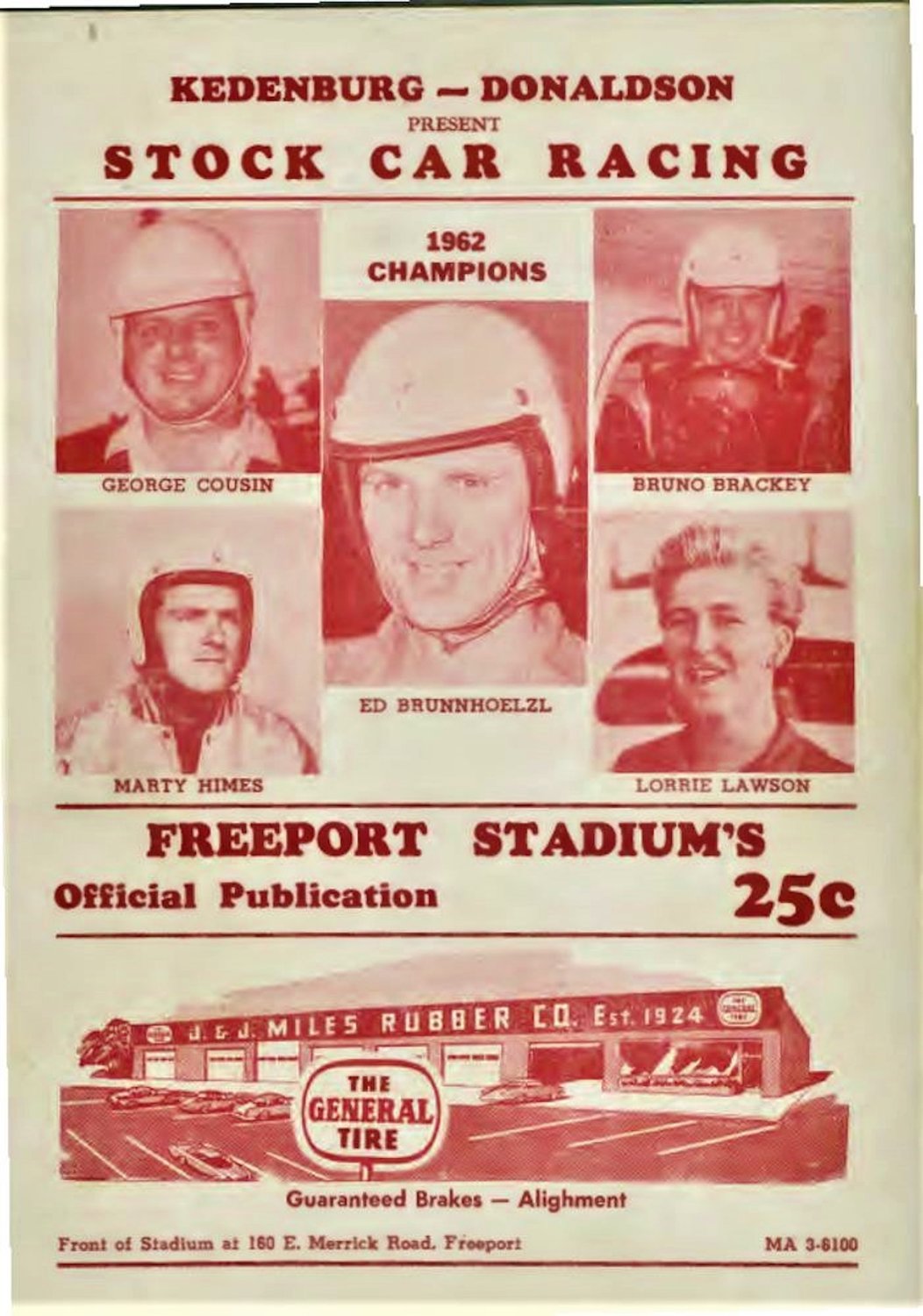

Race car champ donates memorabilia to museum

Freeport’s Marty Himes sends historic items home

When Marty Himes was growing up at 61 Hanse Ave. in Freeport, his proximity to the Freeport Municipal Stadium put him on track — pun intended — for his lifelong career: racing cars.

The event that hooked Himes was a humble soapbox derby.

“In 1952,” said Himes, now 82, in a recent interview, “I pushed my brother Reggie around the stadium while he steered with a rope.” They painted 777 on their wooden soapbox car.

Himes went on to a career that included a championship at the stadium 10 years later (see breakout box), honors at raceways from Riverhead to Pennsylvania to Connecticut, and photo ops with the likes of Guy Lombardo and Mickey Rooney.

Early on, Himes had the foresight to do a rare thing: in 1975, while still actively racing, he established the Himes Museum of Motor Racing Nostalgia on his own property in Bay Shore. He had bought the property the same way he had lived his life: He saw an opportunity and pounced.

“I had no complaints — I enjoyed my life in Freeport,” he said. “But the time came and I picked up on the opportunity. This house was $10,990. I saw it on the cover of a newspaper, a picture the size of a business card, and I said, I’ve got to have it, there’s a porch and the whole thing. That was in ’65. I bought it instantly and I’m still here.”

With his wife, Violet — “Everyone called her ‘Red’ because she had red hair,” said Himes — he moved to Bay Shore, but he wasn’t so much moving away from Freeport as he was bringing his Freeport racing enthusiasm to his new house.

He continued the life he had built in Freeport — working various jobs and finding sponsors to support his racing career. In his youth, he had worked for people like Bill Schindler, “Freeport’s famous one-legged chauffeur,” to quote from a 1952 Leader article. “Bill came to the track on crutches, but he won over and over,” Himes said.

He also financed his races with sponsorships.

$50 bought you an engine

“You always had a sponsor, even if it was just a grocery store or an auto supply store,” Himes said. “Liberty Electric Supply Company in Farmingdale sponsored me for several years. I put their ad on both sides of my race cars, every car I had, and it was free advertising for them in return for footing the bill.”

But the expenses of having cars to race — and Himes raced Tuesdays, Fridays, and Saturdays, and some Sundays, at Freeport Municipal Stadium — were also paid in sweat equity, as Himes’s friend Sam Pardo explained.

“These young guys would get an old car with a decent engine from a junkyard for 50 bucks,” Pardo said. “They took all the glass out, maybe put in a roll cage, and tweaked the engine to make it faster. You had different classes. ‘Bomber’ was your basic class, and other classes went up from there. It was a very accessible sport back then, not like today, when a race car costs thousands of dollars.”

“The more we knew about each car, the less the expense,” Himes said. “We did it all ourselves. I used to work on my cars at 103 Mill Road where Buffalo Avenue comes out. I raced four or five of my own cars a night. We raced 20 to 30 cars at a time, depending on the event.”

The drivers would arrive with their cars to the pit area around 2:30 p.m., ready their vehicles, and race from 7 to 10:30 p.m.

“There might be a special event, like a 100-lap race instead of 35 laps,” Himes said. “The winners got big money. I had a great time, a great career, and I knew everybody.”

But Himes could see the handwriting on the wall early in the 1970s. Even while he was still racing, and publishing magazine articles about Freeport Stadium and the Mineola Fair, he was watching the 40-plus race tracks on Long Island start to price themselves out of business. Race track fees, always an issue even when the nightly entrance fee was just $4 per driver, rose steeply, as did the price of engines and wheels. Eventually, only drivers with big-name sponsors at big-name tracks could go on.

Freeport Municipal Stadium, which once sat between Albany and Buffalo avenues on the site now occupied by BJ’s, had hosted every sort of sports and entertainment since it opened in 1931. But according to a September 1949 issue of the Leader, the only real profit-maker was racing, especially once midget-car racing became popular in the 1940s. As racing changed, so did the stadium’s finances. It closed in 1983.

By then, the Himes Museum of Motor Racing Memorabilia was making a name for itself. Himes had started with his own 1937 Fords, 1937 Plymouths, the Schwinn bike he had earned from Sam’s Bicycle Shop in the 1950s with its $86.95 price tag still on it, and soapbox derby car 777. He had acquired racing helmets from other drivers, midget cars, a 1956 Ford, artifacts from the Vanderbilt Cup races that made Long Island world-famous for motor racing, and memorabilia from such drivers as Freeport’s own midget car champion, Johnny Coy.

With the same direct action that had impelled his own career, Himes tackled the preservation of artifacts from the Freeport Stadium when it closed. Knowing that everything in the stadium was destined for destruction, he didn’t always wait for the village bureaucracy to grant permission.

“He used to say, ‘The blue torch cuts the red tape very easily,’” Sam Pardo said.

“I took the 27-foot flagpole down myself,” Himes said. “It’s lying in my driveway on blocks.” He also acquired the three-foot-high letters from the outer stadium wall that read “Freeport Municipal Stadium,” two turnstiles from the entrance gate, two ticket booths, and smaller items such as one of the original checkered start/finish flags. Nobody in the village government ever protested.

History comes home

Now, some of these artifacts have come back home to Freeport. Himes, a life member of the Freeport Historical Society who used to cut the museum’s grass and help scan historical photos, has donated the stadium letters, one of the turnstiles, one of his own racing jumpsuits, a checkered flag, a sidewalk sign that once stood outside the stadium advertising the races, a jacket from the Rod Snappers auto club that existed in Freeport in the 1950s and numerous other items to the Freeport Historical Museum at 350 S. Main St.

The items were transported from Bay Shore to the museum on a Jack’s Home Services truck owned by contractor Jack Sandhaas, assisted by Freeport Historical Society Trustee Denise Rushton.

The one item that hasn’t made it back to the museum’s yard yet is one of the two toll booths, which will require use of a flatbed truck.

“History is returning to Freeport,” Pardo said. “This is where these items belong. Through the generosity and foresight of Marty Himes, the two museums are working together to preserve a big part of Freeport’s past.”

Anyone wishing to volunteer to help move the toll booth, or visitors interested in the voluminous historical artifacts at both museums, can contact the Freeport Historical Society and Museum at (516) 623-9632 or FHS@freeporthistorymuseum.org. The Himes Museum of Motor Nostalgia, at 15 O’Neil Ave. in Bay Shore, can be contacted by calling Marty HImes at (631) 666-4912.

44.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

44.0°,

Mostly Cloudy