Malverne Civil War veteran remembered

This Veterans Day, one of Malverne’s own who was a Civil War veteran is receiving the recognition he deserves — nearly a century after his death.

Members of Moses A. Baldwin Camp No. 544, a local chapter of the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War, gathered at Greenfield Cemetery in Uniondale on Oct. 15 to dedicate new headstones to four veterans of the Civil War who are buried there. The ceremony was part of an ongoing project to locate the resting places of veterans of the Union Army.

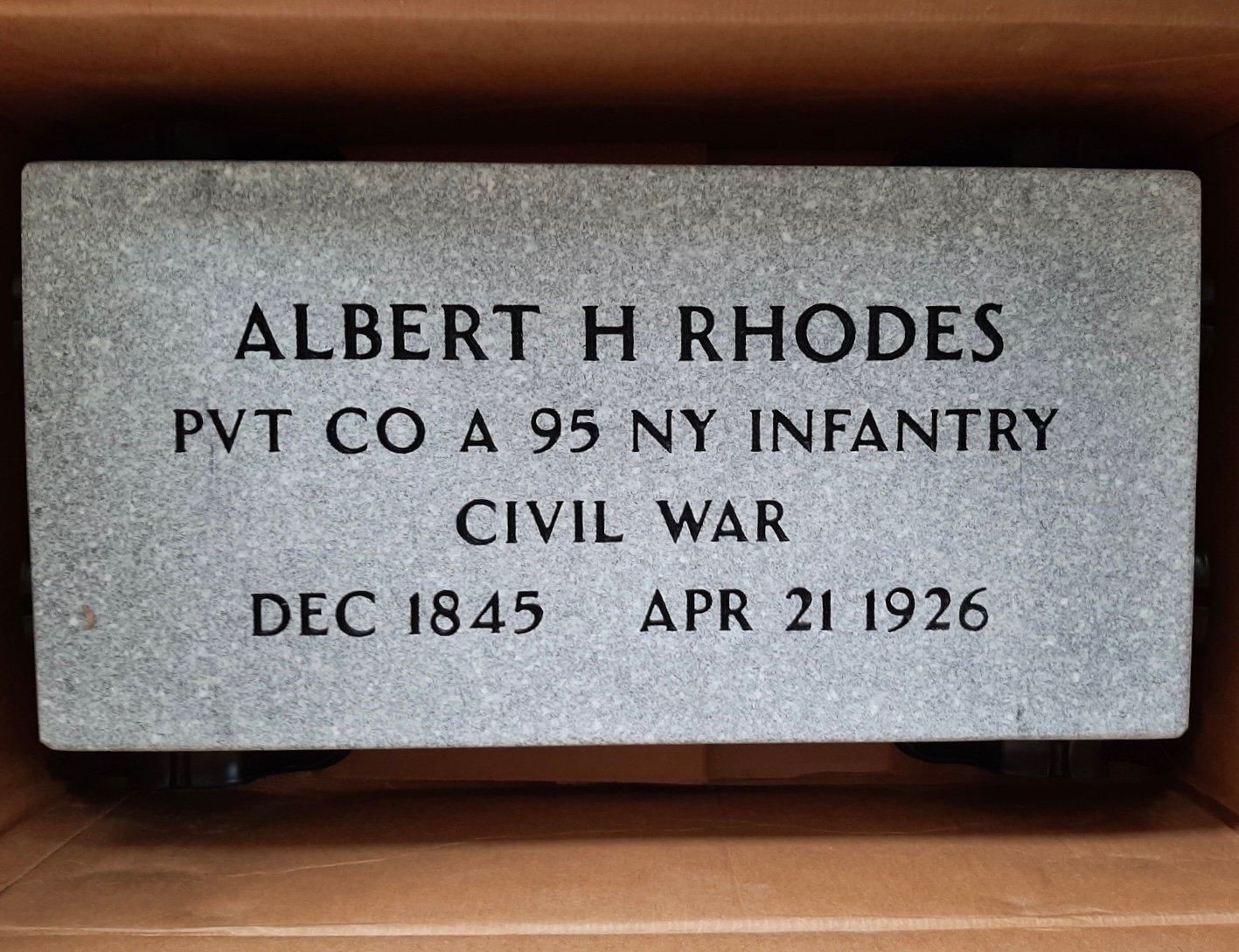

One of the Civil War veterans buried at Greenfield Cemetery is Albert Henry Rhodes, who lived in what is now Malverne.

Dennis Duffy, camp secretary and graves registration officer, explained the activities of his camp and the process of locating the unmarked graves.

“In a nutshell, our mission is to remember the boys in blue, those who fought to save the Union and abolish slavery,” Duffy said. “One of the things we do is to try to locate unmarked graves of Civil War veterans and then obtain a headstone for the grave from the Veterans Administration.”

The details of Rhodes’s life are sparse, but create a rough road map of the experiences of a Union soldier at the time.

Rhodes was born in December of 1843, according to records from the New York State Military Museum, but his exact date of birth is unknown. His surname was also spelled “Rhoades,” because record-keeping was not standardized at the time.

At the Nov. 2 meeting of the Malverne board of trustees, village Historian Dave Weinstein offered some insight into the veteran and the community he was born into.

“This is something that probably most people don’t realize that the government does,” Weinstein said. “Secondly, the people and Malverne can say, ‘Hey, here is a guy that was born in the village, served in the Civil War, was remembered.’”

Weinstein added that at the time Rhodes was born, Malverne was little more than a hamlet of farmhouses known as Norwood.

On Jan. 17, 1862, the then 19-year-old Rhodes enlisted as a private in the 95th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment. He probably would have enlisted at the Union Army’s recruiting office in Manhattan’s City Hall Park — which was a ramshackled construction area covered in large advertisements boasting of generous wages for those who took up arms. At that time, there were no bridges over the East River, and Rhodes likely got to the recruitment station by ferry.

He willingly volunteered, since the Militia Act of 1862, enabling states to draft people into service, would not be passed until July of that year.

The 95th Infantry was officially organized under the command of Col. George H. Biddle on March 6, 1862, to serve for a term of three years. On March 18, Rhodes’s company was mustered out of Fort Columbus — now called Fort Jay — on Governor’s Island and sent to Washington, D.C.

For a short time, the 95th Infantry served in the garrison of the nation’s capital before being deployed in the campaigns against the Confederacy in Virginia.

The 95th would see action in many of the Civil War’s most well known and decisive battles, including the second battle of Bull Run, the battles at Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, the Battle of the Wilderness, and the final Appomattox Campaign, at which the bulk of Confederate forces surrendered.

While it is difficult to know whether any individual infantryman fought in a battle, Duffy said that companies were rarely separated from their regiments, and that Rhodes was almost certainly in most, if not all, of the battles that involved the 95th Infantry.

There is little information about Rhodes’s life after the war. The 1920 census lists him as married to a woman named Catherine. According to Ancestry.com, he fathered a son, William E. Rhodes, who was born in 1890, though the site offers no further information on William.

Rhodes died on April 21, 1926, at age 82, and he was buried at Greenfield Cemetery in Uniondale. His grave was unmarked, even though he would have been entitled to a government-issued headstone.

“Maybe his family didn’t know, or no one cared, or at the time no one could come up with the necessary documentation,” Duffy said.

The cemetery did, however, make note of Rhodes’s veteran status at the time of his interment, which helped researchers find him nearly a century later.

“These graves, most of them, marked whether they were a veteran or not, which is very unusual,” Duffy said. “Cemeteries didn’t usually do that. We looked at the cemetery record, and it was stamped ‘GAR.’”

The “GAR” designation stands for the Grand Army of the Republic, the veterans group that preceded the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War.

Rhodes, three other Civil War veterans, a veteran of the Spanish-American War and a veteran of World War I, all buried in Greenfield Cemetery, received headstones commissioned by the VA and installed by the Town of Hempstead.

The Sons of Union Veterans, some dressed in period uniforms, conducted a service that borrowed from traditional military funerals of that era.