Sharp divide in test scores

Stats show stark differences between whites and minorities, disadvantaged and better off

Minority and poor students in Rockville Centre are continually under-performing compared with their white and wealthier peers, data recently released by New York state shows.

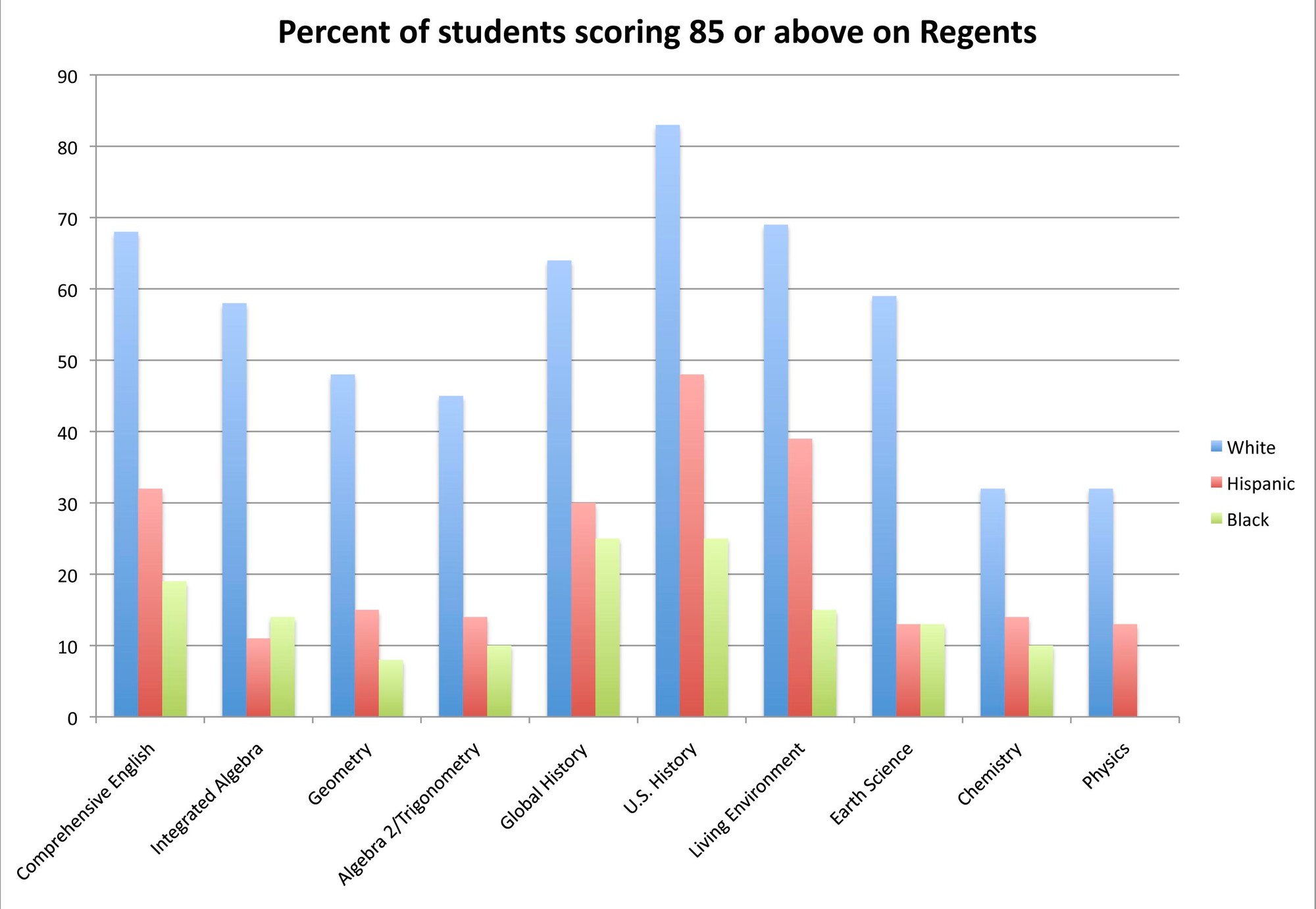

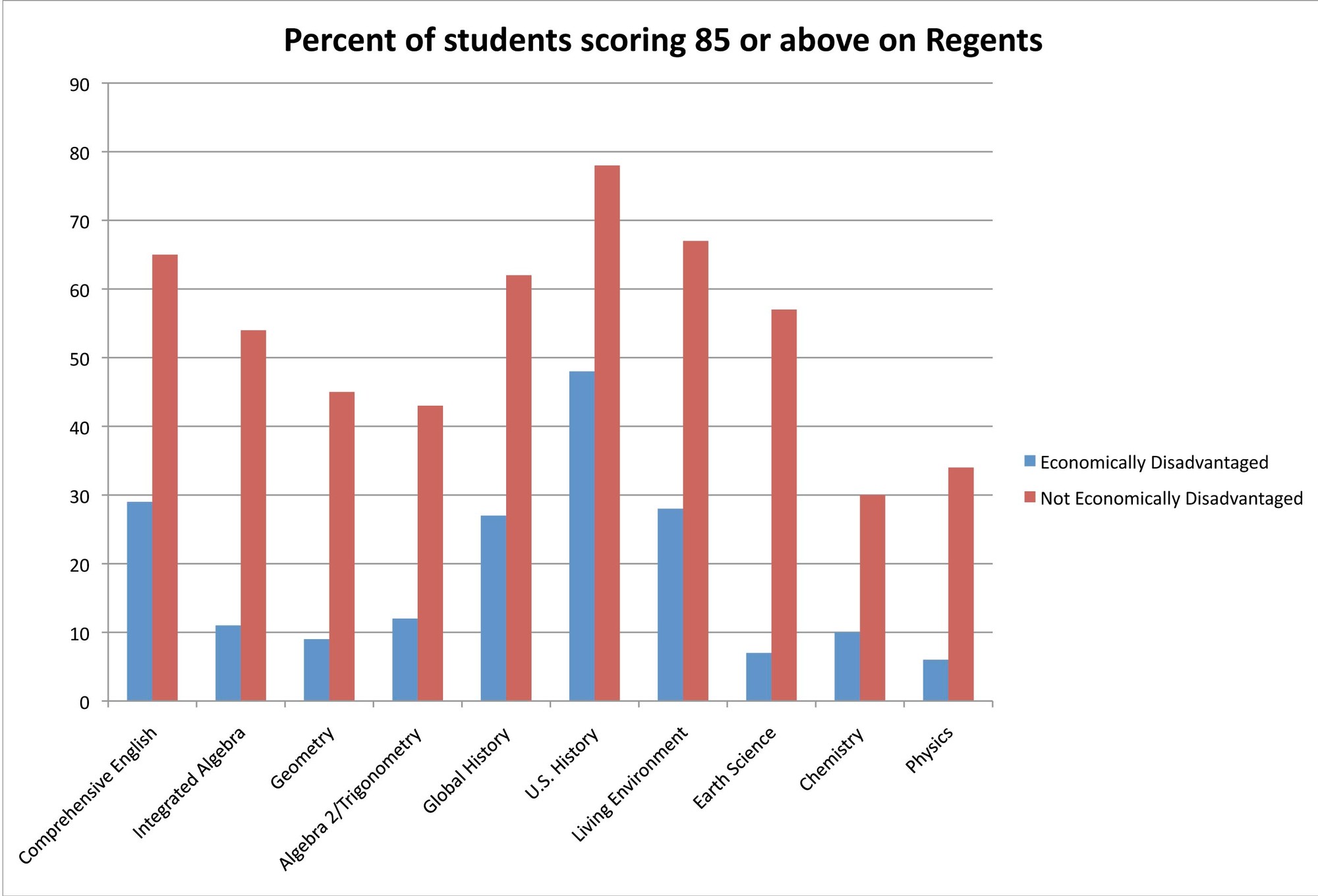

The statistics come from the New York State School Report Cards, which summarize students’ performance on the standardized tests they are given in grades 3 through 8 and, as of this year, the Regents exams. And in every test across the board, minority students in the village — and throughout other districts in Nassau County — performed worse than white students. The differences were even more stark when students from middle class and wealthy families were compared with economically disadvantaged students.

“The problem is not just a Rockville Centre problem,” said Alan Singer, a professor of secondary education at Hofstra University. “It’s not even a New York problem. We’re talking about a national problem.”

Singer said that there are many factors that help explain the weaker performance of underprivileged students. Poorer parents tend to be less literate and have less education, which makes them less able to help their children with schoolwork. They also can’t afford extra academic support for their children. And parents in poorer families often have multiple jobs, Singer said, which makes them less available.

“Poverty makes a difference, no matter how you slice it,” said Rockville Centre Superintendent Dr. William Johnson. “We try to overcome the impact that poverty has on our students here in the school district.”

The state defines “economically disadvantaged” as any student who participates in, or whose family participates in, economic assistance programs, like free or reduced-price lunch.

The data from the state report cards, which can be found at www.data.nysed.gov, is striking: white students in the village are, on average, twice as likely to score 85 or higher on Regents exams than minority students. The percentages are roughly the same for every Regents exam and every grade 3 to 8 ELA and math test.

There is some good news: Though the village’s minority and economically disadvantaged students score below their white and wealthier peers, their results are still well above the state’s average scores. And the majority of Rockville Centre students graduate with Regents diplomas with Advanced Designation, which means that a student passed three math and two science Regents and completed three years of a foreign language.

The graduation-rate numbers, Johnson said, really show how Rockville Centre’s students are doing. “I don’t prepare kids to measure every mile in a 26-mile race, or in this case, 13 years of schooling,” he said, drawing a parallel to the last weekend’s Long Island Marathon. “I want to make sure, at the end of the day, when they finish with us, they can continue their education.”

About 60 percent of the district’s minority students graduate with the Advanced Designation diploma, Johnson said, compared with the state average of 15 to 20 percent.

Students’ under-performance is not an easy problem to solve. “I do believe that if schools consciously address this and systematically develop programs so that the kids feel integrated into the school,” Singer said, “they’ll respond better.”

And that is something that Johnson said Rockville Centre is working toward by encouraging more students to take International Baccalaureate classes. “We have found out that participation in I.B. makes a difference for kids that want to continue their education,” he said. “It also exposes them to a deeper and richer high school experience.

“Just under 90 percent of our disadvantaged kids are in the second year of I.B., and therefore will be sitting for an exam at the end of this year,” Johnson added. “That’s unheard of anywhere. It means that they’re now willing, once they’re together with everyone in the same classes, to take on challenges that their counterparts statewide either don’t have available to them or don’t take advantage of.”

According to Singer, the problem goes beyond the walls of the schools, however, extending to parents and the community as a whole. “This is not just a task for the school, this is a task for the whole community,” he said. “How do we make these students feel they’re a valued part of the community?”

“We need to make sure that families work with us and encourage their children to put in the time and effort outside school to complete all the work that’s assigned to them,” Johnson said. “They need to know that their aspirations are no different than their advantaged counterparts.

“We are working on all of that to change the lives of these kids,” he added. “We’re a work in progress.”