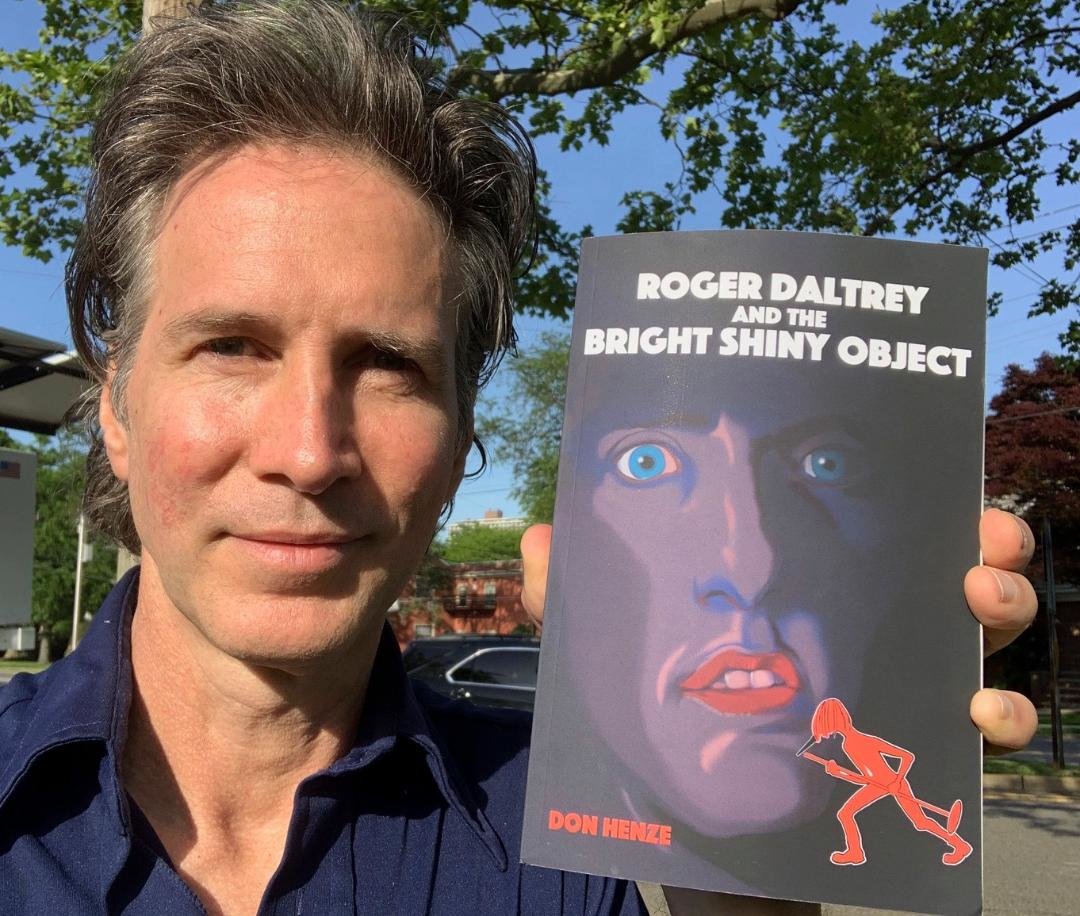

Former Baldwinite writes book on music industry experience

Aspiring star became a ‘bright, shiny object’

Don Henze comes from a musical family: His father, Don, was in the band Curt Jensen with the Don Henze Rhythmaires and played on American Bandstand. His grandfather Phil Henze played banjo at various live venues. His great-great-grandfather Otto, who emigrated from Hamburg, Germany, played upright bass at Carnegie Hall in the 1900s until his death in 1916 from syphilis due to ‘fooling around’ with the Hippodrome showgirls. So when Henze (pronounced HEN-zee), 58, was going to Baldwin High School, he knew his destiny was a musical one.

When he met up with Roger Daltrey, lead singer and songwriter of the Who, it altered the course of his life. Accounts of the highs and lows of that experience can be found in Henze’s self-published new book, “Roger Daltrey and the Bright Shiny Object,” out now.

“For me, the music thing started long before I was even born,” Henze said. “It was inevitable. It was instilled in me by my father to be a famous musician from the age of 4, when I started taking lessons from him.”

There was something of an unofficial curse in his family that once you got to the top, your time was up. His grandfather played so hard in 1978 on stage at a family reuion that he died of a heart attack three minutes after finishing his set, nearly fullfilling his goal of dying like his idol Eddie Peabody-a famous banjo player who is said to have died playing the banjo. “I was there,” said Henze, who was 14 at the time. “I saw the whole thing. [People] kept screaming, ‘One more song!’ ‘One more song!’ and he was struggling and struggling — his face was beet-red.” “So both (great grandfather and grandfather) died as a direct or somewhat direct result of being muscians,” said Henze.

But Henze’s father wasn’t deterred from a music career, and neither was Don Jr. He started a band called Radio Stupid when he was 26, and began playing shows with the hope of being discovered. Gerard McMahon, who was writing songs with Carly Simon at the time, heard Henze sing. “He took an interest in me philosophically,” Henze recalled. “Musicians on that level, they take you out to dinner, you drink fine wine and they reach into your heart and soul before they ever hear you play.”

Recognizing Henze’s raw talent, McMahon offered him a spot as a drummer in his self-named band, Gerard McMahon, which was Henze’s perceived “in” into the industry. From then on he played shows with McMahon — until a year later, when he met Daltrey.

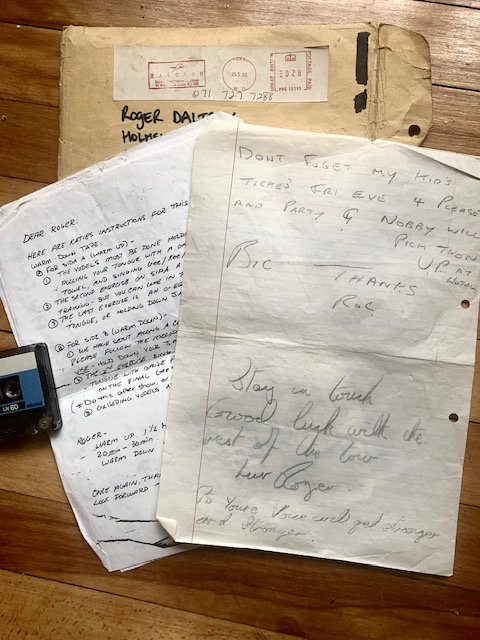

“Roger hired Gerard to produce and write his solo record ‘Rocks in the Head,’” Henze recounted, “and Gerard said, ‘Don, you’re gonna play drums for Roger.’” That was when things got particularly interesting for Henze, but he said it’s hard to capture everything that transpired without all the nuances in his book. He frequented the famed Abbey Road recording studios in London with Daltrey as he worked on the solo album, on which Henze is credited with backing vocals.

Daltrey was slated to manage Henze’s band Radio Stupid, but they never signed a contract, and Henze played on occasion and worked other jobs while Daltrey moved on to managing other bands. Their briefly intersecting lives as musicians is summed up in the title of Henze’s book — a focus on something that is new, current or trendy, until something new comes along. “I was the bright shiny object,” Henze said, “in Roger and his family’s world.”

41.0°,

Fair

41.0°,

Fair