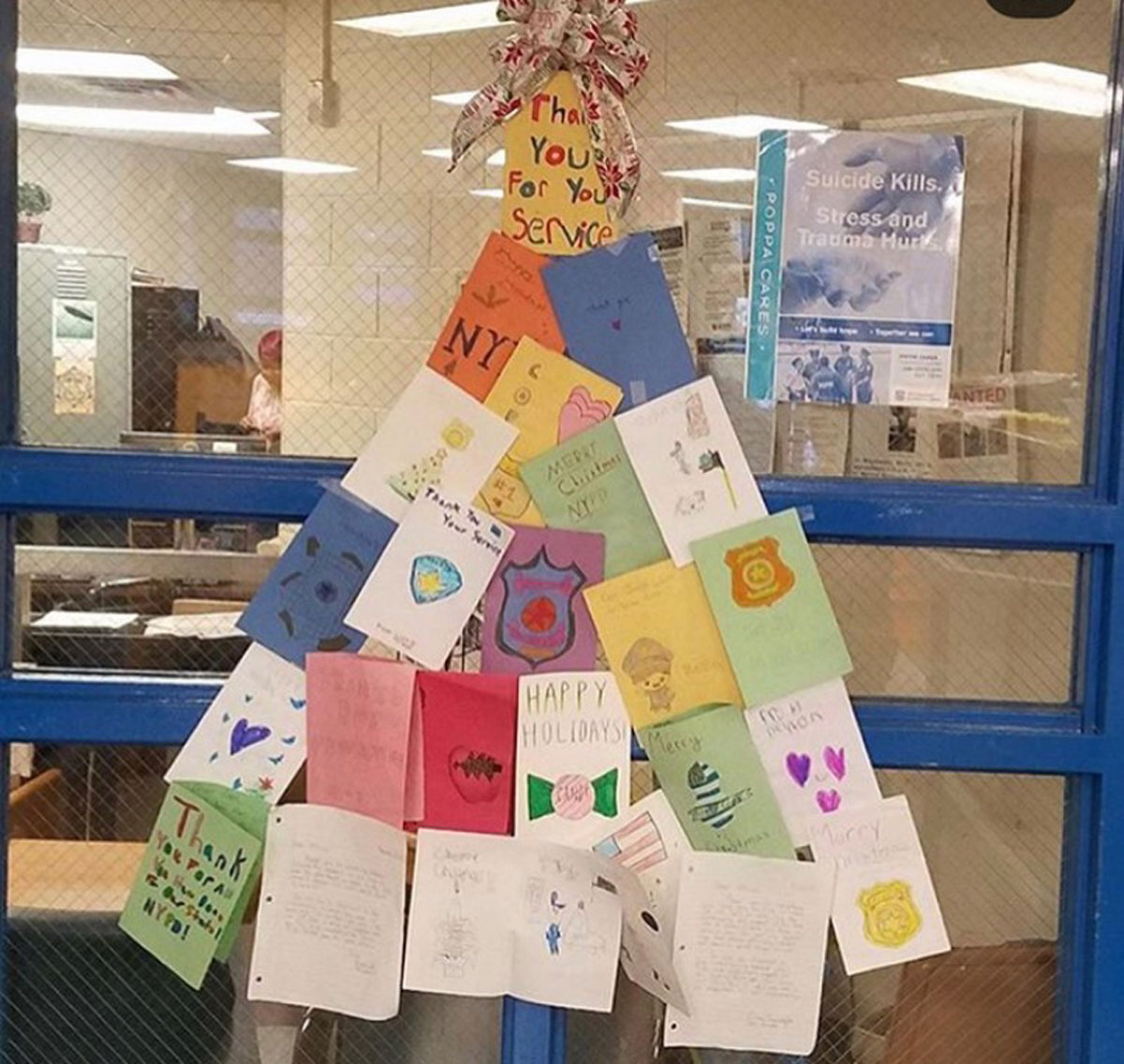

The Panettas started Cards for Cops in November, with the goal of collecting handmade cards from elementary and high school students thanking police for their dedication to community safety and hand-delivering them to police precincts in New York City; Jersey City; a number of villages in Nassau County and the Nassau County Police Department — as well as several precincts in Florida and Texas.

At press time, Cards for Cops had collected 6,045 cards made by students ranging from kindergartners to high school seniors. In addition to Long Island, cards have been mailed in from schools in Queens, Brooklyn, Staten Island, upstate New York and even Pennsylvania.

“I would expect there to be about 6,500 cards by the time we get the last shipment,” Michelle Panetta said.

The inspiration for Cards for Cops was a simple conversation between the Panettas, who are trying to direct the public’s attention to a much more serious topic. “Just this year, I saw a statistic that there were over 200 law enforcement officers that committed suicide,” Michelle said.

“People are scared to talk about it,” Chris added, “but it needs to be spoken about. More people have to know that it’s OK to not be OK.”

According to a report by Bluehelp.org, there were 578 suicides by law enforcement officers in the U.S. from Jan. 1, 2016, to June 31, 2019. In New York state, they make up more than 9 percent of the state’s total suicides — the second-highest percentage in the country, after California, where the number is just over 9.5 percent. The report stressed that these are only the incidents that have been reported, and that the actual number is thought to be higher.

“There has to be a continuing conversation,” Chris Panetta said. “The only acceptable number is zero.”

Panetta, now an NYPD detective, offered some insight into why suicide is so prevalent in the police community. Officers are put in stressful situations time and time again, he said, and often interact with people when “they’re at their worst.” When people are scared, injured, dying, enraged, violent or suicidal, he said, officers have to be there to intervene, and are forced to make decisions with “high stakes.” He added that because is often the norm for on-duty officers, they may be on edge when answering almost any call.

He also emphasized that police officers tend not to speak up when they are dealing with mental health symptoms because

of an unwritten, unspoken stigma. Instead, they internalize their struggles, which can lead to gradual mental health deterioration.

In January, Chris Panetta’s longtime friend Nick Mencaroni, 40, a fellow NYPD officer, died by suicide. In September, the Panettas started a foundation called Beyond the Badge to promote mental health awareness among their law enforcement brothers and sisters. On Oct. 10, Beyond the Badge hosted the inaugural Strike Out Suicide charity softball game for law enforcement at Baldwin Harbor Park, which drew several dozen participants. “It wasn’t supposed to be as big as it was,” Michelle said. “We just wanted people to come out and have fun while supporting the cause.”

Michelle Panetta is an adjunct professor of criminal justice at Nassau Community College. “They wanted to know more about the mental health side of it,” she said of her students, “and this past semester, I taught them [to pay] attention to mindfulness. I feel like a lot of courses focus on what to do when you’re at the job, and not so much about how to deal with the effects of that job when you leave to go home.”

Chris, who has a master’s degree in criminal justice from Molloy College in Rockville Centre, is looking into pursuing a second postgraduate degree in clinical mental health counseling. “I really just want to be someone that people from the law enforcement community can feel like they can come and talk to,” he said. “Sometimes people just need someone else to listen and to empathize with them.”

The next step for Beyond the Badge is to expand — ideally across the country, eventually, but for now the Panettas want to bring about changes locally, by hosting events such as a car show next spring, and offering scholarships to prospective criminal justice students.

“This isn’t about us,” Chris said. “. . . This isn’t about recognition. I don’t care if people know my name, I care if people know the cause.”

44.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

44.0°,

Mostly Cloudy