Locals look to launch marijuana businesses as village considers opt-out

With the passage on March 31 of the landmark Marihuana Regulation and Taxation Act, New York became the 16th state in the union to legalize recreational cannabis use. While the expansive law covers everything from parameters of the drug’s use to enforcement and tax revenue, it also lays the groundwork for entrepreneurs in New York to take advantage of the nascent industry.

State lawmakers have said they do not expect marijuana businesses in the state to receive their first licenses until 2022, as regulatory and taxation infrastructure comes online, but business owners in Valley Stream are already looking to get in on the ground floor of the state’s cannabis industry.

Charlene Ali, a longtime recreational and medicinal marijuana advocate and cannabis entrepreneur, said she has been combing through the 128-page law, and plans to take advantage of the combination of low-interest loans, grants and a business incubator program that it makes available for those looking to get into the marijuana business. Targeted at communities of color that have been disproportionately impacted by the unequal enforcement of drug laws, it was a crucial component to the MRTA, Ali said.

“This is about rectifying so many wrongs that have been happening, especially in Nassau County,” she said.

Black and Hispanic people make up 25 percent of the county’s population, but account for 55 percent of marijuana arrests, according to a 2018 report by the New York Civil Liberties Union. A Black or Hispanic person is four times more likely to be arrested for marijuana possession than a white one, the report read.

While Ali said that discussions with local governments grappling with developing zoning and code constraints related to the sale and use of marijuana would form the bulk of the cannabis industry’s advocacy work in the coming year, whether the law would provide a reasonable avenue for entrepreneurs with modest means to enter the industry would depend on the cost of entry.

“How much will the licensure cost?” she said, noting that in Massachusetts, where she had previously attempted to launch a cannabis business, the price of applications could reach up to $20,000, and competition from large, already established corporations was stiff. Massachusetts legalized recreational marijuana in 2016.

In New York, at least, big business will be unable to corner the market, Ali believes. Under the MRTA, large businesses are unable to vertically integrate into the industry, meaning that no one large company can take over both the growing and selling sides of the business. “That gives us a fighting chance,” she said.

“Every single level has to have separate ownership,” said Assemblywoman Michaelle Solages, a Democrat from Elmont and one of the law’s co-sponsors in the Assembly. “No one can operate both the grow operation and the dispensary. It gives more opportunities for people to get in on the business.”

On the local level, whether recreational cannabis businesses can open and operate in Valley Stream will depend on what decisions the village government makes in the coming months. The MRTA has an opt-out clause for the state’s towns and villages to refuse the sale of marijuana in their jurisdictions. Already on the South Shore, the villages of Rockville Centre, Atlantic Beach, Island Park and Freeport have signaled they would opt out of sales, and the Republican-controlled Hempstead Town Board has also said it would vote to refuse sales in the town, according to news reports. Should they follow through, the municipalities would miss out on around 4 percent of tax revenue generated from marijuana sales.

“We wanted localities to make a decision about what they thought was best for their residents,” State Sen. Todd Kaminsky, a Democrat from Long Beach, said, “both in terms of having more expanded business opportunities and more revenue, but also thinking about public safety and other concerns.”

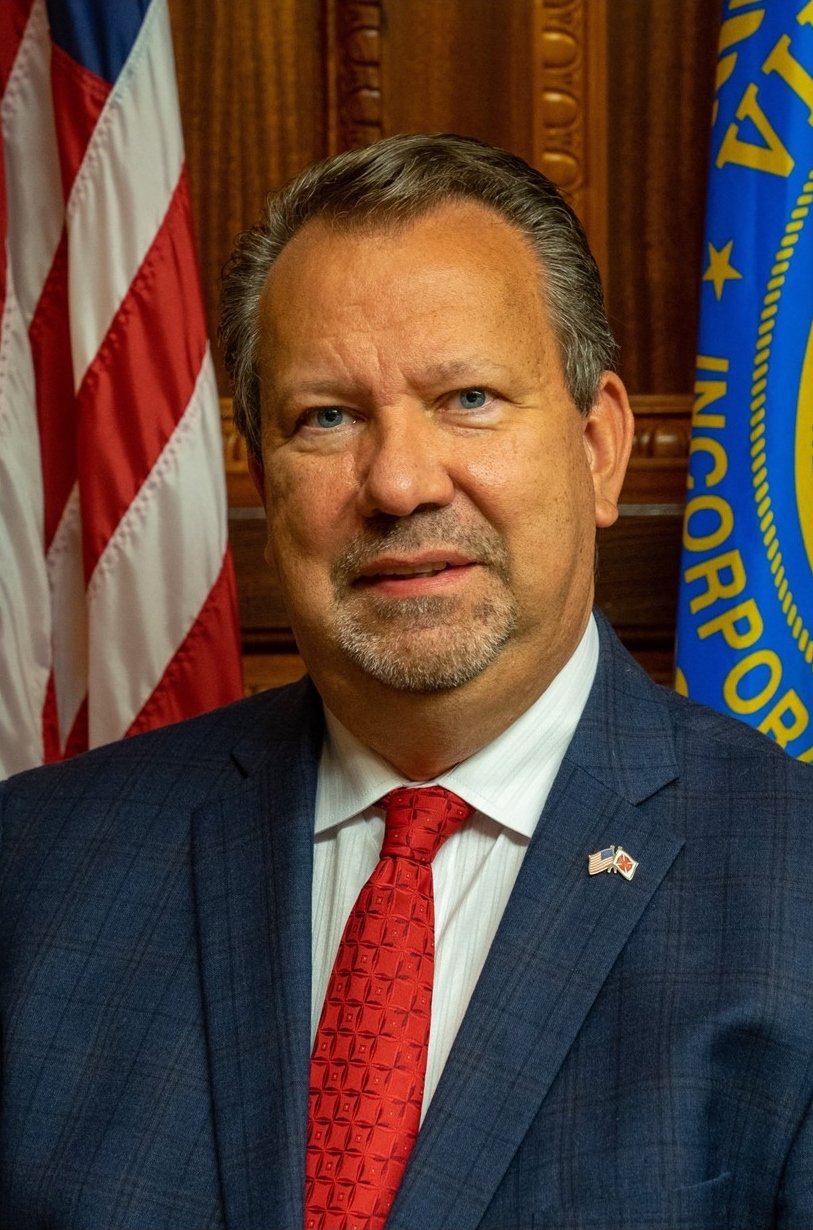

Mayor Ed Fare said he was weighing the pros and cons of allowing marijuana to be sold in the village.

“At first glance, we need to consider the ramifications to our youth and downtowns,” he said in a statement. “Traffic laws and gateway drug issues must be considered. As an educator, I am very aware of the grave risks that drug use and addiction pose to our children, teens and young adults.” Fare is a teacher at Central High School.

Additionally, he raised concerns about public marijuana use, noting the state’s open container laws for alcohol. Under the MRTA, cannabis can be smoked in places where cigarettes are allowed. Much like cigarettes, however, local municipalities have latitude in restricting where smoking is permitted on public property.

“I can’t see trying to raise tax revenues on yet another ‘vice.’ In fact, the probability of villages actually seeing real revenue from the sale of marijuana has yet to be definitively demonstrated,” Fare said. “That being said, there are many responsible adults that already have legal access to alcohol and tobacco, who feel they would now like to access marijuana legally. We understand this perspective, as well.”

Any decision, he said, would come after deliberation between him and the village board of trustees. Trustee Vincent Grasso said he was fully open to the idea of allowing sales in the village, noting that it was a matter of principle for him.

“My entire point of view is that it’s nothing to do with finances,” he said of the potential tax revenue. “I come at it from the point of view that adults shouldn’t be told what they should or shouldn’t put in their bodies either way.”

Should the village opt out of marijuana sales, residents could hold a referendum to override the board’s decision. According to state officials, residents would need to submit a petition with signatures numbering at least 10 percent of the tally of votes cast in the village for the last gubernatorial race.

44.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

44.0°,

Mostly Cloudy