Locals remember Seaford teacher, historian, naturalist

Basil Northam’s legacy to live on in Seaford

Basil Northam, who taught special education at Seaford High School when the field was in its infancy, died on Dec. 27 at his home in Southold. He was 89. Northam devoted his life to studying the poet Walt Whitman and Long Island’s native and natural history.

Bruce Northam, a travel writer and one of Basil’s three sons, recalled his father as a true naturalist, with binoculars and hand lenses at the ready, and a man who was enthralled with existential philosophy.

“We always had a copy of ‘Leaves of Grass’ around the house,” Bruce said. “It was our coffee table book.”

Northam received degrees from Emerson, Adelphi and Hofstra, and retired from teaching at age 55.

Steve Bongiovi, secretary of the Seaford Historical Society and a former Seaford High English teacher, said he knew Northam only briefly, because they taught in different departments at different times. Bongiovi added, however, that Northam was renowned throughout the building as Seaford’s special education program pioneer. He usually taught eight to 10 children with emotional or physical challenges.

“He was a remarkable man,” Bongiovi said. “Patient, kind, understanding and a great colleague.”

He was also the go-to guy for conversations about Long Island’s natural history during his tenure, Bongiovi said, adding, “I’ve only begun to appreciate now, as a member of the historical society, how much he knew and what he did.”

Researching L.I.’s Native American history

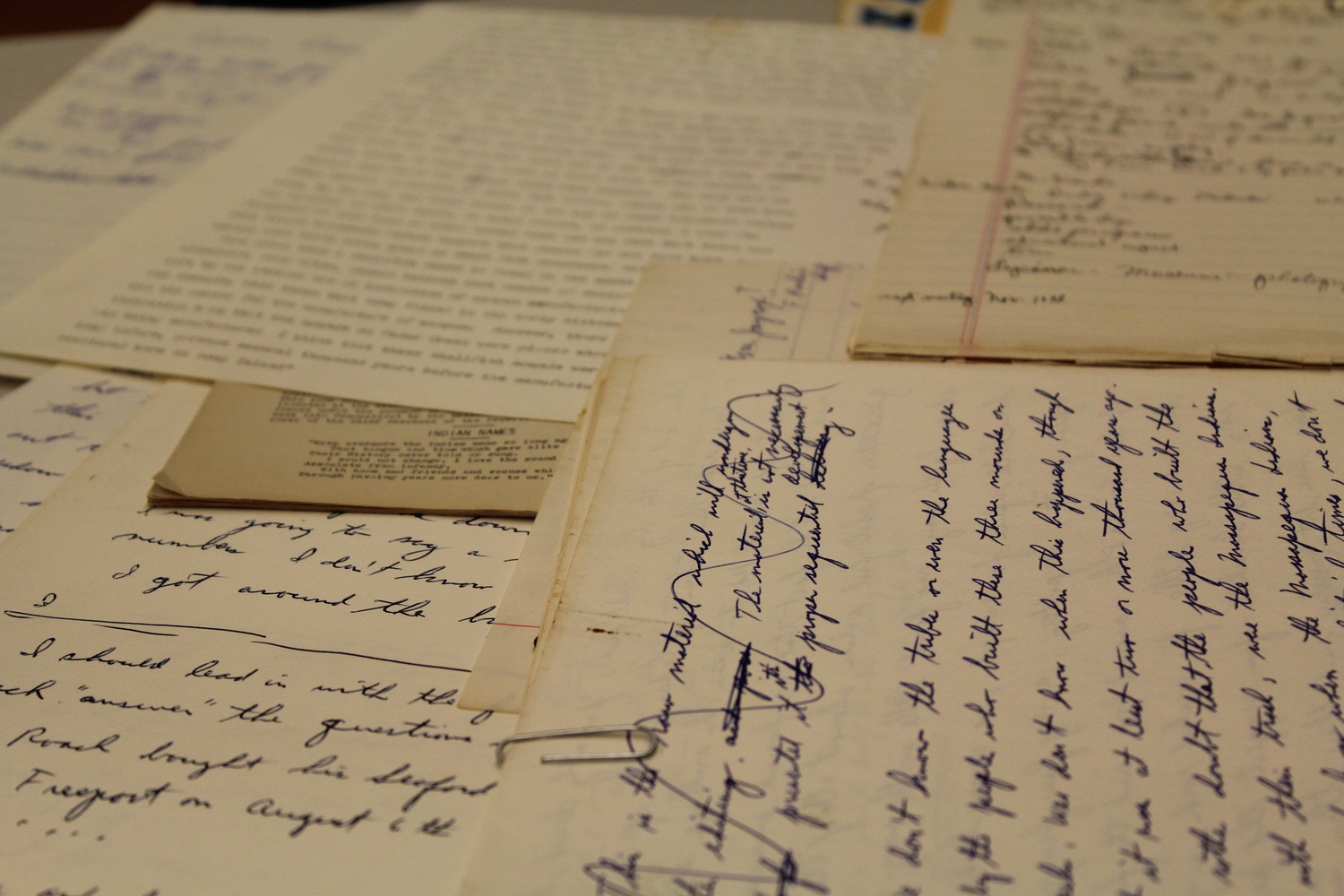

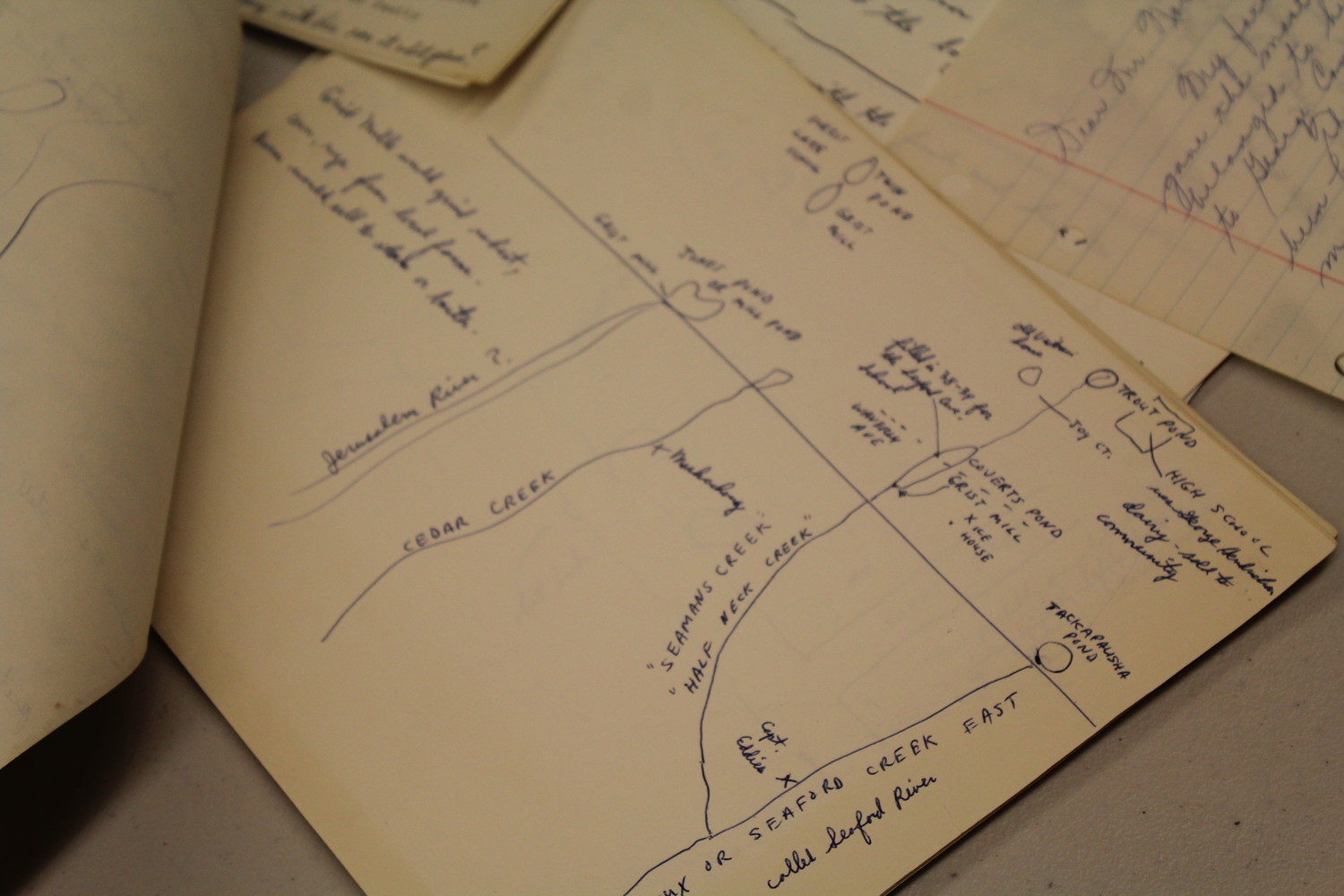

Toward the end of Northam’s life, the historical society came across a packet of his notes, maps and documents. With them, members of the organization learned more about Native American history on Long Island, including the location of shell banks in the area, as well as Chief Tackapausha’s burial location.

“His knowledge that he passed on about the Native American population was very revealing,” Bongiovi said. “He implies, or at least surmises, that it actually goes back thousands of years in this region.”

Northam wrote that the area that is now Seaford was used as a manufacturing site for wampum, the currency used by Native American tribes. There they collected shellfish, cooked them for food and saved the shells, which became wampum. Bruce recalled that his father knew where Native Americans used to live on Long Island, and unearthed artifacts that he brought home and into his classroom.

“We always had arrowheads all over the house,” Bruce said.

Helping preserve Whitman’s legacy

Before the Walt Whitman Birthplace Historical Site was founded, Bruce said, his father was captivated by the work of Whitman and other transcendentalists such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau.

“When my dad was at Hofstra,” Bruce said, “he heard that they were going to demolish the birthplace, and he went door to door in order to save it. That led him to being a trustee at the Birthplace Association.”

Bruce also described his father’s love for Jayne’s Hill — one of Whitman’s favorite locales, in Suffolk County’s West Hills — ever since his father went there with his parents for a family outing in the mid-1930s. It was where Basil proposed to his wife, Johanna, and where he affixed a plaque to a boulder inscribed with a tribute to Whitman.

“The day that the Vietnam War ended,” Bruce added, “because my father was tortured by it, like every liberal, left-leaning person at the time, he packed his sleeping bag and went to spend the night on Jayne’s Hill.”

Ultimately, his father was one of the reasons why Bruce took up travel writing, and his latest book, “The Directions to Happiness: A 135-Country Quest for Life Lessons,” includes several anecdotes and lessons from his father.

"My father taught me that you don’t have to fly halfway around the world to have a travel experience,” Bruce said.

A man who made Seaford history

Although Northam’s notes on Seaford and his contributions to the Walt Whitman site are well documented, there is one piece of his work that the historical society has yet to discover: a film titled “The History of Seaford.”

In the film, according to his notes, Northam interviewed several of the hamlet’s oldest residents at the time. He noted that he gave a copy of the film to the Long Island Studies Institute in the early 1970s.

“I have so much ‘junk,’” he wrote, “that it is beginning to overwhelm me and I never use a computer. I have tapes and I have tapes.”

Asked about the film, Johanna Northam said her husband had given a copy to an unknown Seaford resident. But the historical society has yet to find a copy of it, which Bongiovi said was a testament to Basil’s legacy as a natural historian.

“Even in creating that film, he showed a deep, abiding love of Seaford,” Bongiovi said, “and left a legacy that we would love to cherish, extend and offer to the current generation.”

Despite the fact that the film’s whereabouts are unknown, Bongiovi said he believed Northam had made great contributions to the historical society’s work. Bongiovi said he envisioned a special rotating display in the society’s museum, with one exhibition dedicated to Northam’s research.

Bruce Northam said he was thrilled to find out about this potential plan. “I think it would be an incredible tribute to my father, because his main goal in life was to make the world a better place,” he said, “and Long Island was the place he knew best.”