Baldwinite Bruce Lister dedicated his life to others

Doris Lister says that the Bible passage that best described her husband, Bruce, is 1 Corinthians 13:4-8, a popular reading at weddings that describes love. Instead of love, though, Doris Lister used Bruce’s name: “Bruce does not boast, Bruce is not proud. Bruce is not rude. He is not self-seeking.”

The passage, she said, explained why Bruce was so willing to volunteer for Baldwin organizations, fund college scholarships at Hofstra University and do good deeds for others before he thought of himself. “Bruce did it because it was right,” Doris said.

Bruce Lister, an active Baldwin volunteer for decades, died on Feb. 4. He was 96.

“He was just a great person, and he was my best friend,” said Doris, 81. Karen Montalbano, Bruce’s former neighbor and vice president of the Baldwin Historical Society, said that Bruce was active in the community up to a few weeks before his death.

Lister was a walking encyclopedia of Baldwin history, having lived in the same Oakmere Drive house for 94 years. He was born in Brooklyn in 1922, and his family moved into the home two years later. Montalbano recalled a historical society presentation on the Heinrich brothers, who built and flew the first monoplane on land where Plaza Elementary School is now located, at which Lister stood and said, “Oh yeah, I used to play ball with them.”

“He knew so much,” Montalbano said. A former lieutenant in the U.S. Navy, Lister donated a set of hat and gloves he wore in World War II to the historical society. Montalbano’s family moved to Oakmere Drive when she was a child, and for decades she knew Lister as “Mr. Lister across the street.”

It wasn’t until she got involved in the historical society that they became friends. Montalbano’s husband, a musician, played at the Listers’ wedding. “He was always very genuine,” she said of Bruce. “He was very interested in talking with people, and always learning things.”

Lister spent hours at the First Church of Baldwin, United Methodist. On the church’s 200th anniversary in 2010, in a letter posted to the congregation’s website, he recalled a promise he made as a child to attend all regular church services — even during a blizzard that hit Baldwin on Christmas Day in the 1930s.

“My first reaction was, ‘Great, I can stay home and open all my gifts,’” he wrote, noting that no plows had cleared the road an hour before the service. “My father’s reaction was immediate: ‘You are not sick and you promised to attend! We can walk, and I’ll be with you.’ So off we went, a mile each way, through the snow drifts. A promise is a promise.”

He also wrote of organizing a live Nativity scene in 1962, a tradition that he continued for about 10 years. He was also known for making homemade jams and jellies to sell at church fundraisers.

Through his service at First Church of Baldwin, he met Doris, who was trying to find a new church with her second husband, who later died.

The two worked together on church activities, but later started meeting outside the house of worship. Doris said she was unaware at first that Bruce wanted to date her. “It took me about two years before I realized he was romantically interested in me,” she recalled with a laugh. “I guess we were dating, but I didn’t know it for some time. I just thought he was a friend.”

She eventually caught on, and the two bonded over their mutual love of music and history. Doris said she was also taken by Bruce’s desire to help others and his patience. “Bruce would always be so calm,” she said.

They were married in 1990.

Bruce attended Baldwin public schools, and went on to Lafayette College and Columbia University, where he earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees, respectively, in chemical engineering.

He served in the Pacific during World War II, and studied food technology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology after the war.

From 1943 to 1962, he worked as a research lab technician and divisional research manager for General Foods.

He then worked in various positions with Nestle Foods Corp. from 1962 to 1989, retiring as vice president of corporate affairs. At Nestle he was responsible for product development and external affairs, including government and community relations.

He was also executive director of the Tea Association of the USA, a conglomerate of officials in the tea industry.

Additionally, he was chairman of the Nassau Board of Health for more than 30 years. And he was remembered for his support of Hofstra University’s science and engineering programs.

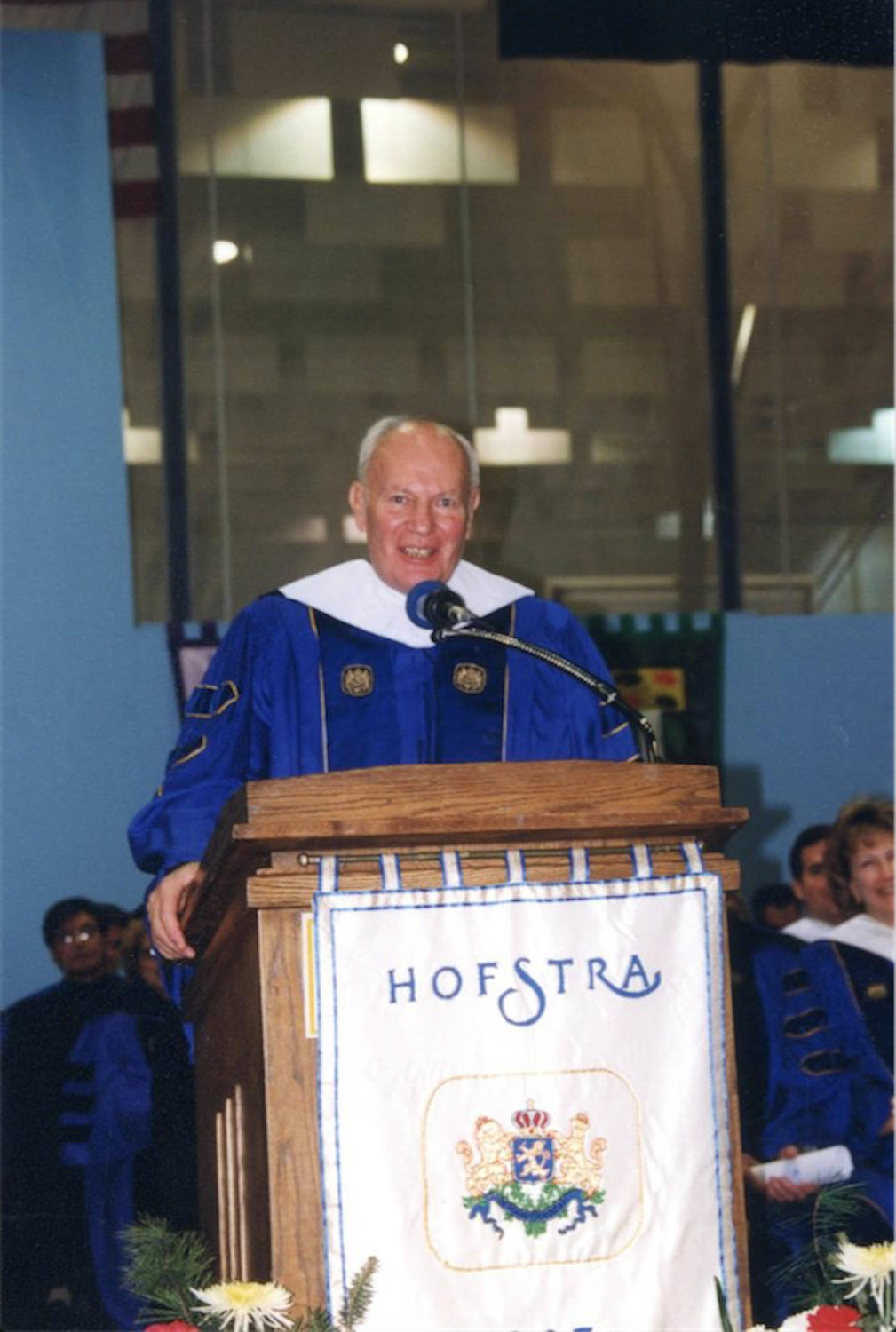

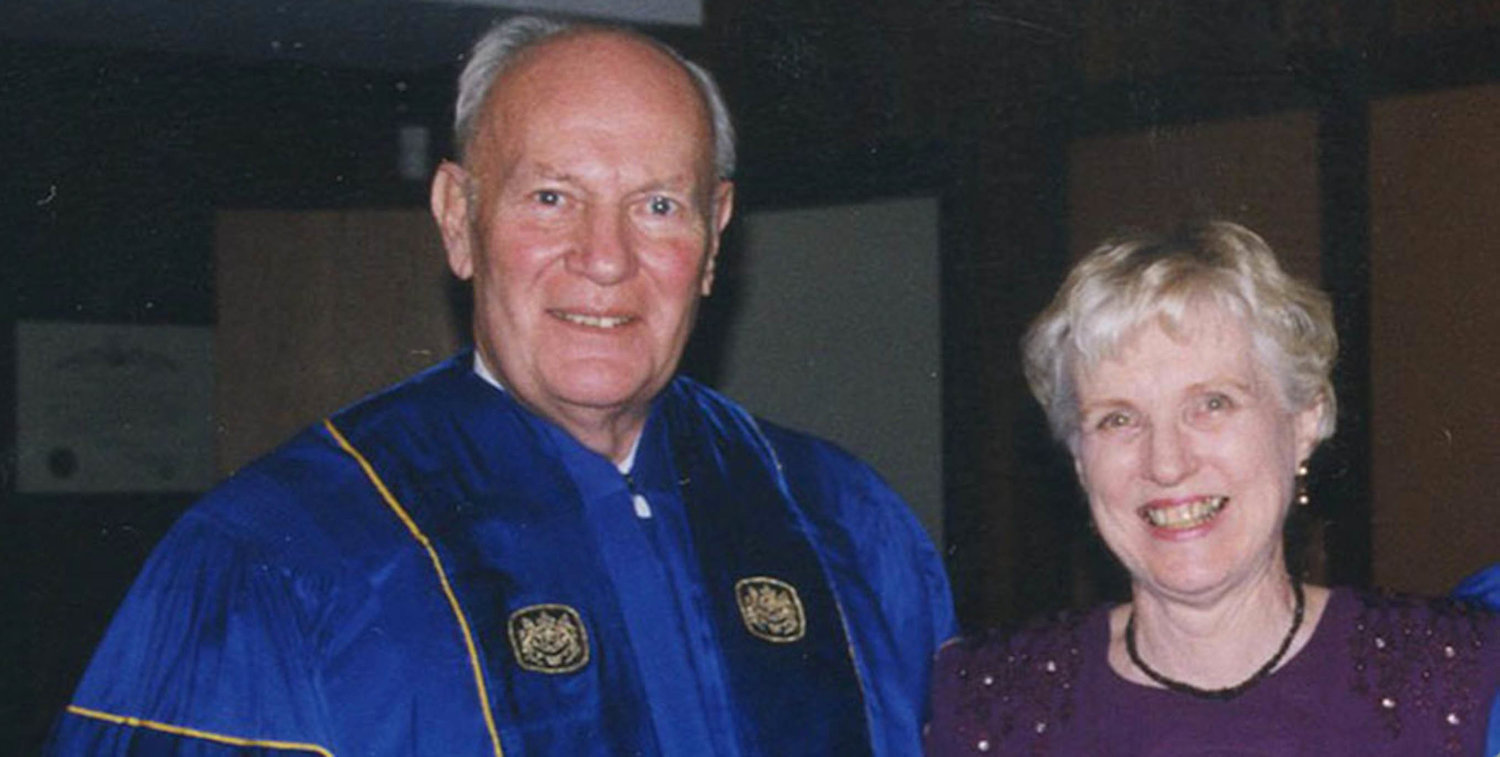

He served on the Dean’s Advisory Board of the Fred DeMatteis School of Engineering and Applied Science, and was awarded an honorary doctorate in 1988. The Listers established scholarships in chemistry, forensic science and engineering at Hofstra, and in 2014 they established the Lister Summer Fellows Program to provide students with financial assistance to spend the summer on campus conducting research in chemistry, biochemistry or forensic science.

Lecture Room 117 at Hofstra’s Herman A. Berliner Hall — home to the chemistry and physics and astronomy departments — is dedicated to Lister, who worked closely with architects during the building’s construction.

“The Listers have invested their resources, time, energy and expertise in improving the academic experience of our students and training the next generation of scientists and engineers,” Hofstra President Stuart Rabinowitz said. “Dr. Lister’s legacy lives on in the students whose research and scholarship he and his wife have helped support.”

In addition to his wife, Lister is survived by his nephews, James and Thomas Webb; and nieces, Joanne Callahan and Barbara Sinopoli. He was buried at Nassau Knolls Cemetery in Port Washington.

39.0°,

Fair

39.0°,

Fair