Trying to preserve the village’s history

“Every time I used to come out by Lenox Avenue, I’d see that house, and I’d think, what a shame that it’s deteriorating.”

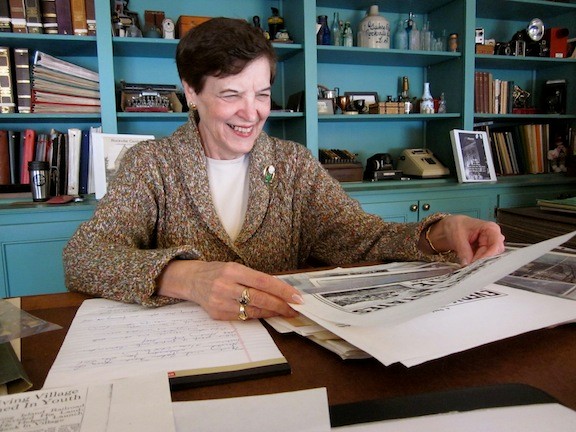

Marilyn Devlin, a longtime village resident and the archivist at the Phillips House Museum, pored over an aging photograph of a Rockville Centre home dating back to the turn of the 20th century. The dilapidated house still stands at 21-31 Davison Place, but not for long — a developer intends to tear it down and replace it with three new neo-Colonial homes.

At the Jan. 13 village Board of Trustees meeting, roughly a dozen residents from the neighborhood turned up in the hope of saving the house, only to find out that it was likely too late — the new plans had been finalized and the exterior designs of each of the new homes were due to be approved that night. After a number of speakers, including former Trustee Jeanne Mulry, argued for the importance of preservation, the group left the room resignedly, aware that it was only a matter of time before the house would be demolished.

In the days afterward, Mitch Levy, a village resident and one of the most outspoken of the protesters, was allowed a short tour of the house. “Let me tell you, there really is very little of it left,” he said. “There’s not one architectural detail. No sink, no toilet bowl, no mantle. It’s all completely removed.”

Levy loves history. A member of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, he collects antiques and frequents auctions — his own home, on South Marion Place, dates back to 1899, and he has furnished it almost entirely with period furniture and décor. “I’m a purist,” he said. “I don’t want it to look sleek and new. So I try to stay away from anything that’s plastic or aluminum.”

Levy had hoped to buy the Davison Place house, which is part of a huge estate that sits on two lots that have nearly an acre of land, and refurbish it himself. But he was unaware, he said, that the house was even for sale until contractors removed all the vegetation on the property on Christmas Eve.

And, Levy said, the cost of purchasing the house and making it livable would be far too high. “If you walk through this house, you see you’re not really buying anything,” he said. “You’re buying a piece of history.”

The home itself likely dates back to before the 1890s, although village records from the period, Devlin said, are far from complete. In 1895, the estate was owned by a woman named A.A. Osborne; the next owner on record, listed in the 1907-08 phone book, was John W. Holmes, and 15 years later the home had yet another owner. Devlin recalled that for a time in the 1970s and ’80s, it was a rooming house. “We used to see a lot of gentlemen hanging around there who were not that well-off-looking,” she laughed.

In the 1990s the house fell into disrepair, and Levy recalled a number of children breaking in and causing trouble — a man on South Marion was the foster father to around nine children, he said, and he would let them run amok.

Devlin, who wrote “A Brief History of Rockville Centre: The Heritage and History of a Village,” said that it’s possible that before Osborne’s ownership, the house belonged to, or was built by, the Davison family. The head of the family during that period, John T. Davison, was a postmaster, a banker and a local real estate mogul of pioneer stock. He was a charter member of the Bank of Rockville Centre Trust Company and one of the earliest village trustees, who helped to oversee the installation of electric lights and the construction of the water plant. His family also owned the Davison Mill and Davison Shipyard in East Rockaway.

Davison is best remembered, however, as the “Father of Park Avenue.” As the head of the South Side Realty Company, he built hundreds of residential and a number of commercial buildings in the village, some of which still line Park Avenue today. Devlin said it is likely that Davison Place is named after him — and also that he built most of the historic houses on that block.

Rockville Centre is full of historic homes. Morris Avenue has a number of them, including one that belonged to former Mayor Edwin G. Wright, and State Sen. Dean Skelos used to live in the Anthony and Phoebe DeMott house on Hempstead Avenue. Devlin lives in one of a number of “catalogue houses” built in the 1920s by companies like Sears, Roebuck and Montgomery Ward; property owners would build a foundation and select a style from a catalogue, and companies would send all the needed parts, from the lumber to the nails, to the building site via railroad. Several of the houses still stand on Powell Avenue.

Preservationists wonder, then, why the village does so little to save these buildings. “A lot of people do ask about their homes and the history of their homes,” said Devlin. “If we could get it out there and just have people contact us.”

Devlin said she believes that if a preservation committee were formed, it would flourish, populated by history buffs and fans of the old-time residential feel of traditional Colonial- and Victorian-style homes. Any who are interested, she added, should call the Phillips House at 678-9201.

“The track of history is very important, to know where we started and where we’ve come,” Levy said. “I think it’s important that the village take an active role in trying to maintain the flavor of the village. Otherwise it’s going to become another type of village.”

Levy later added that although homes like the one at 21-31 Davison Place do need work, the fact that they still stand today is a testament to their quality. “Even in its poorest conditions, that house has stood from 1895,” he said. “The house was built to last, and it has. As much as it’s been beat on.”

A few days after the Jan. 13 board meeting, Mayor Francis Murray made it clear that he took the call for preservation seriously. He called Dan Casella, the village’s building superintendent, and asked to see if the owner of the Davison Place property would grant a stay on demolition. The home promptly went on the market for $700,000. Shortly afterward, Levy took his tour of the building, and found himself wishing he had done so years before.

“I could have looked at that old house, even when it was in poor conditions, and I could have seen potential,” he said.

50.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

50.0°,

Mostly Cloudy