Few Valley Stream students refuse tests

Despite compliance, opposition exists to testing structure

Despite a big push in certain communities on Long Island to boycott the state assessments, few students in Valley Stream refused to take the exams this year which test their skills in English Language Arts and math.

There are more than 4,000 students in third- through eighth-grade in Valley Stream’s four school districts, and only seven chose not to take those tests. Meanwhile, in Rockville Centre, about 350 refused.

Of the children in Valley Stream who didn’t take the tests, six are in District 13 and one is in the Central High School District. Jennifer Leyendecker is mother of two of those students, a son in fourth-grade at the James A. Dever School and a daughter in seventh-grade at North High. “It’s not like I took it lightly,” she said of the decision.

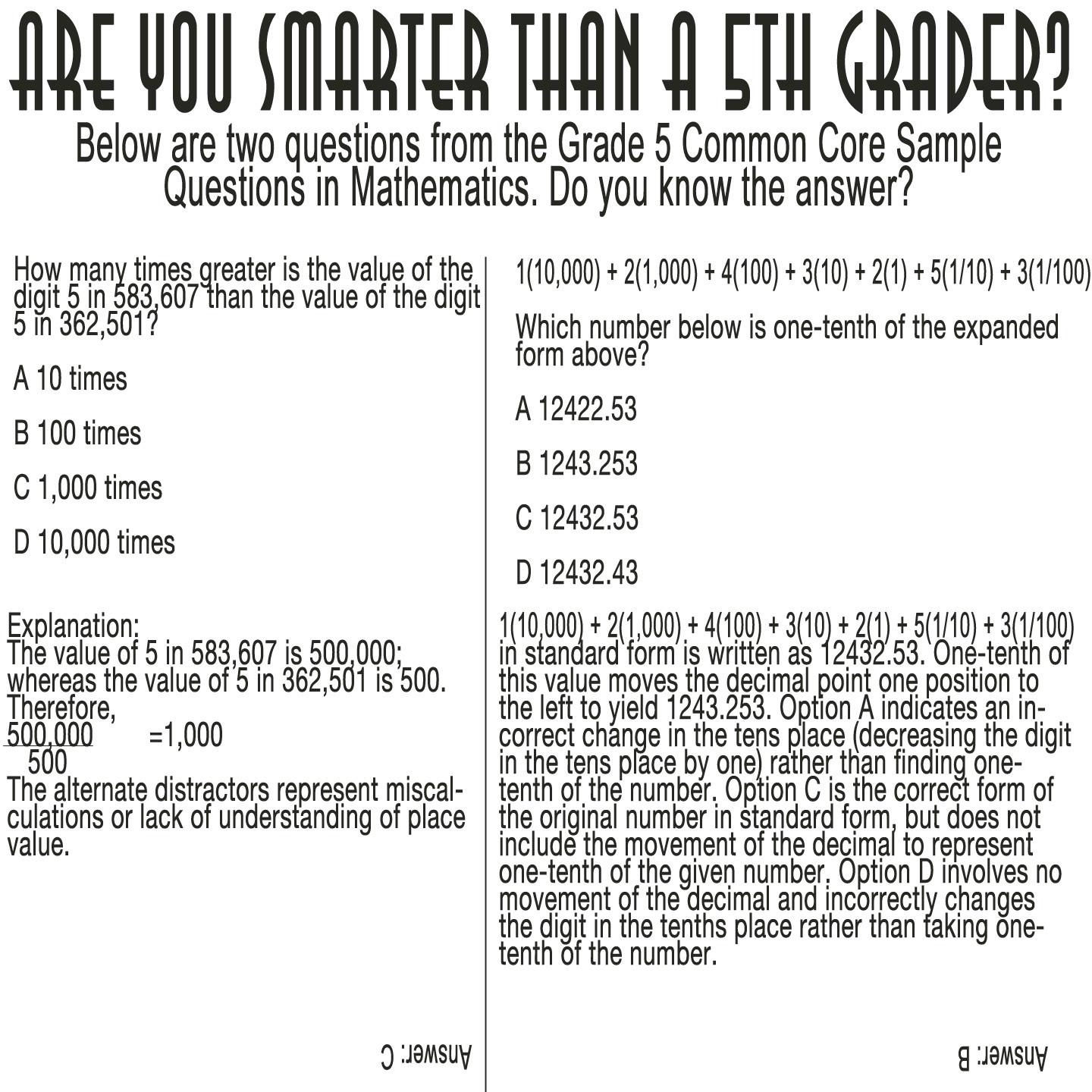

The tests this year are based on the new Common Core Learning Standards which were implemented in all districts in New York state. The more rigorous curriculum is designed to ensure that all students are college or career-ready when they graduate high school.

“They rushed into implementing this new curriculum,” Leyendecker said. “The teachers didn’t have time to teach it. They had to teach to the tests, through no fault of their own.”

There is no provision for opting out of the tests, according to the New York State Education Department. Any student who refuses to take the tests will be recorded as “not tested” and further action is up to individual districts.

Liz Smith, whose daughter is in fourth-grade at Wheeler Avenue School, also decided to take a stand against the tests. She pulled her daughter out of school for the first day of the ELA assessment on April 16, though allowed her to stay the following days to just sit quietly while her classmates were tested.

“We stand behind our decision,” Smith said. “We don’t agree with the way they’re teaching the kids right now.”

Smith noted that there seems to be much more anxiety surrounding the tests than there has been in past years. She said that children are tired and stressed out after school.

In District 13, all students who refused the tests were required to have a signed letter from their parents.

Superintendent Dr. Adrienne Robb-Fund said based on conversations with parents before the tests, she anticipated some refusals. “We knew we were going to have a few,” she said. “We expected fewer than what we got.”

The State Education Department wants a minimum of 95 percent of students in each grade taking the tests. A school that falls below that mark could be designated as a School in Need of Improvement, regardless of how good the scores are. Because District 13 averages about 300 students per grade, six children district-wide refusing the test won’t have an impact on that minimum requirement.

High School District Superintendent Dr. Bill Heidenreich said that while parent uproar was very tame in Valley Stream this year, he said that doesn’t mean more won’t speak out in the future, especially with the protests that have popped up nearby. “It will be very interesting to follow,” he said. “It’s taken a decade, but now you’re starting to see a grassroots parent movement.”

In District 24, no parents kept their children from taking the tests, much to the surprise of Superintendent Dr. Edward Fale.

But that doesn’t mean everyone agrees with the assessments. “I think it’s too much for the kids,” said Lisa Pellicane, a District 24 Board of Education trustee. “It’s become a society where basically we’re teaching our kids to learn how to test take.”

Pellicane has two children taking the tests this year, a sixth-grader at the Robert W. Carbonaro School and an eighth-grader at South High. She said the tests put too much stress on the teachers and students.

“From September to May we’re pretty much teaching our kids how to take a state test,” she said. “We all grew up taking tests, not to this extreme, and we all turned out fine.”

Pellicane and the rest of the District 24 board did pass a resolution on April 17, joining other school districts in calling on the state and federal governments to reduce testing mandates and the role scores play in teacher evaluations.

Smith said the amount of time spent preparing for the tests takes away from time previously spent on other areas like science and social studies. “I remember growing up and having science every single day,” she said. “You had a block of time for each subject.”

Kim Wheeler, president of the William L. Buck School PTA and mother of a son in fifth-grade, said her biggest concern is how teacher evaluations are now being largely determined by student test scores. “It’s fine to test them because it’s good to know where they stand,” she said, “but at the end of the day that’s all I really need to know. What they’re using the grades for is not what it used to be and that’s what’s concerning me.”

Having previously worked as a special education teacher, Leyendecker said she is unsure if she would ever want to return to the field because of the high-stakes testing. She said she doesn’t have any qualms about raising the standards and expecting more from students. What she does object to, is the creation of a school system that revolves around testing.

“It’s very sad what students are going through,” she said. “It’s not like an education used to be.”

52.0°,

Overcast

52.0°,

Overcast