Fighting for tougher laws for drugged drivers

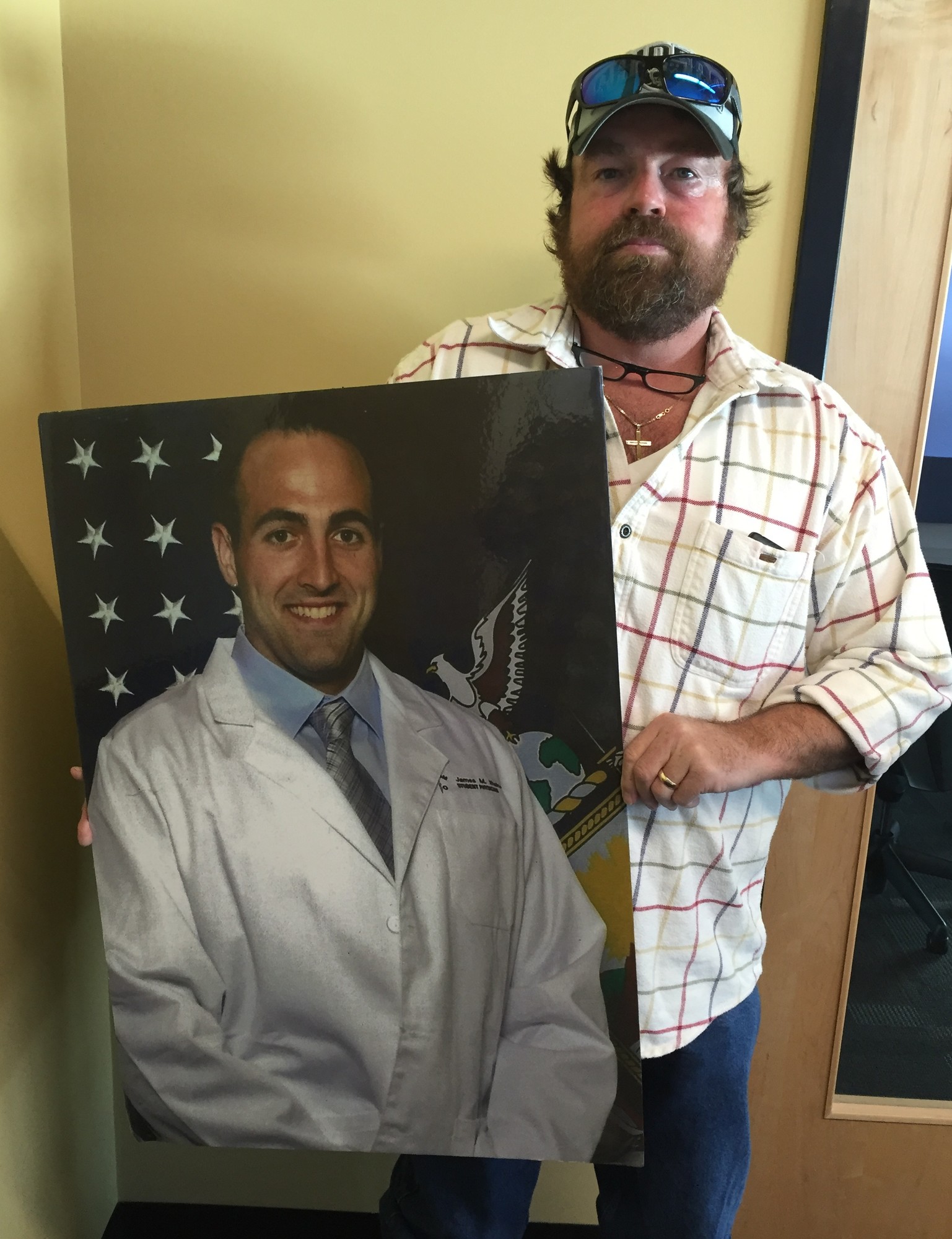

The tragedy that Philip Walker went through is one he wants no other family to experience. The Seaford resident, who lost his son in an accident in 2011, is fighting for legislation that would require mandatory blood testing for drivers involved in accidents that result in a serious injury or fatality, to determine if they were impaired by alcohol or drugs.

James Walker, a 2003 graduate of MacArthur High School and an aspiring doctor, was killed crossing the street in Brightwaters, in Suffolk County. He was struck by a 2000 Pontiac Grand Am on Oct. 16, 2011, and died five days later from his injuries. He was 26. The driver was never tested or criminally charged, although Philip Walker did win a civil judgment.

According to the police report, the drug Adderall was found in the center console of the Grand Am. The drug is typically prescribed as treatment for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD, and narcolepsy. “It wasn’t even in the prescription bottle,” Walker said as he pointed to his copy of the police report, adding that the pills were in a small plastic bag.

The absence of a more thorough investigation, according to Walker, and the lack of consequences for the driver who killed his son fuel his passion for this issue.

Walker, a 1977 graduate of Seaford High School, raised James in Levittown, and recently moved back to his hometown. His son is buried at Pinelawn Cemetery, and Walker said he visits his grave almost every day. “I’ll never have grandchildren,” he said, noting that James was his only child. “This is it for me.”

James graduated from Boston University, where he played volleyball. He then moved on to NYIT to study medicine, and was less than a year away from becoming a doctor. His picture was on the school’s promotional literature, from brochures to mouse pads. “He was their poster boy,” Walker said. “Everything the school handed out, he was on.”

At the service for him at O’Shea Funeral Home on Wantagh Avenue, there was almost a three-hour wait, his father said. There was a memorial service at NYIT as well, and Boston University’s annual alumni volleyball game has since been named in his honor.

Philip Walker is seeking legislation that would require chemical testing of a driver involved in a serious accident within two hours afterward. Bills were proposed in the State Assembly in 2013 and 2015, and similar bills have been considered in the Senate. Walker’s goal is to see a law passed in this legislative session, and he has been working with Assemblyman Michael Benedetto (R-Bronx) to accomplish that.

“I can’t bring my son back,” Walker said. “I can’t do anything to put [the driver] behind bars. What I want to do is have it so people don’t have to go through what I went through. How many more people have to suffer?”

He sad that he sees people driving under the influence of prescription drugs as a growing problem, one that mirrors the epidemic of drinking and driving before tougher laws were enacted.

He cited the establishment and subsequent advocacy efforts of Mothers Against Drunk Driving, which forced the country to take the issue seriously. “Only because of them speaking out, the law was changed,” he said. “I’m basically trying to copy what they did and trying to achieve their magnificent results. In my case, it’s people who are using drugs.”

Struggle for legislation

Getting the law passed is hardly a simple process. Benedetto said that similar laws have been enacted in other states, only to be struck down in court as unconstitutional. He explained that forcing someone to take a blood test was ruled to be a form of self-incrimination.

In the Senate, the lead sponsor was John Flanagan. Benedetto said that the Senate and Assembly never reached an agreement. With Flanagan now the Senate majority leader, Benedetto is trying to find a partner in the Senate to sponsor a bill that would achieve his desired outcome and address the constitutionality issues. He added that if someone dies as a result of an accident caused by a driver’s impairment, the driver should be punished.

“There should be a way to give some form of justice in this particular area to the deceased and certainly also to the families,” Benedetto said. “People should not be out there driving if they’re … impaired by a drink, if they’re impaired by drugs. You’re putting the lives of other people at risk. There’s got to be some way we can figure out how to do this legally.”

The first bill was introduced several years ago by a now former assemblyman, according to Benedetto. He took up sponsorship after getting a call from a woman who lost her husband in similar circumstances.

“It’s a terrible tragedy,” he said of Walker’s losing his son. He added that he doesn’t want a “watered down” bill, and admitted that earlier versions of it were, giving the driver the option to refuse a blood test.

“There’s got to be some way we can figure out how to do this legally,” Benedetto added, expressing his hope that a solution exists that would pass “constitutional muster.”

New York has similar laws on the books for driving while intoxicated. Current state law requires a driver arrested for DWI to take a blood, breath, urine or saliva test, and a refusal to do so means a one-year suspension of a driver’s license if the police have probable cause. A person who refuses a test following an incident that results in serious injury or death can be forced to take a sobriety test only after a court order is obtained.

October will mark five years since James Walker’s death, and his father said that his “realistic and reasonable” goal was to see legislation passed within five years. “I just want the law passed,” he said, “and if they name it after my son, that would be the cherry on top.”

Educating others

Kevin Weiss, a friend and volleyball teammate of James’s at BU, is supporting Walker’s efforts. With Walker looking to establish his own nonprofit group, Weiss and other friends of his son are looking to help Walker find the right people to support his efforts, such as those who can provide technical expertise in creating a website.

“Phil is still living this daily,” Weiss said. “That’s my hope, that he finds the right people to help him.”

Weiss said he has encouraged Walker to find other people who have dealt with similar tragedies, and to work with them in his advocacy efforts. “To create change,” Weiss said, “you need to rally around a common cause that has many faces and many stories.”

He agreed with Walker that driving while under the influence of prescription drugs is a growing problem that “I don’t think we’ve responded to really well as a society.” The shock of James’s life cut short still resonates with him.

Walker said that in addition to advocating for changes to the law, he would like to bring educational programs to local schools, specifically at the middle school and high school levels. “I want to let them know the effects,” he said.

James was planning to work in an emergency room for his first year after graduating from medical school before becoming a surgeon. NYIT awards a scholarship every year to a male medical student with a strong community service record and a desire to work in an ER. Walker attends the hooding ceremony each year, in which the graduates officially become doctors.

“James, he would help everybody,” his father said. “You couldn’t ask for a better son.”

65.0°,

Mostly Cloudy and Windy

65.0°,

Mostly Cloudy and Windy