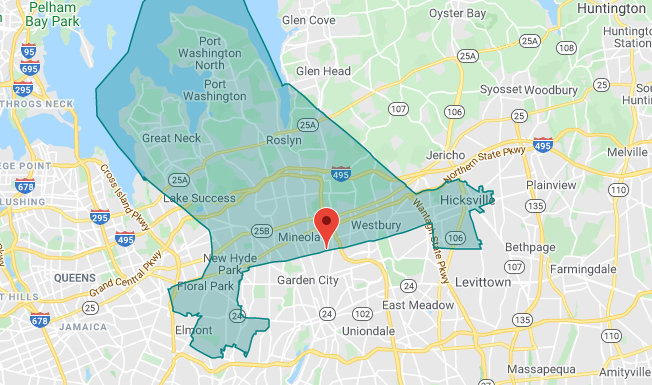

New state senate map to unite Elmont

No longer split between district 7, district 9

Under the new State Senate map approved by both houses of the Legislature and signed into law by Gov. Kathy Hochul earlier this month, Elmont will no longer be split between Senate Districts 7 and 9, but will fall almost entirely within District 7.

Mimi Pierre-Johnson, a community activist from Elmont, said this was a key change that she and others lobbied for through testimony before the state Independent Redistricting Commission. “We got 97 percent of what we wanted,” Pierre-Johnson said. She added, however, that, in her view, the new map still wasn’t perfect, because it left a few areas of Elmont — near the Southern State Parkway and Linden Boulevard — in the 9th District.

The new map, which will go into effect on Jan. 1, 2023, was created after the 2020 census. The statewide “blue wave” of Democratic victories in the 2018 midterm election cycle ensured that Democrats would be in charge of redistricting, which takes place every 10 years, following the census.

To Pierre-Johnson, keeping Elmont constituents together in one district makes more sense pragmatically, because it allows residents to garner political support more effectively for the funding of schools, public libraries and other local institutions. “From an activist point of view … it’s harder to get two elected officials together, agree and vote on the issues we fight on,” she said. “It’s beneficial to the constituents to keep them together.”

One such issue, according to Pierre-Johnson, is the children who live close to North Valley Stream, near Linden Boulevard, who attend Elmont Memorial High School. Providing transportation for those students, she said, is easier with most of Elmont contained within a single Senate district.

Pierre-Johnson said she believed politicians prioritize dividing up constituents in ways beneficial to them — a practice known as gerrymandering — over providing services to them.

“People feel disenfranchised by congressional lines,” State Assemblywoman Michaelle Solages, a Democrat from Elmont, said in a previous Herald story. The Assembly has been controlled by Democrats for decades, and Solages’s district remained untouched by the new map.

“We should have nice, clean districts that people don’t need a ruler or rubric for to see how the lines have been drawn,” said Solages, whose district was created in 2012, after the 2010 census, in the same process that split Elmont at the Senate level.

“We want to make sure that the process is that the people are electing their officials,” she added, “not that elected officials are choosing their voters.”

“If we didn’t fight and go before the redistricting committee and build a statewide coalition, what happened to Elmont 10 years ago would have happened again,” Pierre-Johnson said, referring to the separation of Districts 7 and 9 in 2012.

She said she would now focus on the next step of the redistricting process, at the municipal level. “Now that the state is done, the next step is local,” she said, adding that Elmont is affected by the makeup of both the Nassau County Legislature and the government of the Town of Hempstead. Town government is particularly relevant to Elmont residents, Pierre-Johnson said, because the town controls parking issues at the UBS Arena.

A major feature of the new state map is that Long Island’s nine State Senate districts no longer all have majorities of white residents. As a result of the redistricting, two districts will contain more minority voters than white voters. Pierre-Johnson said that is evidence that the demographics of the Island have changed, and its population is now more diverse. “The census proved that Long Island is changing,” she said.

Indeed, the 2020 census found that over the past decade, Long Island’s minority population increased by nearly 290,000, while its white population decreased by nearly 200,000.

Pierre-Johnson shot down what she described as tropes about Black and Latino Americans “destroying” Long Island. “If we have fair maps, everyone wins,” she said, adding that just because an area is predominantly “Black or Brown” doesn’t mean that only people of color should live there.

“It should be a good diverse district,” she said, adding that this is what she has fought for, and what the new map represents. “If everyone lives together, we all could win,” Pierre-Johnson said.

Republicans have voiced their criticism of the new district map, accusing Democrats of using their majority in the State Legislature to carve up blocs of voters into reliable districts in which they will be re-elected each cycle. Democrats have countered that they are rolling back decades of similar gerrymandering implemented by Republican majorities in the Legislature.

Pierre-Johnson agreed with the latter sentiment, saying that past maps have divided communities in half for the advantage of political incumbents. Her neighbor across the road, on Crystal Street, is in District 7, she said, while her own house is in District 9.

While she conceded that both political parties gerrymander districts, she expressed hope for fair boundary drawing by both parties in the future. “The hope is that whichever party comes to power next, they continue that trend, so we can have fair maps that reflect the community,” Pierre-Johnson said, “rather than maps that hold politicians in office.”