Rallying behind Merrick firefighter in need of a liver

Desperately seeking a liver match for Gleason

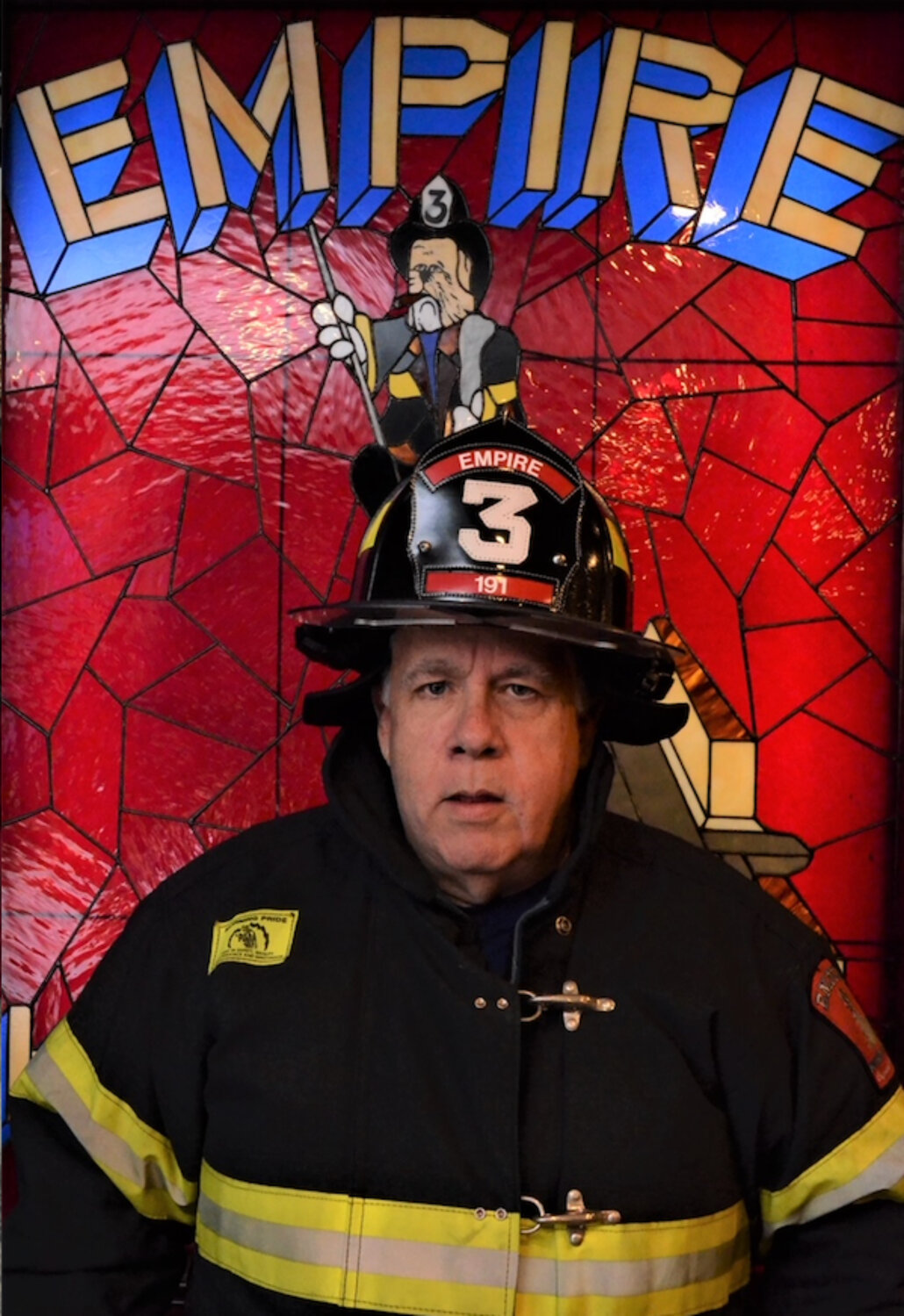

Thomas Gleason, a longtime volunteer firefighter with the Merrick Fire Department, has been waging a courageous battle against liver disease, with his wife Laura by his side. The best chance of survival for the father of two is to receive a portion of a liver from a donor.

Gleason told the Herald that he was diagnosed with liver disease several years ago, due to some conditions like fatty liver and cirrhosis, impacting the liver’s ability to filter blood from toxins, produce bile and carry waste.

“It’s just a hell of a disease,” he said. “I’m not saying it was dormant, but I was holding my own pretty much — things were going okay.”

In 2019, he suffered a bout of hepatic encephalopathy, which is when the liver isn’t processing toxins as it should.

“You get very confused,” he explained. “It kind of mimics a stroke.”

Gleason was born and raised in Merrick, graduating from John F. Kennedy High School in Bellmore in 1984. He worked for a private sign company, and then later worked for almost three decades as a sign maker for the Town of Hempstead. He retired in 2021.

Gleason was stationed at his Empire Hose Company No. 3 firehouse in Merrick when the onset of encephalopathy struck him, and he was quickly rushed to the hospital.

Gleason spent time in the hospital recovering from it, and then began to see specialists at different hospitals, including Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City. But for a while, his liver function, while not optimal, remained stable.

During the early stages of the coronavirus pandemic, when it was hard to access hospitals due to precautions, things became worse, he explained.

“The liver just affects everything — everything in your body, from your hair falling (out) and thinning, to your feet swelling, and everything in between,” he said.

Now, doctors at NYU Langone Hospital in Mineola are overseeing his care, and have begun discussing with him his need for a transplant.

“In terms of a transplant, the only way you can get them is they have these things called MELD scores,” he said. “You have to be at a certain score to even get on a list. And I hadn’t been at that score, but then I hit it.”

MELD stands for Model for End-Stage Liver Disease.

Gleason spent a lot of time in the hospital between last December and January, undergoing tests to assess his overall health in relation to receiving a liver.

“Technically, they say I’m not sick enough to get a cadaver donor right now,” Gleason said, meaning he’d received a liver from a deceased person. “I don’t know how bad, and how sick, I have to be to get to that point. They wanted me to try and find a living donor — which is when a person volunteers, they get checked out, and if they’re a match, we both go into the hospital at the same time.”

Gleason’s friend, Scott Cohen, who lives in Bellmore, has taken the lead, trying to spread the word about Gleason’s condition to see if anyone is willing to help.

In a letter he shared with the Herald, Cohen explained, “A living-donor liver transplant is a surgical procedure in which a portion of the liver from a healthy person is placed into someone whose liver is no longer working properly. The donor’s remaining liver will re-grow and return to its normal size and capacity shortly after the surgery and the transplanted portion will grow and restore normal function in the recipient.”

The donor must be between the ages of 18 and 60, and if over 50, must be in impeccable health, Gleason said. The most crucial aspect to finding Gleason a match for a liver is blood type, which must be O-positive. Gleason also gave permission to receive a portion of a liver from someone with Hepatitis C, a liver infection, because the illness is treatable.

Gleason is not the only member of his family to have faced a medical hardship. In 2006, when his daughter Shannon was 3, she was diagnosed with rhabdomyosarcoma, a highly aggressive form of soft tissue cancer.

“That was just a nightmare,” he said. “She’s tough and she’s had 19 different surgeries. Right now, she’s at Clemson (University). She’s still going to have problems, you know, for the rest of her life. My son’s also a great kid — I just love them more than life itself.”

Cohen said of the Gleasons, “I don’t think I’ve met another family who’s gone through as much prolonged trouble and heartache. We’d love to just put a plea out for anyone who’s willing (to get tested).”

Anyone interested in possibly being a donor for Gleason should call (212) 263-8133, ext. 4. Any contact made with the donor team at NYU is completely confidential. Those interested in getting tested will be sent a script, and can visit any Quest Diagnostics or Labcorp site for basic blood work.

“It doesn’t matter if you don’t know your blood type,” Cohen said. “It’s completely free. The thing that’s really positive for the donor is that they’re saving someone’s life.”