State testing is back to normal but not everyone is on board

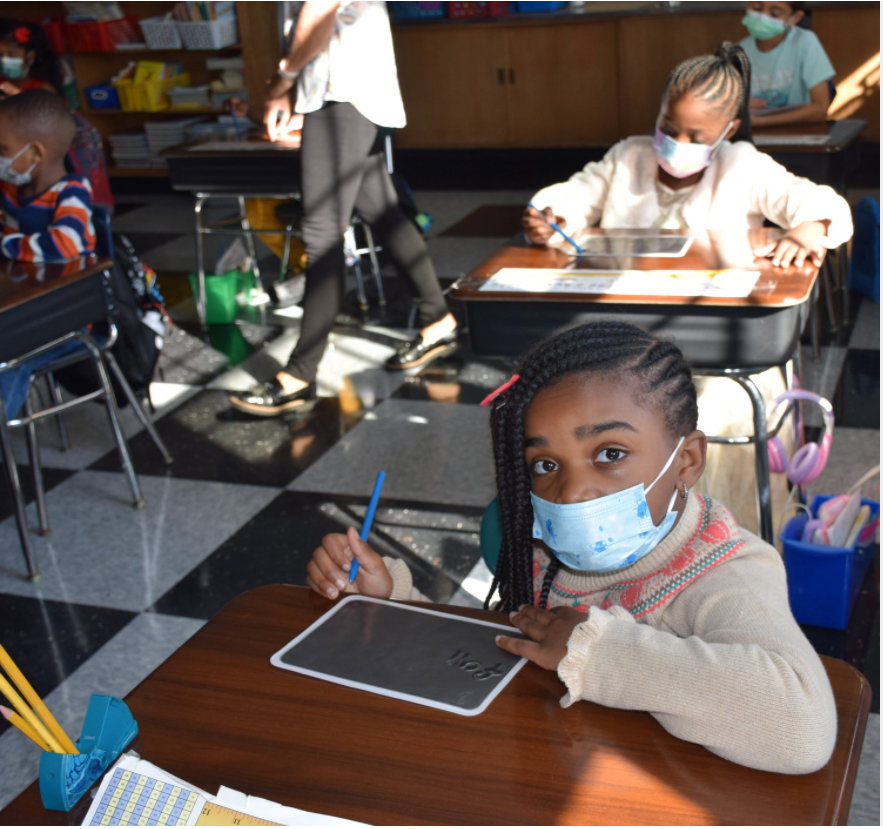

Students from grades three to eight dealt with the usual stress and jitters as they sat for the federally mandated English Language Arts state test last month. And the testing season is not over yet. Students are now gearing up for the math state test at the end of the month.

The state tests have returned in full after doing so in a scaled-back format last April following their cancellation in 2020 due to the coronavirus pandemic.

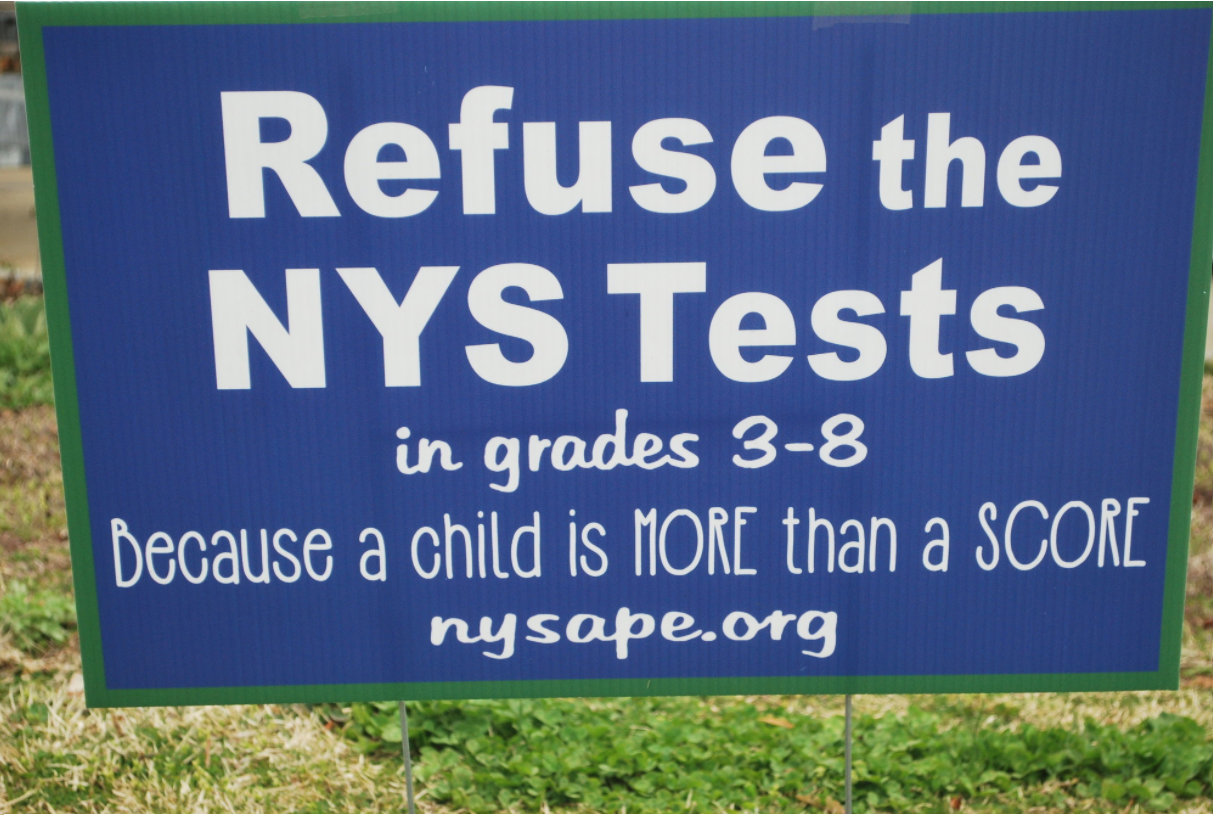

In the 2020-21 school year, roughly 4 out of 10 enrolled students took part in the assessments, according to state education officials. But as schools return to normal, resistance to the tests on the part of Long Island students, parents, teachers and even some school officials may have only intensified.

Parents and teachers took to the Long Island Opt-Out Movement Facebook page to rail against the “overtesting” of students who took this year’s ELA assessment, according to Jeanette Deutermann, a parent and a lead advocate of the Long Island Opt Out movement.

Deutermann said she had heard that Part One of the two-part test was “long but reasonable, and then Part Two was a disaster. The word I keep hearing was ‘brutal,’” she said, from teachers and parents.

While the test is not timed, teachers posted comments about proctoring sessions in which students went well beyond three hours, with children experiencing meltdowns and testing burnout as the exam dragged on, Deutermann said.

In Valley Stream, however, the testing sessions seem to have gone without a hitch, according to school officials. In District 30, students took under two hours, on average, to complete the first part of the exam, and under three hours for the second. In District 13, spokeswoman Grace Kwon said, “Every child was allowed to take the time they needed to take the test … There was no reason for students to feel rushed, stressed or under pressure. If certain students didn’t finish during the block of time, they were taken into another room and allowed to finish the test.”

The tests were originally intended to measure students’ ability to meet or exceed higher-learning standards adopted by the State Board of Regents in 2010, with the aim of assessing at least 95 percent of all students every year.

But according to Deutermann, evaluating student learning based on test-taking performance is a flawed educational strategy — one in which schools unduly prioritize tests in shaping curriculum. Good tests follow criteria that make them “diagnostic in nature…,” she said. “They don’t lead the classroom instruction. They are a result of classroom instruction … it’s like putting the cart before the horse.”

This message seems to be resonating across school districts. The prevailing view among administrators in Valley Stream schools is that statewide testing data offers limited insight into students’ academic progress, and that a variety of other evaluation methods in combination with state tests provide a more complete picture.

“The practice of Valley Stream 24 has always been to use a variety of assessment tools in evaluating student performance and growth,” Superintendent Dr. Don Sturz said. “These include authentic assessment methods, in-class participation, creating and using rubrics, assessing student performance in group activities, in-class testing, ability to understand and complete classroom and homework assignments, and performance on state standardized tests. No one method takes precedence over the others.”

District 13 “uses a variety of formative and summative assessments to monitor student learning and growth,” such as “project-based learning assessments along with local assessments from our ELA, math, science, and social studies programs,” said Superintendent Dr. Judith LaRocca. “Student data is used to identify individual strengths and areas for growth so that teachers can work to meet the needs of all learners in our district. State assessments are only one part of a student’s academic achievement and must be reviewed with other data to inform our important work with students.”

“As a district, we utilize many sources of data, including formative assessments as well as information gained from authentic tasks over the course of the school year, to develop our curriculum,” said district 30 superintendent Dr. Nicholas Sterling. “Additionally, through our hands-on learning approach, our administrators and teachers get to know our students and their individual strengths and areas in need of improvement. The state assessments represent only one source of data regarding students’ academic growth.”

The State Education Department appears to emphasize being sensitive to parents’ testing preferences for their children and catering to schools’ learning and resource needs in fulfilling state testing requirements. The department has affirmed that no school should fear losing out on federal aid or school improvement funds because of low test-taking rates. Even as an increasing number of parents decide to boycott state assessments, state officials have stated that schools will not be penalized as a result.

And thanks to parents’ pushback by way of the opt-out movement, Deutermann said, schools have been able to decouple state testing scores from teacher evaluations.

Nonetheless, consistently low test-taking rates still affect a school’s perceived academic reputation. “Schools still get ranked, sorted, labeled based on test scores,” Deutermann said. “You will have a handful of districts who are worried about their legacy.”

Have an opinion on this article? Send an email to jlasso@liherald.com