Remembering a church visit by John Lewis

Glen Covers were honored to meet Lewis

Six years ago, U.S. Rep. John Lewis, the late civil rights leader, spoke at First Baptist Church of Glen Cove on a Sunday and signed copies of his 1998 memoir, “Walking With the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement.”

According to the church’s pastor, the Rev. Roger Williams, then U.S. Rep. Steve Israel, whose 3rd Congressional District included Glen Cove, reached out to Lewis to ask if he could visit the church.

“I told him certainly it was going to be an honor,” Williams recalled. “He came with Steve Israel and one of Steve Israel’s aides at the time, and people from all over the community were here . . . the people that were here, you could tell, were profoundly respectful of who he was and his living legacy. They knew who he was; they knew he was a major exponent of the civil rights movement. It was Black and white here that day to see him. They knew they were in the presence of civil rights royalty.”

Williams remembered seeing Lewis many times before meeting him. He had seen photos and videos of Lewis on television and in newspapers and books recounting his fight for civil rights.

As detailed in Lewis’s congressional biography, as a college student at Fisk University in Nashville, Tenn., he demonstrated in sit-ins at segregated lunch counters in 1961, and took part in Freedom Rides, which challenged the segregation at bus terminals across the South, often risking his life just for sitting in a seat reserved for white patrons.

By 1963, Lewis had become a national leader of the civil rights movement. At age 23, he was an organizer and keynote speaker at the 1963 March on Washington.

On March 7, 1965, Lewis and other civil rights leaders led more than 600 peaceful protesters across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala. to demonstrate the need for voting rights. They were met by Alabama state troopers, who brutally attacked them on what became known as “Bloody Sunday,” and Lewis nearly died of his injuries. The photos and videos captured that day, illustrating the cruelty of the segregated South, helped lead to the passage that year of the Voting Rights Act.

Over Lewis’s years of fighting for equal rights, he was arrested more than 40 times. When he died on July 17, he had represented Georgia’s 5th Congressional District for nearly 33 years.

“When I saw that face in person, he was very profound, yet simple,” Williams said. “He was a man of dignity. He was a representative of the way my older people taught me how to be as a young Black man. He was a symbol of that.”

At First Baptist, Williams recalled, Lewis talked about his lifelong fight for civil rights, the need to remain faithful to that fight, the importance of voting and making sure that young people continued the activism of his generation.

“I appreciate him for that day, and he could embrace you like you knew him for years and could talk to you like he knew you for years,” said Williams, who still has his copy of Lewis’s signed memoir.

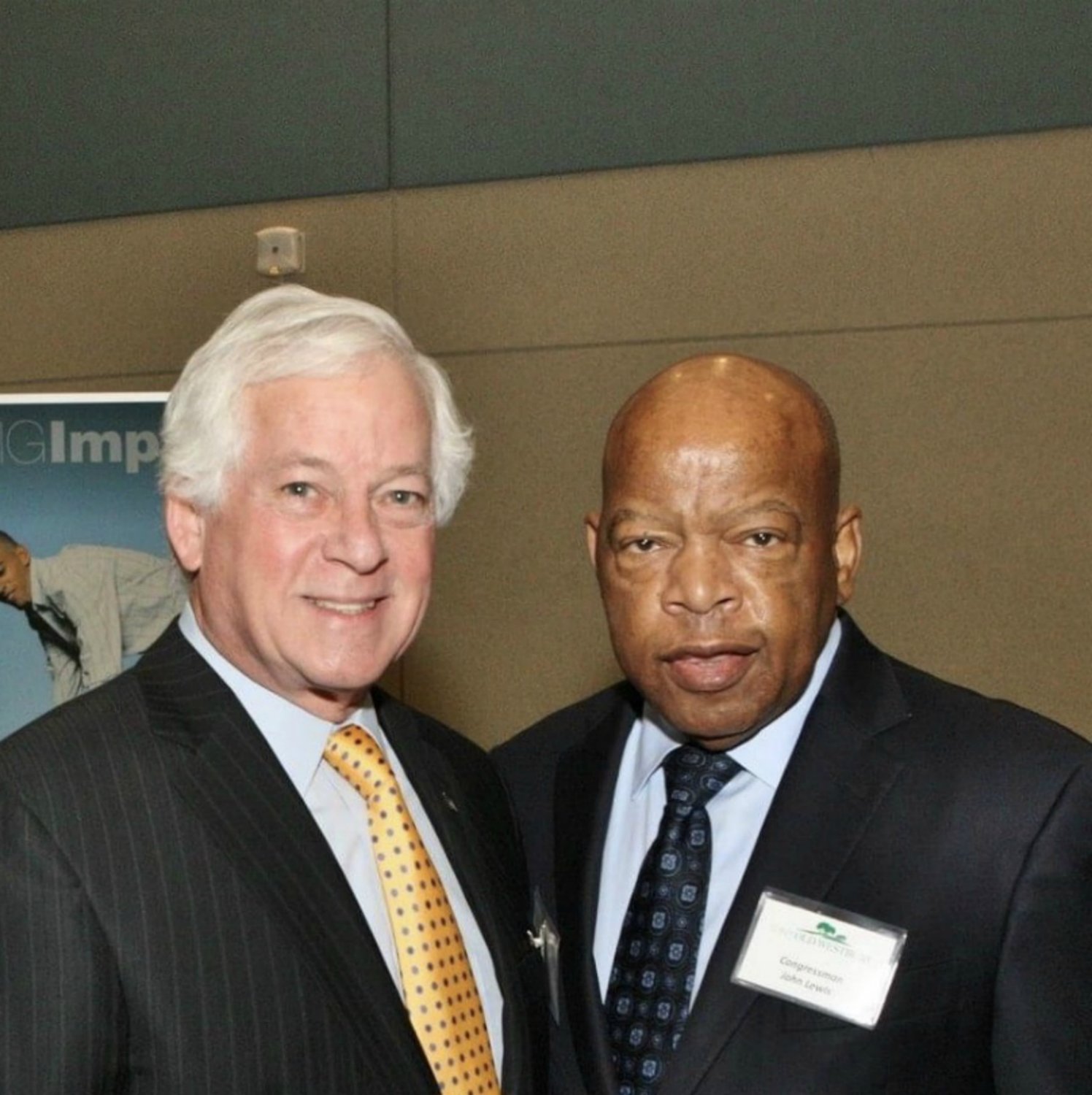

When the church attendees, who included Nassau County Legislator Delia Deriggi-Whitton and State Assemblyman Charles Lavine, approached him afterward to chat or pose for photos, Williams recalled, Lewis engaged every one.

Lavine met Lewis a second time in 2017, at an event at SUNY Old Westbury. Lavine said that his conversation with Lewis that day was one he will never forget.

“I had been a senior in high school in March 1965, at the time of Bloody Sunday,” Lavine said. “It was such a jarring, shocking occurrence that I would certainly never forget. It shaped my view of the world. I was then living in a small town in Wisconsin, and of course the seriousness of the civil rights movement was something that was pretty much oblivious to the town that I had been living in, while it was something extraordinarily compelling to me.”

As he grew up, Lavine said, he watched important moments in the civil rights movement on television, which had a lasting impact on him. At SUNY Old Westbury, “I got to share that with him,” Lavine said of Lewis. “He nodded and understood. He was a super-charismatic, heroic gentleman. So this is a meaningful recollection, and for what it’s worth, meeting him was certainly the highlight of my civic life.”

Lavine said that as a youngster, he never would have imagined he would someday have the chance to meet Lewis as a state assemblyman. Lewis’s life’s work, Lavine said, inspires him to protect the rights of his constituents.

“He grew up in a state where he could have gotten hung, but he became a U.S. Congressman in that same state [of Georgia],” Williams said of Lewis. “He did not forget the history that he had to go through to arrive where he was. I would hope his memory and legacy would motivate people to do a diligent study of our history, and [not] make some of the mistakes we have in the past. And it seems like we’re making some of those mistakes on the national scene.”