Faith Ringgold, seminal Black artist, on view

Library features Ringgold in online event

On Feb. 24, Mary Vahey, an art professor at Nassau Community College and Suffolk County Community College, gave a presentation, in conjunction with the Baldwin Public Library, on the artistry of Faith Ringgold, an African-American painter, writer, mixed-media sculptor and performance artist who is best known for her paintings and narrative quilts, featured in such museums as the Guggenheim and the Museum of Modern Art.

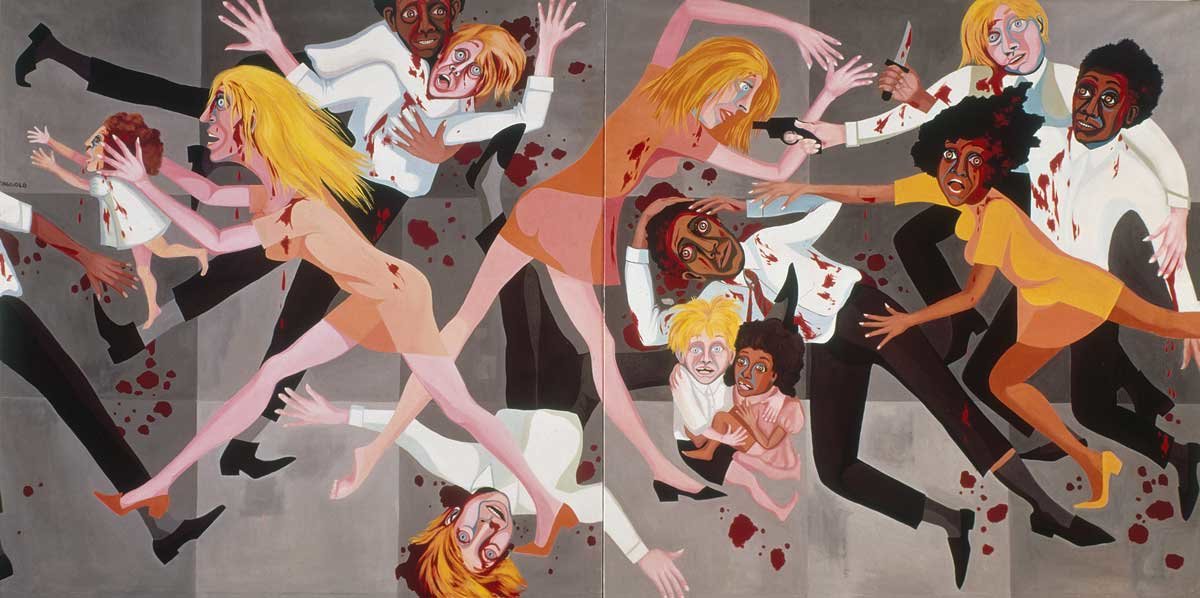

One painting Vahey focused on was Ringgold’s “Die,” from the 1967 American People Series #20. The 144- by 72-inch oil on canvas resembles Pablo Picasso’s iconic anti-Spanish war painting “Guernica.” “Die” tells a similar story of the 1960s race riots in the U.S.

In a previous interview, Ringgold, who’s now 91, said of the painting, “I became fascinated with the ability of art to document the time, place and cultural identity of the artist.” She added, “How could I, as an African American woman artist, document what was happening around me?”

Individuals’ experiences of the ’60s, however, varied dramatically, as did the reactions to Ringgold’s art. Vahey told the story of a woman who wandered into the 1969 exhibition unveiling of “Die” and, upon seeing the depiction of a melee fraught with blood and terror, “yelped and ran away.” Ringgold used the shock value of the work, as well as others that feature racial slurs, to highlight the ethnic tension and political unrest of the time.

As she broke into the art world and began to be displayed on more museum walls, Ringgold helped shed light on other artwork done by African-Americans. She played an instrumental role in the organization of protests and actions against museums that had previously neglected the work of disadvantaged groups like women as well as people of color.

Ringgold also used the traditional craft of quilt-making, which has its roots in pre-Civil War-era Southern slave culture and tell stories of the modern-day Black community as well. One of her most famous story quilts is “Tar Beach,” which depicts a family gathered on their rooftop on a hot summer night. The folk-art feel gives the work a dream-like quality, even though the subject matter is the oppressiveness of summer heat in an inner city without air conditioning. Vahey likened this “dream” to the fact that the “American dream is made up” to many Americans.

As a social activist, Ringgold continues to strive for exposure for African-American art, Vahey noted. Organizations such as Where We At, which supports African-American women artists, and Ringgold’s own foundation, Anyone Can Fly, are devoted to expanding the art canon to include artists of the African diaspora, and to introducing the African-American masters to children and adult audiences.

On Feb. 24, Mary Vahey, an art professor at Nassau Community College and Suffolk County Community College, gave a presentation, in conjunction with the Baldwin Public Library, on the artistry of Faith Ringgold, an African-American painter, writer, mixed-media sculptor and performance artist who is best known for her paintings and narrative quilts, featured in such museums as the Guggenheim and the Museum of Modern Art.

One painting Vahey focused on was Ringgold’s “Die,” from the 1967 American People Series #20. The 144- by 72-inch oil on canvas resembles Pablo Picasso’s iconic anti-Spanish war painting “Guernica.” “Die” tells a similar story of the 1960s race riots in the U.S.

In a previous interview, Ringgold, who’s now 91, said of the painting, “I became fascinated with the ability of art to document the time, place and cultural identity of the artist.” She added, “How could I, as an African American woman artist, document what was happening around me?”

Individuals’ experiences of the ’60s, however, varied dramatically, as did the reactions to Ringgold’s art. Vahey told the story of a woman who wandered into the 1969 exhibition unveiling of “Die” and, upon seeing the depiction of a melee fraught with blood and terror, “yelped and ran away.” Ringgold used the shock value of the work, as well as others that feature racial slurs, to highlight the ethnic tension and political unrest of the time.

As she broke into the art world and began to be displayed on more museum walls, Ringgold helped shed light on other artwork done by African-Americans. She played an instrumental role in the organization of protests and actions against museums that had previously neglected the work of disadvantaged groups like women as well as people of color.

Ringgold also used the traditional craft of quilt-making, which has its roots in pre-Civil War-era Southern slave culture and tell stories of the modern-day Black community as well. One of her most famous story quilts is “Tar Beach,” which depicts a family gathered on their rooftop on a hot summer night. The folk-art feel gives the work a dream-like quality, even though the subject matter is the oppressiveness of summer heat in an inner city without air conditioning. Vahey likened this “dream” to the fact that the “American dream is made up” to many Americans.

As a social activist, Ringgold continues to strive for exposure for African-American art, Vahey noted. Organizations such as Where We At, which supports African-American women artists, and Ringgold’s own foundation, Anyone Can Fly, are devoted to expanding the art canon to include artists of the African diaspora, and to introducing the African-American masters to children and adult audiences.

66.0°,

Shallow Fog

66.0°,

Shallow Fog