The forgotten Wall Street bombing

My great-aunt, Caroline Dickinson, stood on the corner of Wall Street and Broad Street at noon on September 16, 1920. She normally went out earlier, but she was meeting a friend for lunch and then taking the woman back to her job, the George H. Burr Company, to interview for a stenographer’s position.

A red horse-drawn wagon rolled to a stop in front of 23 Wall Street, the headquarters of J.P. Morgan. The wagon was loaded with 100 pounds of dynamite and 500 pounds of cast-iron sash weights, or long, heavy counterweights used in the operation of Victorian windows. As the woman approached my great-aunt, she heard an earsplitting explosion and saw Caroline fall to the ground, killed instantly by a metal slug that severed her carotid artery. A total of 38 people were killed, 143 were seriously injured, and hundreds more sustained a range of injuries. There was $2 million in property damage, mostly to the interior of the J.P. Morgan building.

The timing of the bombing was designed to create the most damage, loss of life and chaos since Wall Street brokers, messengers, clerks and stenographers were going to lunch on that beautiful, sunny day. The blast blew out windows, lifted people off their feet and threw a trolley off its tracks. Human carnage was horrific — dead bodies and body parts were strewn in front of 23 Wall Street and the adjacent Federal Building. Police officers quickly commandeered all nearby vehicles to take the injured to local hospitals.

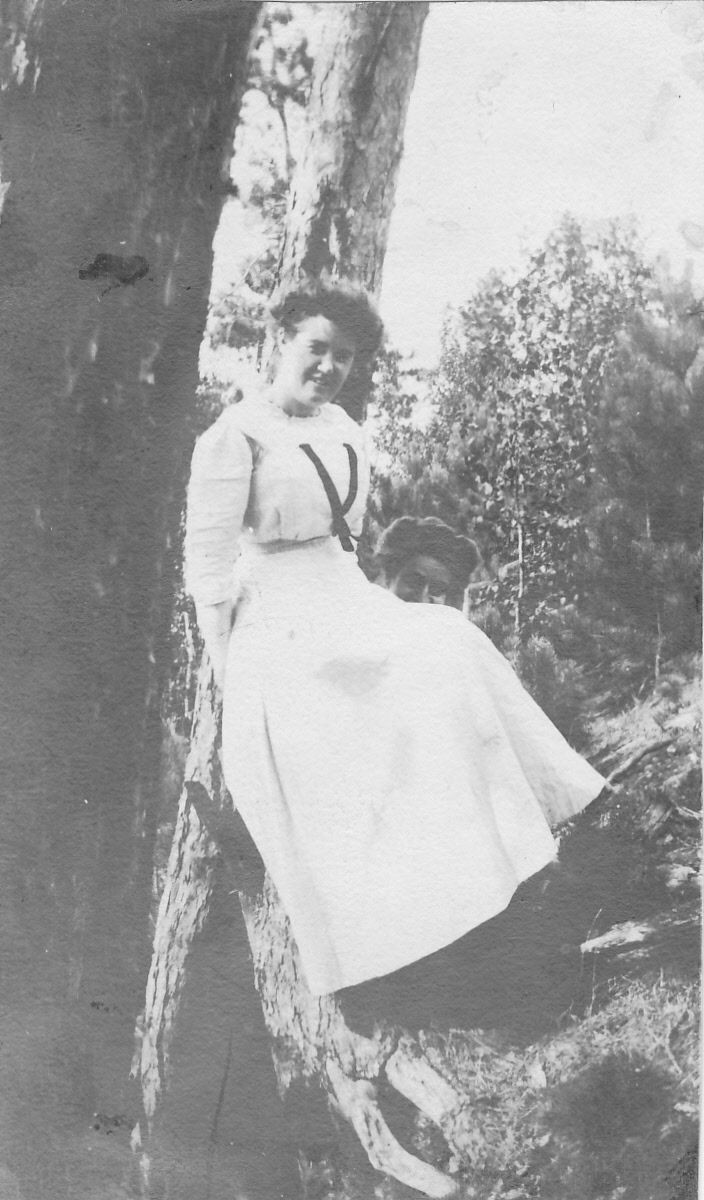

Carrie, as my great-aunt was known, was a 43-year-old stenographer living with and supporting her widowed mother in Elmhurst, Queens. I never had the chance to know her. As a child, I was often told that she was killed in the Wall Street bombing. I didn’t have an understanding of terrorism. Her death was the third for the Dickinson family in less than a year after the passing of her father and brother. My grandfather, Clarence, had the sorrowful task of identifying his sister’s body at the morgue.

The only remaining reminders of the bombing are some markings made by shrapnel on the façade of 23 Wall Street. There is no memorial for the victims. The only commemoration was a rally the next day, Sept. 17, 1920, by the Sons of the American Revolution at the site.

The perpetrators were never caught. The driver of the wagon evidently escaped before the explosion and little remained of the horse and wagon. Galleanists, or Italian anarchists, were suspected of initiating the attack as retribution for the arrests of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, two anarchists who were later convicted of murdering a guard and paymaster in a shoe factory in Massachusetts. Another possible motive was the deportation of Luigi Galleani, an advocate for the violent overthrow of government institutions. The placement of the bomb in front of the J.P. Morgan building suggested opponents of capitalism, such as Communists, anarchists, Bolsheviks or socialists.

Wall Street financiers sought to minimize the event by having the area cleaned overnight so that business the next day could proceed as usual. The quick cleanup destroyed valuable evidence. The New York district attorney branded the bombing an act of terrorism aimed at Wall Street and J.P. Morgan due to the timing, location and method of delivery.

A three-year search by the Bureau of Investigation and local police did not result in any conclusive evidence to bring a specific group or individual to trial. Tennis champion Dennis Fischer was questioned because he sent postcards to friends warning them to leave the area before September 16. He was eventually sent to an asylum, diagnosed as insane but harmless. Flyers were discovered in a post office box in the Wall Street area that stated, “Remember, we will not tolerate any longer. Free the political prisoners, or it will be sure death for all of you,” signed by the American Anarchist Fighters. The group was never found. A theory advanced by several historians is that Mario Buda, an associate of Sacco and Vanzetti, planted the bomb. Buda was a knowledgeable bomb maker who was implicated in several other bombings. He was in New York City at the time of the bombing but wasn’t questioned or arrested. He traveled to Naples using the alias Mike Boda, and never returned to the United States.

Ninety-five years after the bombing, the people behind this tragedy remain a mystery. Sadly, we have endured the Oklahoma bombing, 9/11 and other acts of terrorism, but in each incident, the architects were discovered and punished. Memorials were established for the victims of those attacks with annual commemorations of their loss. There was no such memorial for my great-aunt and the 37 other victims who were in the wrong place at the wrong time. A simple plaque on 23 Wall Street with their names would be a way to honor and remember the lives of these innocent people.

The author is a Valley Stream resident and trustee of the Valley Stream Historical Society. She is a retired associate professor and director of the graduate program in literacy and cognition at St. Joseph’s College in Patchogue.

43.0°,

A Few Clouds

43.0°,

A Few Clouds