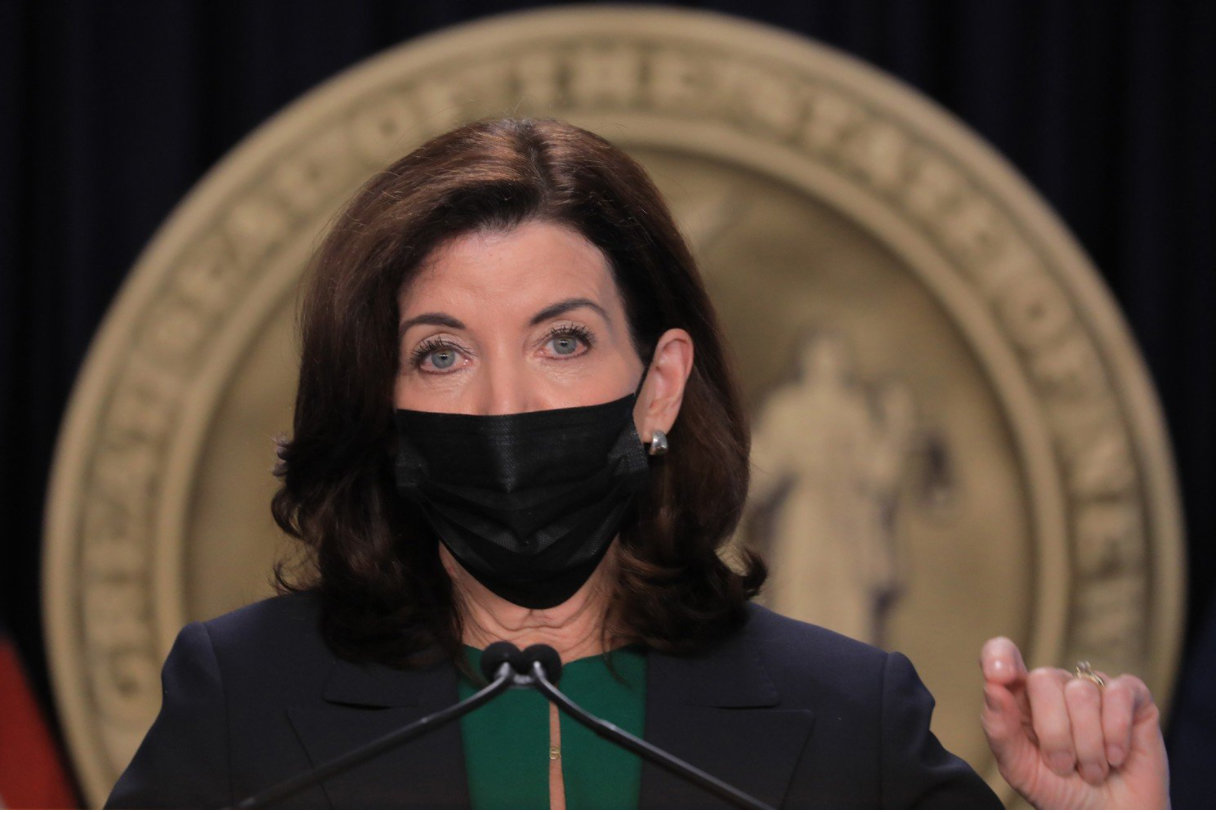

Hochul rolls back housing proposal amid backlash

Gov. Kathy Hochul pulled her proposed zonning plan in her New York State 2022-23 budget that would require local governments to allow an expansion of apartments in single-family neighborhoods. Local leaders who were protesting Gov. Kathy Hochul’s proposal, rejoiced on Feb. 18 outside of an East Meadow home, a day after the plan was dropped from the budget.

The provision would have directed local municipalities to adopt local laws allowing for accessory dwelling units, known as ADUs, and make it harder for local government to block their development.

Officials and critics argued that the measure would take considerable zoning power away from local governing boards. At a news conference earlier this month, County Executive Bruce Blakeman said, “It’s an attack on the suburbs — it’s an attack on the suburban way of living…This is a power grab from New York City politicians, and we’re not taking it.”

Local leaders pointed out the potential detriment an expansion of ADUs may have on residential neighborhoods, including an increase in traffic, a strain on resources and infrastructure, overcrowding of public schools and overdevelopment.

Valley Stream Mayor Edwin Fare expressed his concerns on social media, urging residents to make their objections heard in Albany.

“By allowing an explosion of additional housing in our village, the state would put Valley Stream at enormous risk for fire and public safety emergencies,” the mayor said. “Our population could double in a blink of an eye, and the potential for disaster is very real.”

Hochul argued that ADU expansion may be the state’s first crack at tackling New York’s affordable housing woes, which have only intensified in recent years.

Lawrence Levy, dean of Hofstra’s National Center for Suburban Studies, said that “accessory dwelling units are one of several answers to the shortage of affordable housing” because it gives an opportunity for homeowners to “get a little more revenue pinched by the high cost of property taxes.” ADUs can provide an affordable living option for young people and help older adults on fixed incomes stay in their homes, he said.

The practice of homeowners discreetly renting out parts of their homes is already taking place in neighborhoods across Nassau County, according to Levy. There are already dozens of illegal, unregulated apartments “where the people who are renting them don’t have the protection if they were otherwise inspected for fire and other codes, and homeowners are constantly looking over their shoulder afraid that they’re going to get caught for doing something that’s not allowed,” Levy said.

Levy added that the frustration of many advocates is that too many municipalities haven’t been willing to incorporate AUDs as a legitimate part of the housing mix. A sensible public policy, however, should still “respect the ability of local officials to control [the growth of ADUs] so that neighborhoods aren’t overrun and living in unsafe conditions,” he said.

Meanwhile, with soaring housing costs and the price of rental apartments not faring that much better, finding affordable housing options in the village has been “tough,” according to Thomas Dowling, a licensed real estate salesman at Exp Realty. Much of the frustration can be traced to the available supply of houses not keeping up with the high demand, a housing phenomenon seen across Long Island.

“[The cost of owning a home] certainly has changed over the years,” Dowling said. “Ten years ago in 2012, the average Valley Stream home was $362,000. Fast forward five years to 2017, the average is $456,000. Over the course of five years, homes appreciated in Valley Stream roughly $100,000.”

The pandemic has exacerbated that imbalance even more. In January of 2020, the average home in Valley Stream was $523,000, as compared to around $619,000 in January 2022. Over a 10-year period, housing prices have doubled in value in Valley Stream, which is not typical, officials said.

For those who rent an apartment, Dowling said that the situation isn’t much better. “The challenge with the rentals is the same challenge we’re having with purchasing homes: it’s a pricing issue as well,” he said. “There are 20 publicly listed apartments, six of them are under $2,000. Five are between $2,000 and $3,000. And there are nine units that are between $3,000 and $5,500. When you consider that people are spending $2,000 to $3,000 to rent, that’s a mortgage payment. If the goal is to bring a more affordable [housing] option to Valley Stream, there doesn’t appear to be an affordable option.

“In a healthy market, you’ll have a mix of different sorts of homes: single- or two-family homes, rentals, condos and co-ops,” said Dowling. “A diversity of types of housing is healthy…”

Valley Stream officials have recently added a number of new high-density, multi-family apartments to the village. But the village has hardly budged in responding to requests both by residents and the Nassau County Planning Commission to ensure new apartment projects comply with the affordable housing provisions, mainly the decades-old Long Island Workforce Housing Act – intended to help middle-income workers like police officers and teachers with their housing needs, critics have said.

The act mandates that local governments require developers proposing housing projects that include five or more residential units to either set aside 10 percent of the units in a given project for the workforce or affordable housing; construct workforce housing at another site within the same municipality; or pay a fee for each affordable unit the developer would have been required to construct.

Local governments are responsible for enforcing the requirements of the act.

39.0°,

Fair

39.0°,

Fair