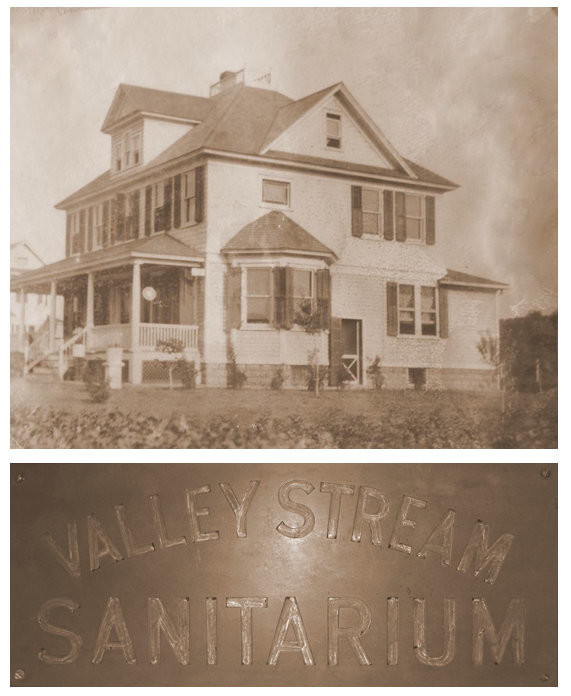

A hospital’s origins: the Valley Stream Sanitarium

A stately house used to occupy 392 W. Merrick Rd., on the southwest corner of Merrick Road and Montgomery Street. Called the Queen Anne, it boasted three stories of almost 3,000 square feet with a wrap-around porch, a widow’s walk and open land in the back. Today, it is a lot filled with shiny new cars that belong to the Acura dealership.

The site was once the location of a nursing home whose proprietor would help bring about the establishment of Franklin Hospital.

The provenance of the building and its land is an integral part of Valley Stream history. In 1893, the Royal Land Company developed the west end of Valley Stream and named the area Irma Park. A Bavarian immigrant and longtime village resident, William “Billy” Smith, owned a large chunk of real estate in Irma Park, later renamed the West End. In addition to his two-story home, which ran long and deep, the former tailor owned and operated a clothing manufacturing business dating back to the 1870s. Smith was also the proprietor of the Irma Park Hotel, a Civil War-era inn that opened in the 1890s. It became the world-renowned Pavillon Royal nightclub in the 1920s. In 1906, Smith died and Joseph Buscher, a German-born butcher, bought much of the land in Irma Park. In 1908, Buscher built the Queen Anne between the old Smith homestead and the Irma Park Hotel.

He died in 1930, and the history becomes murky. It is likely that the Buscher family suffered financially after Joseph’s death. Classified ads with this address, dated 1932 through 1934, vary in content. One lists “furnished rooms for let, board optional.” Another describes the property as “a beautiful estate, horses, swimming pool, sports, dietician.” One that caught my eye, from the November 25, 1933 Nassau Daily Review Star: “Unsuccessful in love or business? Consult a well-known psychologist. Also choose your vocation by successful hand-reading. Yovana.” The last ad I found, remarkable in its range of rental opportunities, but cryptically worded, was from the May 22, 1934 Long Island Daily Press: “Concessions for rent – check room, parking space, cigarettes. 500 seats, prominent restaurant, adjoining Pavillon Royal.”

Now imagine the Acura parking lot, once the Buscher homestead, as the Valley Stream Sanitarium.

In 1926, Edward “Eddie” Strauss and his family moved to 42 South Montague St., located a block west of the Buschers. The house was built in 1923. If you looked out the rear second floor bedroom window, you would be facing present-day Terrace Place. The land was still woods and homes wouldn’t be built there for another 22 years. Eddie lost his first wife, Hannah (nee Spiro) and his 9-year-old daughter Virginia, in 1924 and 1925, respectively. The newly-formed Strauss family now consisted of Eddie, his second wife Millicent, whom he married in 1925, and two children from his first marriage: 12-year-old Grace and three-year-old Daniel. Eddie’s older son, Eddie Jr., was 19 at the time and off on his own.

Millicent Meszaros was born in 1893 in the tiny farming community of Cogswell, North Dakota — one of nine children. Her parents emigrated from Hungary in 1883. Encouraged by her older brother John, a physician, she attended the Chicago College of Medicine and Surgery, and graduated in 1917. She was 24. By 1920, she was living in New York City, where the post-war flu epidemic was in full swing. Millicent worked on Randall’s Island as a physician at the Children’s Hospital, the same hospital where Eddie’s daughter, Virginia, was a patient. It is believed that the couple met there at that time.

Although the 1920 census lists Eddie as an engineer for the U.S. government, in reality he was a bookie, and Belmont Raceway was located a convenient four miles away. When Eddie first told his physician wife what he did for a living, she naively thought that he manufactured books, explained Dan, Eddie’s son, in his 2001 Valley Stream Historical Society oral history recording. The many phone lines that were installed in the Montague Street cellar belied his true profession. Eddie didn’t live long. He died of tuberculosis in 1929. In 1931, Millicent married Eddie Strauss’ best friend, Daniel Houlihan, who Dan was named after.

Millicent left the Children’s Hospital and was unable to continue practicing medicine. Dan, who self-published the memoir, “I Love You, I Said, That’s Nice, She Replied” in 1998, explained: “She tried and failed to pass the New York medical boards. I remember her studying for weeks in the upstairs back bedroom. She became a medical social worker for the Town of Hempstead instead, and a very frustrated one, because she worked for doctors, felt a lack of respect from them, and made a lot less money. This carried over into a kind of bitterness.”

Newspaper ads placed in the summer months from 1931 through 1935 promoted a school that Millicent operated in Valley Stream, most likely in her home. According to the advertisements, The Irma Park School was “a school for retarded and mentally deficient boys, requiring individual training.” Dan never mentioned the school in his memoir or in the oral history.

Dr. Millicent Meszaros Strauss Houlihan opened the Valley Stream Sanitarium in 1940 at 392 W. Merrick Rd. Her husband was employed as a wholesale hosiery salesman. When war broke out in 1942, his supply of nylon rapidly began to shrink as the military needed it to make parachutes. Houlihan took over the sanitarium’s administration. He relished his new responsibilities and was a great success, according to his son: “He loved to go over each night and talk to the patients and their families who would come to visit.” Sometime during that year, the institution changed its name from sanitarium to nursing home.

Houlihan died in December 1944 at age 50, and Millicent assumed his responsibilities. Dan, a lieutenant in the U.S. Army Tank Corps, still had two years left in the service and didn’t return to his childhood home until March 1946, with his wife Audrey and baby daughter, Colleen. Dan helped his mother run the business for six months, but mother and son were strong-willed.

“Your father wouldn’t have done it that way,” quipped Millicent in her son’s memoir. Two bosses didn’t work. Millicent handed over the building and the business to her son in 1946. There were 16 patients. In 1948, to increase occupancy, he added an extension to the back of the house, and the patient capacity grew to 26. The institution handled private and welfare patients, and many were elderly who suffered from dementia or Alzheimer’s.

Millicent remained active in the community. She was elected president of the Valley Stream Republican Club’s Women’s Auxiliary, as well as chairperson of their nominating committee. In the mid-1950s, she volunteered her time to the Long Island Hearing and Speech Society and chaired their annual Orchid Ball. In 1957, she served on the executive committee of the American Cancer Society’s Nassau division. She also loved to dance, and despite her short stature and stocky physique, she was “surprisingly accomplished and graceful,” noted Dan in his book.

Millicent’s legacy, however, and one that ultimately improved the quality of life for many Valley Streamers, was her advocacy for the founding of a local hospital. As a member of the board of directors of the Valley Stream General Hospital Committee, she received a letter from the Nassau County Medical Society endorsing the committee’s plan. The letter was reprinted, in part, in the June 12, 1950 edition of Newsday: “Your request for endorsement of a hospital in the southwest area of Nassau County has been received. It is the opinion of the executive committee of the medical society that a hospital is badly needed and they give wholehearted approval of the plans outlined.”

The location of the hospital was a different matter. The committee received a final disapproval of its plan to erect a hospital on a six-acre plot in Valley Stream State Park from Robert Moses, the state park commissioner. Moses declared that the 127-acre park was dedicated for recreational use only. It took another 13 years before a hospital was opened on Franklin Avenue, south of the Southern State Parkway.

By 1950, Dan and Audrey had five children. The roof was raised and a dormer added to the Montague house to accommodate the Houlihans’ ever-expanding family. That year, Dan started teaching sixth grade at the Wheeler Avenue School. He would later teach at Corona Avenue and Howell Road Elementary Schools. He continued to tend the nursing home at night and on weekends, and participated in various local sports. He played softball, baseball, basketball, football, punchball, tennis and ping-pong — “The only sport he didn’t like was golf — too slow for him, and it ‘interrupted a fine walk,’” daughter Colleen said in a recent e-mail exchange. Dan still played pick-up games like those he played in the many empty fields and sandlots that dotted the West End of his boyhood, as well as participated in a number of organized leagues: the Valley Stream Cubs, the American Legion Senior Division Baseball League, Mail League, St. Mary’s (Holy Name of Mary), and his favorite team of all — the West End Tavern, the local watering hole.

Dan didn’t share his stepfather’s affinity for the nursing home business. He was proficient at managing the facility — staff scheduling, food and pharmaceutical purchasing, paying bills and employees, and diligently returning all the narcotics to the county when a patient died. Staffing, however, was a particularly difficult task, scrambling to fill a shift if a nurse or aide did not show up for work. The nursing home, in time, became a burden. Dan preferred to spend his non-teaching hours with his family and playing sports. The family, which by that time had nine children and lived in a new home at 225 Dogwood Rd., moved to Stevens Point, Wisconsin in 1956.

“The nursing home was left in the care of an agent and started to fall apart at the seams,” Dan said. “The State of New York and the County of Nassau didn’t want to license it anymore unless I came back.”

The Valley Stream Nursing Home went out of business in 1961, and the property was sold. Dan and Audrey had one last child, a son, who was born in 1963, a year after the Queen Anne was torn down. Dan lived in Wisconsin as a retired journalism professor at the University of Wisconsin–Stevens Point, until his death in 2005.

Millicent also moved to Wisconsin with a dancing instructor-turned-companion before eventually settling in San Francisco, where she died in 1980.

Franklin General Hospital opened on April 1, 1963, two years after the closing of the Valley Stream Sanitarium/Nursing Home, Millicent’s vision of a hometown hospital.