Saturday, April 27, 2024

43.0°,

Partly Cloudy

43.0°,

Partly Cloudy

They were among first black students in schools

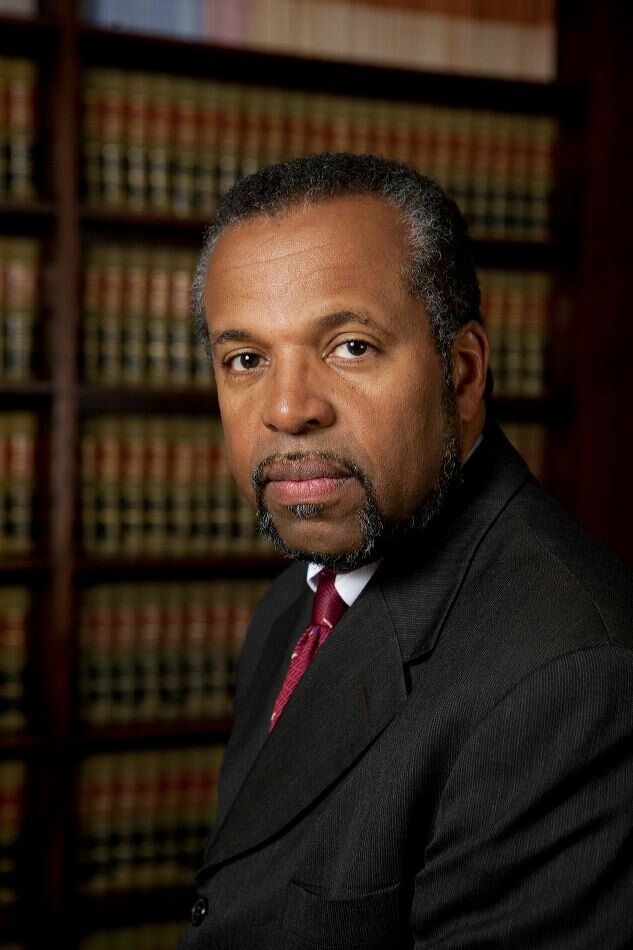

Frederick Brewington still remembers that first day of school when he arrived at Lindner Place Elementary School as a 9-year-old. He was instantly met with a swarm of reporters. They stuck a microphone in his mouth. ‘What did your mother tell you?’ they asked him.

“Walk straight to school, and don’t step on anyone’s lawn,” Brewington, 67, remembered saying, “Because they don’t want you over there anyway.”

It was February 23, 1966, more than a decade after the Supreme Court ruled against segregation in schools — but Malverne, Lynbrook and Lakeview seemingly didn’t get the memo. The children of Malverne and Lynbrook, who were predominantly white, went to Davison Avenue and Lindner Place; the children of Lakeview, who were predominantly Black, went to Woodfield Road Elementary School.

When the district received a court order to desegregate, the community erupted. Protests against integration were vehement, Brewington said — white parents shouting ‘we don’t want you here’ and ‘go home.’ But kids in the classroom, he said, did not share their parents’ vitriol. Brewington was even elected class president from eighth grade through senior year of high school.

“Malverne turned into a great, wonderful learning experience,” Brewington said, “For so many people who may not have had the opportunity — or may not have taken the opportunity — to learn about the things that make us similar as opposed to the things that can separate us.”

Among the biggest problems in the district, said Robin Delany, 71, said was the lack of representation. The all-white board strongly resisted integration, and filed a lawsuit against the executive order to desegregate. There were only one, maybe two, Black teachers in Malverne High School. There were zero Black administrators.

“The guidance was terrible when it came to Black kids,” Delany said. “Their expectations were so low.

“I remember being in the guidance office and watching a fellow student being told by one of the guidance counselors that he should go into the military, because he couldn’t do anything else.”

Delany was among the group of students who presented the Board of Education with a list of demands. Among them: teach Black history; hire Black faculty; use the word “Black” instead of “Negro” in the school paper; acknowledge Martin Luther King Day as a holiday; change the name of Howard T. Herber Middle School, because it was named after a racist superintendent.

The board agreed to teach Black history and hire more diverse faculty in the future. All other demands were ignored.

So the student activists — and a few parents — had peaceful marches through the community. They boycotted classes. Finally, they had a sit-in. Delany was among the 137 arrested for participating. The police then strip-searched the students. Delany was 15.

“We’re trying to encourage our kids to be civically engaged,” Jeanne D’Esposito, vice president of the Malverne school board, said. “We want our children to know that they have power.

“So if the board isn’t listening to them, we’re giving them the exact opposite message — that they don’t have a voice, that they don’t matter, that they shouldn’t even bother getting involved.”

Malverne today

Brewington became a prominent civil rights lawyer and community activist. Delany worked for the Federal Department of Justice for 25 years in the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

During a high school reunion two years ago, she listened to what her former classmates have done in the last 50 years. One was a nurse. Another was going back to school at 69 years old for a Ph.D., and is running a nonprofit in Texas. Another became a pilot. Seeing classmates realizing their aspirations despite the racism they faced in school was striking, Delany said. She is similarly gratified by the Malverne school district’s success today.

“There’s a very high population of color there,” she said. “And those kids are excelling, and getting scholarships, and so on.”

Part of the benefit of Malverne isn’t just the education in the classroom — it’s the education from the classmates. Having a diverse school body is not a melting pot, Brewington said — rather, it’s a five-course meal. Appreciating the different tastes and smells and textures is what makes a wonderful culinary experience.

“That’s what our community should be,” Brewington said. “We get the best from each other, and because of that we’re all better.”

But the struggle for equity on Long Island is far from over. A study by the civil rights group ERASE racism found that Nassau County is one of the most racially segregated regions in the country. They also found that “intense segregation” in the county’s school districts had more than doubled between 2005 and 2017.

“Every time we push back,” Brewington said, “Every time we say ‘don’t teach Black history,’ every time we say ‘I don’t want to learn about that,’ every time we see a degradation of other individuals based on their race, religion, background, et cetera, we are creating an anti-learning process.”

More than anything, Delany wants to see the students of Malverne and Lakeview pick up where her generation left off. And most importantly, she said, they must know they can’t do it alone.

“If you don’t know that you can succeed when you come together, organizing and challenging injustice, then you’re less likely to do it again,” she said. “You want those examples, you want to understand that you can succeed, you want to understand what happened in your own community.

“You need to know what came before in order to understand what you should carry forward and what you need to change.”

It seems, though, that Malverne and Lakeview students are carrying that torch. The student-led project “What’s In A Name?” saw Lindner Place — named for Ku Klux Klan leader Paul Lindner — renamed Acorn Way. School administration is partnering with the NAACP and the Lakeview Civic Association to plan a celebration for the 60th anniversary of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. marching down Woodfield Road.

“We’ve been fortunate enough through the latter part of the 20th century into the 21st century to see change,” Brewington said. “But there is no time to rest, because people died so that we might be able to advocate and make the change.

“That’s who we stand on — we stand on their shoulders.”

HELP SUPPORT LOCAL JOURNALISM

The worldwide pandemic has threatened many of the businesses you rely on every day, but don’t let it take away your source for local news. Now more than ever, we need your help to ensure nothing but the best in hyperlocal community journalism comes straight to you. Consider supporting the Herald with a small donation. It can be a one-time, or a monthly contribution, to help ensure we’re here through this crisis. To donate or for more information, click here.

Sponsored content

Other items that may interest you