Remembering John Niven, one of the victims of 9/11

Died on Sept. 11, 2001, but was never found

Tim Lee was driving when he heard that the remains of his best friend, John Niven, had been identified. A senior vice president at the consulting firm Aon, Niven, 44, had perished on Sept. 11, 2001, in the south tower of the World Trade Center.

“I pulled over, had a lump in my throat and tears in my eyes,” Lee recounted, his voice wavering. “I kept seeing 911 a lot lately, in my bank statement, in my truck. When I see 911, I always take a moment in my day to think of John. He was a very, very dear friend. Such a special, caring, nice person.”

Niven’s remains, like those of over 1,103 other victims — 40 percent of the people who died in New York City that day, according to the chief medical examiner’s office — were never found. Until last month.

“They sent two police officers to my door just before Christmas to give me the news,” his widow, Ellen, said. “My heart sank. I thought something might have happened to my son. The police gave me a letter that said that John’s remains were found — very, very tiny bone fragments. I had no idea that anyone was still working on sifting through the debris of 911.”

John Niven was the 1,650th victim to be identified by the medical examiner’s office, through the utilization of next-generation DNA sequencing technology. The process, more sensitive than conventional DNA testing, is also faster.

“Next-generation sequencing takes roughly a day or two. Before, it took seven to eight years,” W. Richard McCombie, Davis Family professor of human genetics at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, said. “And the sample size can be lower. Much of the samples being analyzed from 911 are badly damaged, so that’s important.”

The first version of next-generation sequencing technology was used in 2007, and it has improved each year, McCombie added.

The medical examiner plans to continue using the technology. “Our solemn promise to find answers for families using the latest advances in science stands as strong today as in the immediate days after the World Trade Center attacks,” Chief Medical Examiner Dr. Jason Graham said. “This new identification attests to our agency’s unwavering commitment and the determination of our scientists.”

Ellen Niven gave DNA samples to the medical examiner’s office days after the attacks, hoping John’s remains would be found. Over the years, without an office dedicated to 9/11, she found it difficult to receive any additional information, she said.

Joseph Giaccone, who worked for Cantor Fitzgerald on the 92nd floor of the north tower, also died on Sept. 11. His remains have yet to be identified.

“I was the contact person for the M.E.’s office for the first three years, and they contacted me twice,” said Giaccone’s brother, James, who lives in Bayville. “But they were false alarms, a clerical error where they superimposed my brother’s number. They said they were sorry each time. Speaking for myself, after 23 years, I’m OK with them not finding anything.”

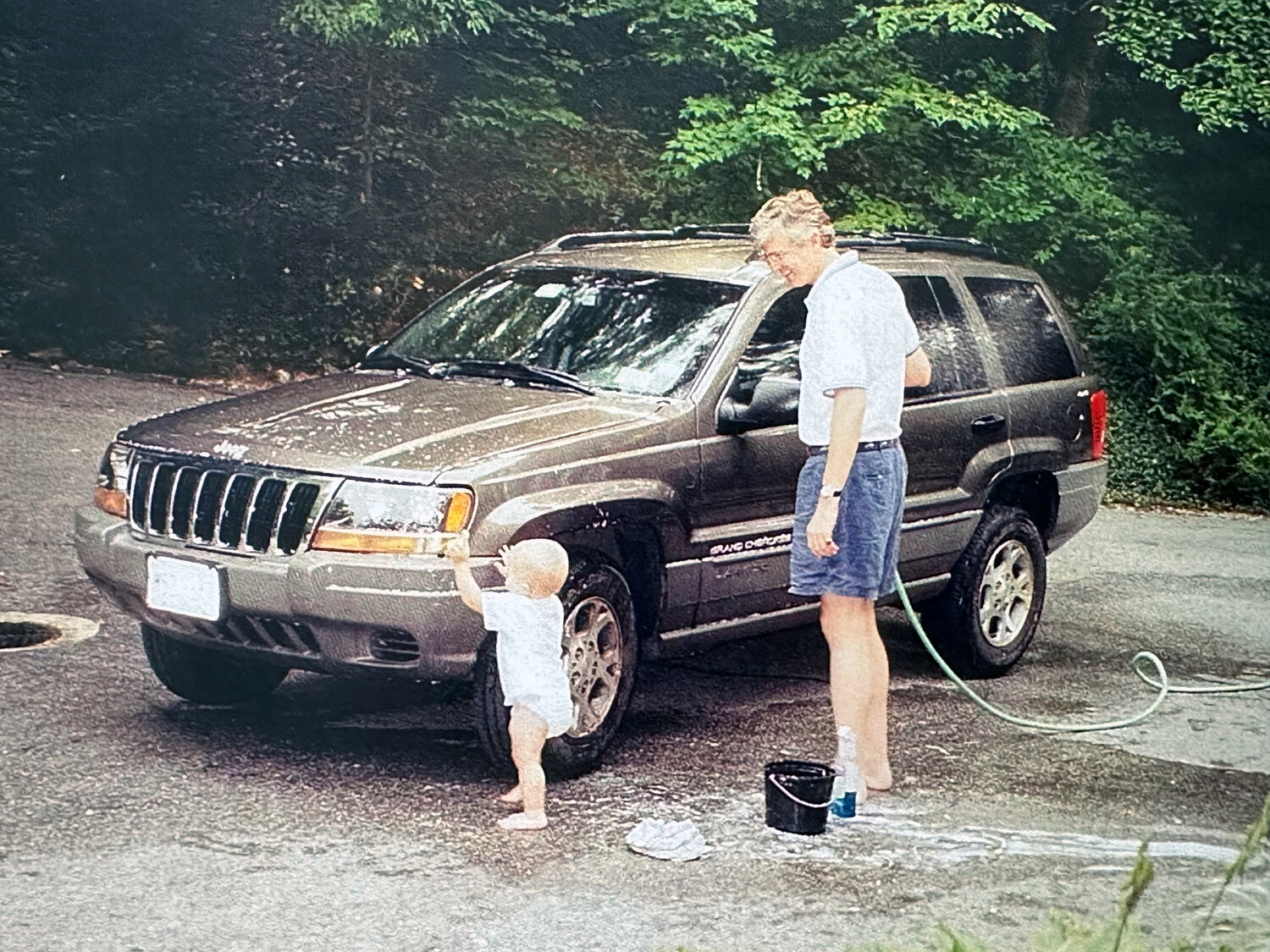

John Ballantine Niven was in the prime of his life in the summer of 2001. He was happily married to Ellen, whom he had wed in 1996, and they had an 18-month-old son, John Jr., whom he adored. He was successful at Aon, where he was an insurance broker, working with large companies across the globe.

Niven’s job required a great deal of travel, which, Ellen said, might have been the reason why, after the first plane struck the north tower, he returned to his office on the 105th floor of the south tower instead of joining his colleagues, who took an elevator down from the 70th floor and left the building.

“I heard that when they all got to the 70th floor, that Port Authority said it was safe, and that people could go back to their desks,” Ellen recalled. “I heard he went back upstairs to get his things because he was flying to Denver that day. The people who went down in the elevator got out. Those who went back upstairs were never heard from again.”

When Ellen received word in December that her husband’s remains had been identified, she was surprised by her reaction.

“We were all in such a heightened state of emotion,” she said. “I was sort of shocked. It’s not like you’re learning something new, but it’s incredible. The resources New York City is putting forth for this — I’m very grateful.”

Niven was born and raised in Oyster Bay Cove, in a house on Morris Lane, right next to Sagamore Hill, Theodore Roosevelt’s home. After they married, he and Ellen lived in an apartment on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, but they spent their weekends in Oyster Bay.

“We bought a gray-shingled old house on Morris Lane, and were always doing renovation projects on it,” Ellen said. “John liked to get out of the city on the weekends and do projects around the house, play tennis and see his group of childhood friends.”

Paul McNicol, who was born and raised in Cold Spring Harbor, met Niven when he was 6 years old. The boys played together during the summers, and became close friends.

“I think a lot about John,” said McNicol, who now lives in Mill Neck. “He was an extra-good friend, husband and parent. John was humble, open-minded and a very eligible bachelor before he married Ellen. Think Cary Grant with blond hair.”

Niven attended East Woods School with Tim Lee, who said they had played together since they “were in diapers.” Lee had a tree planted to remember Niven at their alma mater in 2001. “I researched trees and found one that flowered in September, the month he died, and I had a plaque put there,” Lee said. “We had a ceremony, and even though it was pouring rain, people came.”

Both boys went to boarding schools after East Woods: Niven enrolled at the Salisbury School and Lee at the Kent School, both in Connecticut. But they remained close, spending holidays and their summer vacations together.

Niven always enjoyed life, building go-karts and mini-bikes with Lee when they were boys, and becoming a skilled tennis player, competing for Lake Forest College, in Illinois, and later playing at the Piping Rock Club in Locust Valley.

But what Niven loved most was his toddler, John Jr., whom the family called “Jack.” He brought him everywhere, played with him and spoke of the child often.

“John was a really involved, doting father,” Ellen said. “He was thrilled to have a son. I think for anyone who loses a spouse, what you miss most is they don’t see your child grow up. They aren’t there for the milestones.”

And because there weren’t smartphones or social media in 2001, the victims, she said, are “frozen in time.”

“Jack wrote something once that the event that most affected his life was one he doesn’t remember,” Ellen said. “John’s friends stayed in touch with Jack. He knows John through the stories they’ve told him. It has given him a sense of who his father was.”

Niven was honored at a memorial service on Sept. 18, 2001, at St. John’s Episcopal Church, in Cold Spring Harbor, as well as a small gravesite service. Ellen buried a box of mementos. She does not intend to hold an additional service.

“I’m so blessed I have John’s child,” she said. “I’m thankful and I’m lucky. They’re similar. Jack looks quite like John, and acts quite like him, too. It’s really wonderful for me that I have that reminder of John in Jack.”

65.0°,

A Few Clouds

65.0°,

A Few Clouds