Home for the holiday

Thanksgiving is a favorite holiday for millions of Americans. It’s an occasion to focus on thankfulness and family. Focused on a turkey dinner, it’s a day when families surround themselves with those who are often too far from home.

During the Vietnam War, the Stillwagon family faced the same stresses many military families experienced when a soldier answered the call of duty, specifically the isolation from loved ones during the holidays.

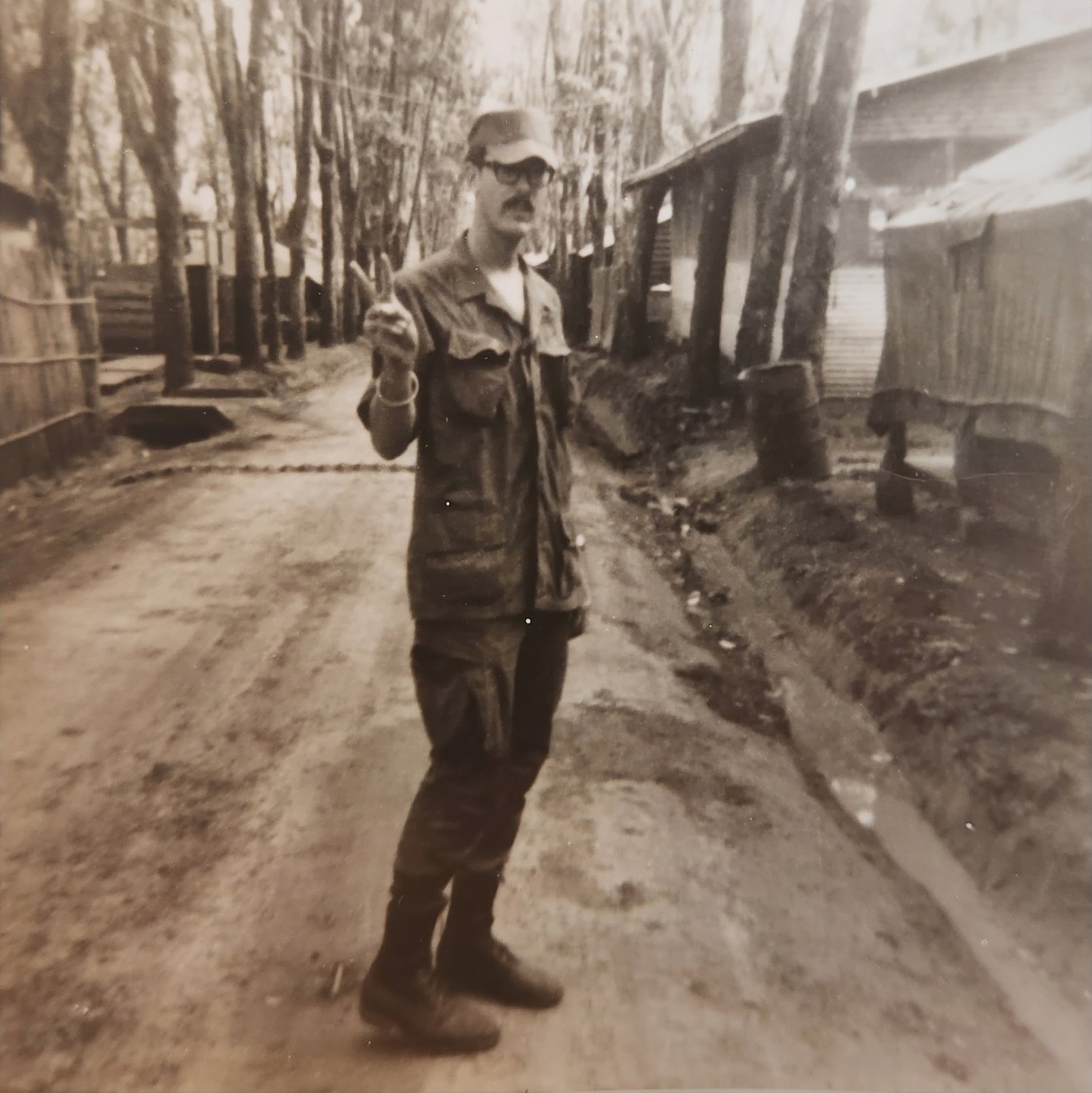

After Glen Cove resident Howard Stillwagon graduated high school, he went to Nassau Community College full time while working at Photocircuits. He was eventually drafted to fight in the Vietnam War in November of 1968. It was the biggest draft since World War II, with the majority of those drafted sent to the infantry.

“They needed numbers, they needed infantry, so that’s what happened to me,” Stillwagon said.

Just before his leave date in December, Stillwagon’s mother was hospitalized with double pneumonia.

“My mom was in poor health,” Stillwagon said. “I was her baby, her son, her only one and having seen my father go through World War Il and wounded twice, she was fearing for me.”

Stillwagon was granted an extension for a few weeks to stay with his mother until she was well enough to leave the hospital. He was immediately called to service after her release.

Stillwagon will always remember that New Year’s Eve sitting at the North Country Bar in the Landing.

“I was pretty much by myself. They were playing ‘Hey Jude’ on the radio because that was the number one song of the year,” Stillwagon said. “I don’t like that song anymore, it kind of reminds me that I was going to Vietnam the next day.”

Stillwagon served in Vietnam for a year and served most of his time on the front lines in the second platoon before suffering a brain injury from a B-40 rocket. Before the rocket struck, he took

helter behind a tree, but received a concussion from the explosion which sent him airborne.

“When I hit the ground, I was dazed,” Stillwagon recalled. “My glasses were gone, my helmet’s gone, my rifle’s gone, and I got (expletive) in my eyes from the explosion.”

Stillwagon heard his parents were trying to get him released from the army on a compassion request given his mother’s continued decline in health.

“(The Army) had gotten letters from a lot of politicians to try to get me at least out of Vietnam anyway or out of the jungles at least,” Stillwagon said.

During his service, Stillwagon frequently sent letters to his family.

“I always wrote because I didn’t want my mother to worry,” Stillwagon said. “I never told her what was going on. I would tell my father and my sister a little bit in the letters but not everything. It got heavy.”

In letters to her son, Stillwagon’s mother said she hoped he would marry a nurse. Back home, Stillwagon’s father protested in a way that was unconventional for a man his age in the late 1960s.

“Howie’s father would not get a haircut until he came home,” said Thomas Staab, a longtime friend of the Stillwagon family.

Eventually, Stillwagon put in for a discharge based on his traumatic brian injury. He was notified that the discharge process had begun and that he was to remain on base in Vietnam until his hearing.

He was ordered by his lieutenant, Robert E. Lee, to return to his unit on the front lines. He disobeyed the order on the grounds of injury.

“They just see you acting normally, and they think you’re good enough to go back out,” Stillwagon said.

From then on, he remained at his base at Quan Loi awaiting his discharge hearing on Jan. 6. Before the hearing, Leephysically dragged Stillwagon to the air strip. He ordered him to get in a helicopter without any survival gear. When he refused, the lieutenant aimed a gun at Stillwagon’s head.

“I said, ‘Go ahead sir, put me out of my misery,’” Stillwagon said.

He would rather have faced death or a court martial than return to the front lines.

Eventually, Stillwagon saw a psychiatrist at another base. He told the psychiatrist about his recent experience and sickly mother at home.

He received a 212 discharge under honorable conditions.

His flight back to the United States felt special, he said. His heart was pounding.

“Everybody was so happy when we were out of Vietnam and over the ocean,” Stillwagon said. “Seeing the Pacific coastline was like a breath of fresh air.”

He landed in Oakland, on Nov. 24, 1969, and was processed out of the Army within a day. On Nov 26, Thanksgiving Day, he boarded an 8 a.m. flight from San Francisco to JFK. When Stillwagon recognized his tall father at the gate and his mother’s red hair, he ran to them.

“My father gave me the bottle of champagne,” Stillwagon said. “I was so happy to see them.”

Stillwagon was welcomed home to a Thanksgiving dinner and felt the heaviness of the emotional day. His mother’s health occupied most of his thoughts. He knew he would never tell her the truth about his time in combat.

One month after his return, Stillwagon’s mother was diagnosed with ovarian cancer. She died 100 days later in March. There was a false sense of optimism the day his mother died. Following surgery to remove her cancer, the doctors were hopeful of a full recovery, instead she passed away from a pulmonary embolism.

“The phone rang at 1 a.m. and my father flew out the door and that was it,” Stillwagon said. “He came home crying. Mom was gone.”

One year after his mother’s death, he met his future wife, Mary Vasko, who was applying to nursing schools. When he was finally ready to talk about his mother, the couple came to the realization that they were already closely connected.

Mary’s mother, Rosemary Vasko, was the nurse treating Stillwagon’s mother after surgery. She can still remember that day vividly.

“My mother came home from work crying,” Mary said. “She was sitting up talking one minute and then the next minute she was unresponsive and gasping for air. That really shook my mother up.”

When Stillwagon thinks about Thanksgiving, he recalls the family he lost over the decades, but he still fondly remembers the impact his return home had on his mother.

“Thanksgiving is still a special day to me 53 years later,” Stillwagon said

54.0°,

Fair

54.0°,

Fair